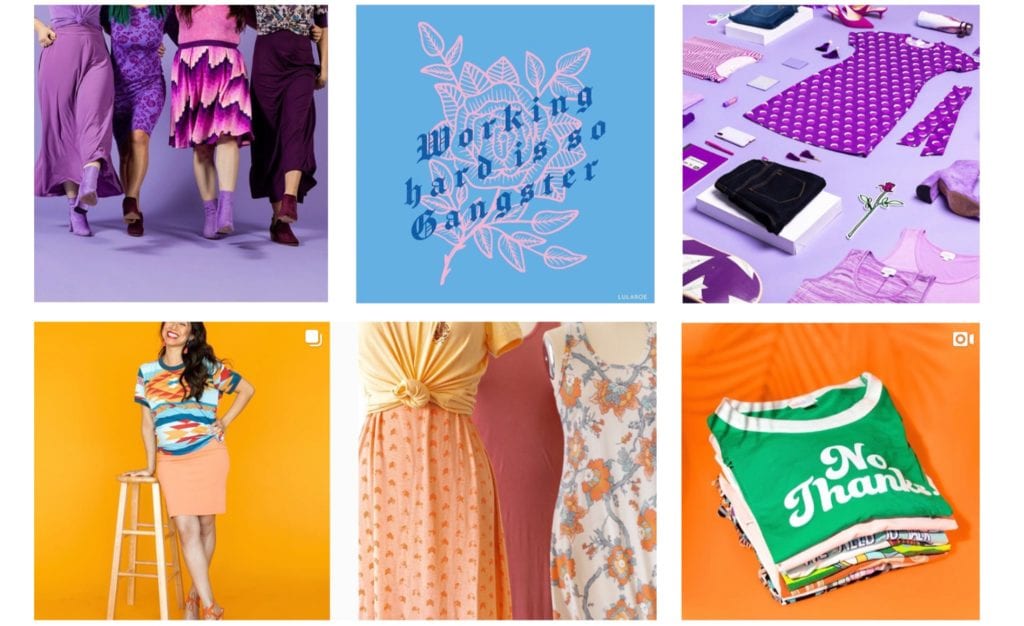

LuLaRoe holds itself out as “a champion of women seeking financial freedom” by enabling them to work from home, be their own boss, and make money – potentially a whole lot of it – by selling leggings and other casual clothing. That is what four former LuLaRoe representatives have said of the 7-year old multi-level marketing (“MLM”) company. But the reality is far from the financial freedom and the make-your-own-hours lifestyle that LuLaRoe peddles. In reality, while the Southern California-based company has built a $2 billion business, many women in its web have suffered, and the result if a growing rumble of discontent.

Founded in 2012 by Mark and DeAnne Stidham, LuLaRoe joins a large pool of companies that have enlisted over 20 million individuals across the country – nearly 75 percent of whom are women, according to the U.S. Direct Selling Association – to sell everything from yoga pants and printed dresses to cosmetics and essential oils. It is a classic MLM operation, one in which a company operates by selling products through a network of distributors.

MLMs, which currently amount to a $36 billon industry in the U.S., work like this: individual distributors – or as LuLaRue calls them, “consultants” – buy a certain (often pre-determined and required) amount of the company’s product at wholesale and then sell it, entitling them to a cut of the profits. The potential for earning is not limited to selling, though. It can also come from an existing member recruiting new distributors – if someone signs up under you, you become their “upline” and receive a commission from their earnings, too. If your recruits sign up anyone beneath them, you also take a cut of their profits, and so on.

The difference between an MLM and an pyramid scheme is that there is a product at play when it comes to MLMs. While pyramid schemes –which are illegal – see participants make money solely for recruiting new participants, enlist members in order to actually sell products. For LuLaRoe, those products are leggings and other women’s apparel. For Rodan + Fields and Younique, it’s skincare and beauty goods. Monat’s product is hair products, and Young Living’s offerings are essential oils.

But while product is one of the key distinguishing factors between illegal pyramid scheme and MLMs, critics say that many MLMs have a business model that focuses on recruiting “downline” and getting new distributors to buy the product, rather than on actual sales to consumers, making them akin to pyramid schemes.

This is furthered by the fact that many MLM models come with a high cost of entry. Others routinely see individual distributors build up inventory they cannot sell, and yet, require them to buy more product on a regular basis in order to continue to participate. (The latter may be in direct violation of the Federal Trade Commission’s 70/30 rule, which requires that MLM sellers must sell more than 70 percent of their individual monthly inventory before being required to purchase additional products in order to be eligible to earn commissions).

A recent report from The Guardian revealed the “cultish grip” that some of these MLM companies have on many of their recruits. They offer people a life-changing financial opportunity, but many lose money when they sign up to MLMs. Only the few at the top of the pyramid profit. A recent study from the AARP revealed that only one quarter of the MLM participants surveyed had made a profit. The Washington Post cited a separate study, which found that nearly 60 percent of the 1,049 MLM participants, who were surveyed, had earned less than $500 from their MLM participation over the past five years. The remaining 40 percent either did not make a profit or lost money.

With such dismal numbers in mind, it is not surprising that there is a mounting anti-MLM movement, which includes everything from heavily-followed online forums and true-life documentaries to big-money class action lawsuits, such as those that have been filed against LuLaRoe. For instance, Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson announced in January that his office had filed suit against LuLaRoe in state court for allegedly “misrepresenting and failing to honor its refund policies in violation of the state Consumer Protection Act.”

Renewed media attention and a burgeoning grassroots movement against MLMs means that many of these companies are taken to task. While LuLaRoe is proving to be one of the most headline-making companies in the space, because it is a magnet for multi-million dollar lawsuits, it is not alone. This spring, Young Living, the $1.5 billion essential oils giant, was sued for allegedly running an illegal pyramid scheme. Shortly thereafter, it was revealed that diet and nutritional supplement maker Advocate had become a target of Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) scrutiny. Abandoning its MLM model in light of a confidential settlement with the FTC, Texas-based AdvoCare announced in July that the consumer protection agency had taken issue with how the company was “compensating its distributors.”

Still yet, just this month, the FTC filed suit against Neora, alleging that the Texas-based MLM operates as a pyramid scheme, while also deceiving the public about the benefits of its brain health supplements.

Despite mounting criticism and a seemingly endless stream of litigation, this is unlikely to be the end of the MLM. While individual MLM companies have risen and fallen over the years, the model itself – which promises easy money and an alluring community – has withstood a number of court challenges over the years, and will likely continue to do so.

Máire O’Sullivan is a Lecturer in Marketing and Advertising at Edge Hill University. Edits/additions courtesy of TFL.