image: FN

Ever wonder how, exactly, counterfeit goods make their way into the U.S. from China – where the vast majority of counterfeit goods are made? Well, a new lawsuit initiated by the United States Department of Homeland Security – which centers on New York resident Su Ming Ling’s “sophisticated scheme” to import roughly $250 million in fake brand-name apparel and footwear – provides a glimpse into how it works.

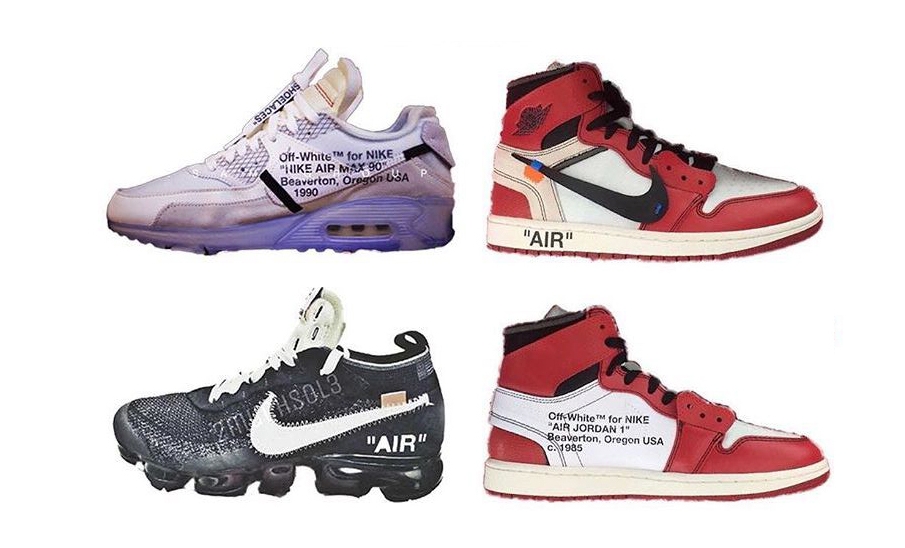

Mr. Ling, 50, was arrested in California last week when he attempted to flee the country by way of a flight from San Francisco to Taiwan. His arrest comes on the heels of the seizure of hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of counterfeit clothes and shoes – including fake Nike sneakers, Ugg boots, and True Religion jeans and other apparel – by U.S. Customs and Border Protection and a several-year-long investigation by Homeland Security.

“Using a combination of internet savvy and old-fashioned counterfeit distribution techniques, Ling perpetrated a lucrative counterfeiting scheme involving fake name-brand items,” Bridget Rohde, acting United States attorney for the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York, said in a statement.

A 3-Year-Long Investigation

According to Homeland Security’s lawsuit, which was filed in the Eastern District of New York on August 31, Ling – with the help of others – “knowingly and intentionally conspired to traffic in goods, [including] sneakers, boots, athletic jerseys, jeans, and [other] apparel, knowingly using counterfeit marks,” and did, in fact, “knowingly, intentionally and fraudulently import” such goods.

Specifically, Ling arranged for the fake goods to be “smuggled into the U.S. from China through New Jersey Ports for delivery to wholesalers of counterfeit goods in, among other places, Brooklyn and Queens, New York.” Homeland Security asserts that “in furtherance of this conspiracy, Ling registered Internet domain names resembling the Internet domain names of real import businesses and used email addresses associated with the misleading domain names to fraudulently portray himself as a representative of [various] real import businesses.”

For example, Homeland Security alleges that on a number of occasions, Ling’s shipments from China were assigned to ‘MaxLite SK America Inc.’” and its representative, Anthony Huang. In its investigation of Ling’s operations, Homeland Security “identified a real company named MaxLite, Inc., which had previously been named SK America, at the same address in West Caldwell, New Jersey listed on the commercial invoices and packing lists” for Ling’s imports.

According to the lawsuit, “A representative of MaxLite, Inc. advised a [Homeland Security] agent that it had never used the Internet domain names [listed on Ling’s import documentation],” that it never imported any goods for Ling, and that an individual named Anthony Huang had never been employed by the company.

Upon seizing two of Ling’s iPhones, government officials found that in addition to controlling numerous fraudulent domain names and email addresses, for the purpose of communicating with others in furtherance of the conspiracy to smuggle counterfeit goods into the U.S., Ling had saved “two photographs of a computer screen displaying the website used by the real MaxLite, Inc., demonstrating that the [he] had researched the address and location of the real import business to pose as a representative of the business in furtherance of his scheme to fraudulently import of counterfeit goods.”

Additionally, Ling “provided customs brokers with false documentation for shipping containers filled with counterfeit goods carried on merchant vessels arriving at New Jersey Ports.” Homeland Security had been investigating Ling’s activities since 2014, when its agents first uncovered a shipment of approximately “29,500 pairs of counterfeit [Nike] sneakers which, if marketed as genuine, would have had a manufacturer’s suggested retail price of approximately $1.5 million.”

Ling had “misrepresented the true contents and value of the cargo in the shipping containers,” stating, on that specific occasion, that the contents of a container consisted of “bottle openers, keychains and frames with a dutiable value of approximately $41,436.” In reality, as discovered by Homeland Security investigators and Customs and Border Patrol agents, the shipping container also contained almost 30,000 pairs of counterfeit Nike-brand Air Force 1 sneakers.

And that was just one of the “approximately 200 forty-foot-long shipping containers that Ling and his co-conspirators fraudulently imported into the United States between approximately May 2013 and January 2017 using stolen business identities and falsified shipping documents.”

As of the time of filing, Homeland Security estimates that “the intended economic loss to the holders of trademarks as a result of [Ling’s] conduct is approximately $250 million.” Ling is currently facing 20 years in prison in connection with the scheme.

Nike’s Efforts to Fight Fakes

While Nike would not comment on whether it was involved in Homeland Security’s investigation of Ling and his scheme, a significant portion of which centered on the importation and sale of counterfeit Nike sneakers, a spokesman for the Portland, Orgeon-based sportswear giant did tell TFL: “Nike aggressively protects our brand, our retailers, and most importantly our consumers against counterfeiting. We actively work with law enforcement and customs officials around the world to combat the production and sale of counterfeit products.”

As reported by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (“OECD”) last year, international trade of counterfeit goods represented upwards of 2.5 percent of overall world trade, or $461 billion, in 2013. That report, entitled “Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Mapping the Economic Impact,” which OECD called the most rigorous to date, was based on roughly half a million customs seizures around the world between 2010 and 2013. Released in April 2016, the report found that Rolex, Ray Ban, Louis Vuitton, and of course, Nike, are brands that “seem to be more intensely targeted by counterfeiters,” according to the report.

OECD’s findings corroborate a previous World Customs Organization report that identified Nike as the most frequently counterfeited brand in 2013.

The bust of Mr. Ling and his operation comes less than a year after customs officials in Iquique, Chile seized $31 million in fake Nike and adidas sneakers.