Counsel for MetaBirkins creator Mason Rothschild is pushing back against Hermès’ trademark suit, filing a motion to dismiss in response to the amended complaint that the Birkin bag-maker filed early this month. While the latest motion and memo of law in support largely mirror the ones that were lodged with the court in February, Rothschild’s counsel does make some noteworthy new points in the wake of Hermès beefing up its complaint, including by diving into the function of non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”), pointing to instances of alleged consumer confusion about the source/nature of the MetaBirkins NFTs on social media and in media reports, and doubling-down on its claim that Rothschild is using MetaBirkins as a trademark and is looking to “expand his MetaBirkins commercial venture.”

At the heart of Rothschild’s new motion is again the argument that Hermès’ trademark infringement and dilution claims should be dismissed based on precedent set out in Rogers v. Grimaldi, which essentially establishes that the use of a trademark in an artistic work is actionable only if the use of the mark has no artistic relevance to the underlying work, or explicitly misleads as to the source or content of the work. Rothschild’s counsel argues that his “fanciful depictions of fur-covered Birkin bags and his identification of his artworks as ‘MetaBirkins’” meet the “low threshold of minimal artistic relevance,” and that there is “nothing explicitly misleading about Rothschild’s depictions of Birkin bags, his use of the ‘MetaBirkins’ name as the title of his art project” and/or his use of the term on his website and social media accounts.

In the newly-filed motion and memo, counsel for Rothschild states that Hermès is attempting “to avoid Rogers by alleging that Rothschild’s identification of his art project by the MetaBirkins name and his use of that name for social media and online accounts dedicated to the art project constitutes ‘trademark use’” of its famous “Birkin” trademark. Taking issue with that approach, Rothschild’s counsel asserts that there is no “trademark use” exclusion from Rogers, and that “the doctrine applies to claims against the name or content of expressive works,” and that “every single one” of Rothschild’s allegedly infringing uses that Hermès identifies “refers to the MetaBirkins digital artworks.”

“It bears repeating,” Rothschild states, “that Hermès does not and cannot allege any uses [of its marks] unrelated to the artworks,” and in fact, “alleges only that Rothschild markets his art by name and uses the obvious modern authentication and promotional tools to do so.”

Citing the facts surrounding the Rogers case, Rothschild asserts that the film Ginger and Fred was “widely marketed by its title, using the marketing channels available at the time, and Rogers specifically considered both the marketing functions of titles and the steps that the defendant took to promote the film.” In the case at hand, Rothschild’s lawyers contend that the fact that the marketing here “involves authentication using an associated NFT and promotion via social media changes nothing,” and thus, Hermès “cannot avoid Rogers just because Rothschild markets his art any more than it can avoid Rogers by repeating the fact that Rothschild sells the art.”

Counsel for Rothschild also takes issue with Hermès’ allegation that Rothschild made additional use of the MetaBirkins name as a trademark by “inviting MetaBirkins fans to submit MetaBirkin designs on the MetaBirkin Discord channel” and making “a few references to new collaborations on the MetaBirkins Instagram page and the page of a collaborator.” Again, Rothschild claims that this falls within the realm of Rogers, with “the referential Instagram comments and the postings by his collaborator [being] analagous to a statement that a new movie was ‘brought to you by the producers of Ginger and Fred.’”

And still yet, Rothschild’s counsel asserted in the motion that the fact that Rothschild “objected to [the creation and sale of] counterfeit MetaBirkins also does not convert the MetaBirkins project into commercial speech that falls outside of Rogers,” arguing that “Ginger Rogers wouldn’t have had a better claim against the producers of Ginger and Fred if they had objected to infringing copies of the film.”

Turning to the second factor in the Rogers test, whether the allegedly infringing trademark use is explicitly misleading as to the source or content of the work. Rothschild argues again, as he did in the original motion to dismiss, that there is nothing that is “explicitly misleading” in his uses of the term MetaBirkins.

“Whether the defendant’s use of the mark is explicitly misleading is not a function of the amount of possible confusion,” Rothschild argues in the new memo, pointing to Ninth Circuit precedent, which states that “[t]he [Rogers] test requires that the use be explicitly misleading to consumers. To be relevant, evidence must relate to the nature of the behavior of the identifying material’s user, not the impact of the use.”

Against this background, Rothshild claims that “Hermès makes much of the fact that a handful of comments on the MetaBirkins Instagram page appear to reflect confusion about what NFTs are, [b]ut these are merely anecdotes, which are hardly surprising in the context of an innovation like an NFT.” And ultimately, “they are irrelevant anyway,” he argues, as “the cases applying Rogers are clear that explicit misleadingness is not judged by whether there is some confusion, but instead by whether that confusion is engendered by explicitly misleading statements.”

With this in mind, and in light of additional arguments also made in the initial memo, including the claim that even if Rogers did not apply, the outcome in Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., which holds that only tangible, physical goods are actionable under the Lanham Act, would bar Hermès’ infringement claims, counsel for Rothschild requests that the court the grant his motion to dismiss Hermès’ complaint in its entirety with prejudice.

Hermès first filed suit against Rothschild in a New York federal court in January, setting out claims of federal and common law trademark infringement, false designation of origin, trademark dilution, cybersquatting, and injury to business reputation and dilution under New York General Business Law. The company is seeking monetary damages, including Rothschild’s profits, and injunctive relief to bar him from making further use of its trademarks, such as by “using any reproduction, copy, counterfeit, or colorable imitation of Hermès’ federally registered trademarks to identify any goods or the rendering of any services not authorized by Hermès.”

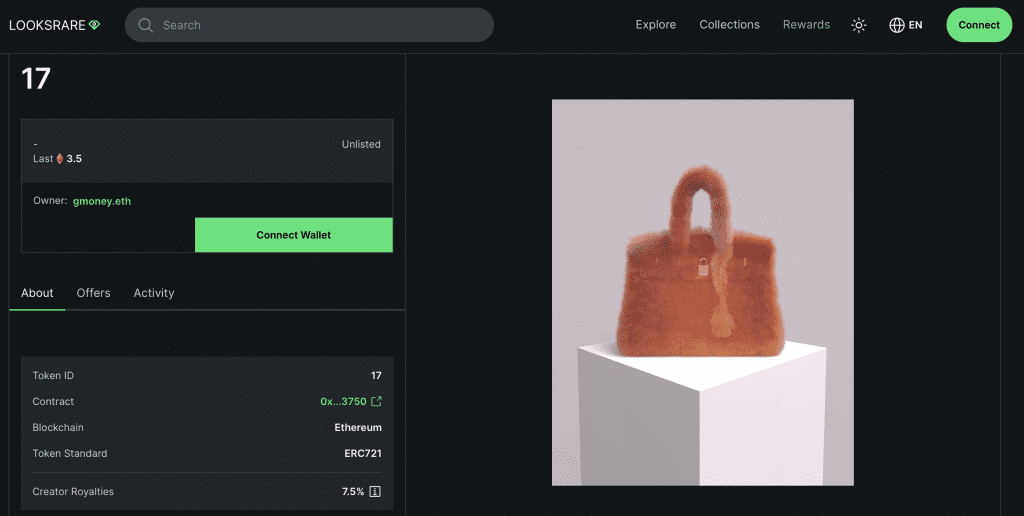

In response to takedowns from Hermès, the NFTs, which are tied to images of furry Birkin-looking bags, were removed from OpenSea and other NFT marketplaces earlier this year. They remain on the LooksRare platform, with one of the NFTs in the collection garnering 3.5 ETH ($2,953.88) in what appears to be the most recent sale, which took place earlier this month.

The case is Hermès International, et al. v. Mason Rothschild, 1:22-cv-00384 (SDNY).