New Balance is fighting to keep the trademark infringement and dilution case that it is waging against Golden Goose in place, arguing that Golden Goose’s motion to dismiss the claims waged against it this summer in connection with its lookalike “Dad-Star” sneaker is “a procedurally premature attempt to litigate the merits of a case that has barely begun.” In particular, New Balance asserts in its December 12 opposition to Golden Goose’s motion to dismiss that despite the Italian sneaker-maker’s claims to the contrary, it has sufficiently defined its 990 sneaker trade dress, and has alleged that its trade dress is non-functional and has developed secondary meaning.

Setting the stage in its opposition filing, which it lodged with the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts (as first reported by TFL), New Balance alleges that Golden Goose – which is known for its $500-plus Italian handcrafted sneakers – “makes three main arguments that each ignore the governing standard and the substance of New Balance’s well-pleaded allegations” …

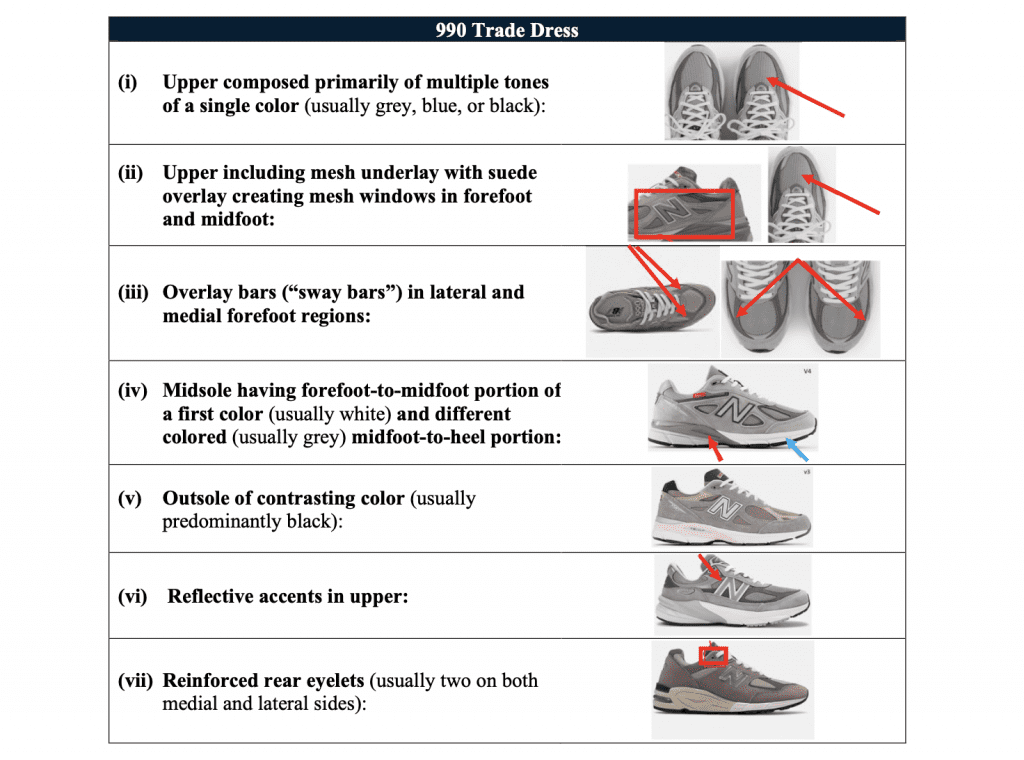

– First, Golden Goose “asserts that New Balance has not identified its trade dress with specificity. To the contrary, New Balance described the distinctive features of its claimed dress in detail using both a narrative description and annotated images. This level of detail is more than adequate to survive a motion to dismiss.”

– Second, Golden Goose “argues that New Balance insufficiently plead that its trade dress has acquired secondary meaning. New Balance has more than adequately plead secondary meaning [by] pleading numerous individual factual allegations on every element of the legal test even though evidence of each is unnecessary at this stage.” For example, New Balance says that it “plead specific facts demonstrating its sales (millions of shoes, representing hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue), the length, scope, and nature of its advertising (over twenty years of advertisements touting the design through a variety of marketing channels making millions of consumer impressions), and the presence of extensive unsolicited media coverage acknowledging its iconic design.”

Beyond that, it “provided facts evidencing that consumers recognize the existence of a single 990 Trade Dress and exclusively associate that trade dress with New Balance, because they recognize that Golden Goose has stolen it: ‘Golden Goose basicallystole the New Balance 990 silhouette bar for bar;’ ‘I had no idea Golden Goose had fake NB 990s;’ ‘My Golden goose’s [sic] look like New Balance;’ ‘990, but make it Golden Goose.’” (Emphasis courtesy of New Balance.)

– Third, Golden Goose “contends that New Balance did not adequately allege that its trade dress is non-functional.” However, New Balance argues that it “expressly made that allegation importantly, Golden Goose’s argument improperly relies on the suggestion that certain individual attributes may be functional, which is legally irrelevant.” The proper test, according to New Balance, is “whether the claimed elements are functional in combination. They are not. The trade dress serves one primary purpose: to identify New Balance as source.”

Because it has identified its trade dress “with specificity and adequately plead both secondary meaning and non-functionality,” New Balance urges the court to deny Golden Goose’s motion, and “in the event that the court agrees that certain claims need to be plead with greater particularity,” New Balance argues that the court should grant it leave to amend its complaint rather than dismiss the case in its entirely.

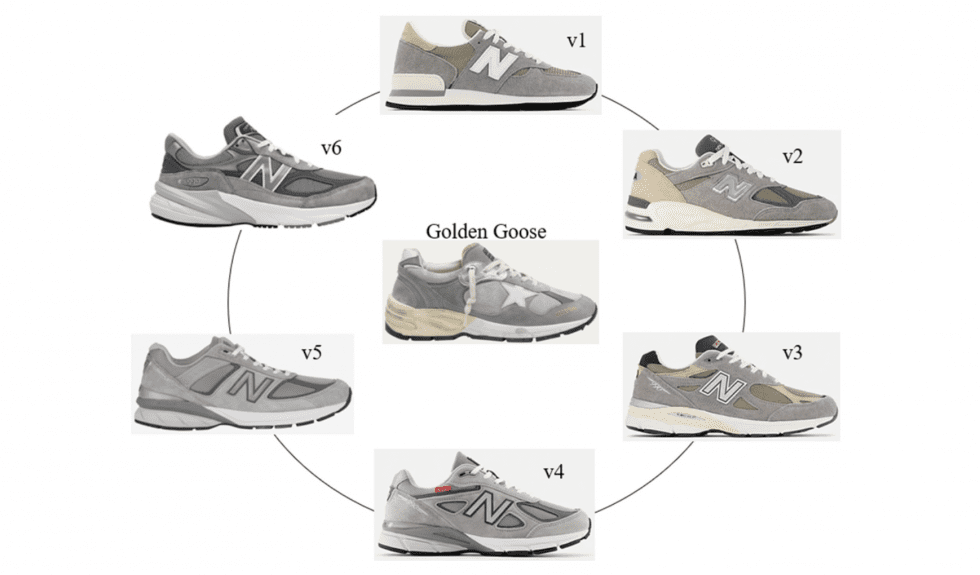

New Balance’s filing comes on the heels of Golden Goose arguing that the plaintiff sneaker-maker’s complaint should be tossed out on the basis that New Balance fails to plausibly allege that it owns a protectable trade dress in the hot-selling collection of 990 sneakers. New Balance falls short here, per Golden Goose, because there is no such thing as a single 990 design. While “there may be a line of shoes that New Balance sold under the 990 designation for the past forty years,” Golden Goose claims that “New Balance itself admits that this particular model has been redesigned six times in forty years.” And “as the images provided in the complaint make clear, these re-designs have resulted in a 990 shoe that is not consistent in appearance or features.”

In addition to failing to offer “a precise expression” of the alleged trade dress at issue, Golden Goose has argued that New Balance also fails to allege two foundational elements: that the alleged trade dress has acquired secondary meaning and that it is non-functional.

THE BIGGER PICTURE: Underway behind the scenes of the legal clash is a reported effort by Permira-owned Golden Goose to expand beyond its core offering of expensive, worn-in-looking sneakers. Italian luxury sneaker brand Golden Goose reported a 30 percent increase in revenues last year to 501 million euros and “sees scope for further growth by expanding beyond its core product range,” Chief Executive Silvio Campara told Reuters this fall. “We will keep on innovating our business, which is sneakers, but there will be something out of sneakers that is ready to be launched on the market,” Campara said.

That expansion is expected to be fueled by the cash that the Milan-based sneaker company is reportedly looking to raise in an initial public offering in Italy next year. Sources close to the matter said recently that Golden Goose is looking to raise about 1 billion euros ($1.1 billion) and that its majority owner, Permira, has “enlisted seven banks to underwrite what is set to be one of Europe’s biggest IPOs” in 2024.

The case is New Balance Athletics, Inc. v. Golden Goose USA, Inc., 1:23-cv-11898 (D.Mass.).