Nike and StockX, and Quentin Tarantino and Miramax are not the only parties currently embroiled in legal squabbles over non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”). In fact, late last month, Tamarind Art filed a breach of contract and declaratory judgment lawsuit, accusing the administrators of Maqbool Fida Husain’s estate (“MFH Estate”) of standing in the way of its launch of a series of NFTs related to Husian’s “Lightning” painting that Tamarind acquired in 2002. Despite holding “the exclusive, worldwide, royalty-free license to reproduce [the artwork] in any format, including digital formats,” Tamarind claims that it received a cease-and-desist letter from the MFH Estate, accusing it of copyright infringement, and demanding that it immediately halt its plans to release NFTs and its corresponding marketing campaign.

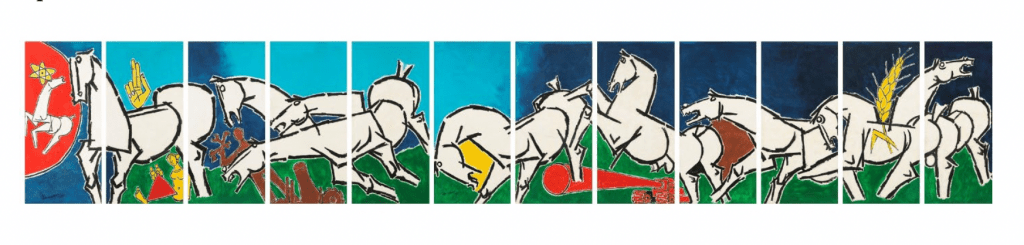

According to the complaint that it filed on January 21 in a New York federal court, New York City-based Tamarind claims that it acquired the Lightning painting from Husain in 2002 for $400,000. As part of the purchase, the art collector/gallery alleges that Husain granted it “an exclusive, royalty free, worldwide license to display, market, reproduce and resell all or any part of the artwork,” including “on all digital and off-line media.” Beyond that, Tamarind asserts that in furtherance if its acquisition of the 60-foot-long mural, which consists of twelve massive panels, Husain also offered up a rare term for the deal: a total grant of all ownership and intellectual property rights associated with the painting.

In other words, Tamarind says that Husein “agreed that he [would] no longer [be] the owner of the artwork or the intellectual property associated with it” if it was purchased by Tamarind.

(For some context: Tamarind claims that in November 2002, following months of negotiations between Husain and Tamarind principal Kent Charugundla, and in an attempt to “sweeten the deal” after Charugundla pushed back on the $400,000 price tag, Husain offered to grant Tamarind “all rights [in] the Lightning painting” in order to enable Tamarind “to print posters or graphics or any digital works, or anything Tamarind wanted to do with the work to help [Tamarind] get some money back.” At the same time, Tamarind alleges that Husain “also promised that Tamarind would ‘make money back on making digital copies and graphics over your lifetime and for your generation.’”)

The parties ultimately closed the deal in December 2002, and Tamarind not only took physical possession of the painting, but Husain formally granted it “an exclusive, royalty free, worldwide license to display, market, reproduce and resell all or any part of the artwork, including all intellectual property in respect thereof.” The license further gave Tamarind the “absolute and royalty free right to sub-license the artwork to any third party,” while also explicitly stating that “images of the artwork may be reproduced by the buyer on all digital and offline media.”

In a follow up agreement in April 2003, Tamarind claims that Husain signed off on a provision that stated that he “shall have no rights on/in the images or works, artworks, created for, and/or those purchased by Tamarind/affiliates,” thereby, serving to “extinguish any residual rights [Husain] could have had in the artwork.”

Tamarind states that it maintained a relationship with Husain until he died in 2011, with the artist visiting the Tamarind gallery in New York, painting additional works for Tamarind, and participating in Tamarind events. All the while, he “never once complained or objected to Tamarind’s use, display or reproduction of the [Lightning] artwork from the time Tamarind acquired it in 2002 until his passing.” In fact, Tamarind contends that it “displayed the artwork continuously in one form or another from 2002 until today,” including in books that it offered up for sale, “without objection” from Husain.

Fast forward to early this year, and Tamarind launched a project called LightningNFT, in furtherance of which it “intends to ‘drop’ an undetermined number of NFTs with 62 unique traits,” and each of which “will represent one of the artwork’s 12 panels with its own trait.”

Shortly after the initial marketing of the LightningNFT project, Tamarind claims that it received a cease-and-desist letter from the MFH Estate. In the letter, the Estate admitted that “Charugundla owns the original artwork,” but argued that he has “no right to ‘right to reproduce it, distribute copies, create derivative works based on it or display it publicly,’” including in connection with the NFTs. Declaring that the NFT Project would violate “multiple provisions of the Copyright Act,” the MFH Estate demanded that Tamarind “immediately cease operations [of the NFT project], cease any marketing efforts related to the NFT Project, and cancel all pre-sales.”

With the foregoing in mind, Tamarind filed suit, seeking a declaration from the court that it is within its rights to proceed with the NFT project and that the NFT project “does not infringe on any of the Estate’s supposed intellectual property rights in the artwork.” In addition to its non-infringement and ownership declaratory judgment claims, Tamarind sets out a claim of Breach of the Implied Covenant of Good Faith and Fair Dealing, accusing the MFH Estate of breaching the covenant of good faith and fair dealing “by interfering with the NFT project without basis and in bad faith – simply to destroy the benefit of the parties’ bargains and prevent the launch of the NFT project.”

Aside from declarations from the court, Tamarind has also asked the court to award it monetary damages in an amount to be proven at trial.

The Tamarind case is one of the latest lawsuits to come out of the budding field of NFTs. It follows closely from trademark infringement case that Nike filed against StockX on February 3 over the latter’s offering of “unauthorized” NFTs. Before that, Miramax filed a lawsuit against Quentin Tarantino in November after the director “announced plans to auction off seven ‘exclusive scenes’ from the 1994 motion picture Pulp Fiction in the form of NFTs.” Still yet, in a July 2021 securities class action lawsuit that an individual named Jeeun Friel filed against Dapper Labs Inc., he alleged that the defendant’s NBA Top Shot platform actually sold securities when it offered up NBA-centric NFTs, and ran afoul of U.S. securities laws in the process, as the NFTs were not registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Still yet, the question of who has the right to sell NFTs tied to existing assets is at the heart of another headline-making lawsuit, one that Roc-A-Fella Records filed against Damon Dash in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in June in a quest to prevent the Roc-A-Fella Records co-founder from auctioning off an NFT tied to the copyright for Jay-Z’s debut album, Reasonable Doubt.

The case is TAMARINDART, LLC v. Raisa Husain and Owais Husain as Administrators of the Estate of Maqbool Fida Husain, 1:22-cv-00595 (S.D.N.Y.).