Mason Rothschild has lodged his response to the lawsuit filed against him by Hermès, arguing that the French luxury goods brand’s claims centering on his sale of non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) called “MetaBirkins” should be tossed out in their entirety. In a motion to dismiss and corresponding memo filed on Wednesday, counsel for Rothschild doubled down on the First Amendment arguments that he previously cited in open letters to Hermès, claiming that the rendering of Hermès’ most famous offerings in virtual faux fur “comments on the animal cruelty inherent in Hermès’ manufacture of its ultra-expensive leather handbags,” and thus, enjoys protections from the brand’s headline-making trademark claims.

In the motion to dismiss and memo, as first reported by TFL, counsel for Rothschild (Rebecca Tushnet, Rhett Millsaps, and Chris Sprigman of LEX LUMINA PLLC) sets the stage by stating that Rothschild is “an artist who has created a series of digital artworks that depict and comment on Hermès’ ‘Birkin’ handbags.” The images at issue – and “the NFTs that authenticate them” – are “not handbags,” per Rothschild. “They carry nothing but meaning.” Nonetheless, “Hermès asks this Court to suppress Rothschild’s art and to restrain his protected speech in the service of protecting Hermès’ commercial interest in its trademarks.”

At the core of the motion in response to the MetaBirkins lawsuit are Rothschild’s arguments that Hermès’ trademark infringement and dilution claims should be dismissed based on precedent set out in two key cases: Rogers v. Grimaldi, which essentially establishes that the use of a trademark in an artistic work is actionable only if the use of the mark has no artistic relevance to the underlying work, or explicitly misleads as to the source or content of the work, and Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.

Rogers v. Grimaldi, Dastar

Turning first to Rogers, Rothschild’s counsel asserts that he “has every right to make and sell art that depicts branded products.” That same case law also gives him “the right to identify his depictions of Birkin bags as ‘MetaBirkins’ – a name that both refers to the context in which he makes the art available (i.e., the online, virtual environment popularly dubbed the ‘Metaverse’) and alludes to his artwork’s ‘meta’ commentary on the Birkin bag and the fashion industry more generally.”

Rothschild’s “fanciful depictions of fur-covered Birkin bags and his identification of his artworks as ‘MetaBirkins’” meet the “low threshold of minimal artistic relevance,” his counsel claims, as they “show luxury with no function but communication, luxury emptied of anything but its own image,” and thus, “call into question what it is that luxury lovers actually pay for.” (While Rothschild’s open letters and the MetaBirkins website make explicit mention of the animal cruelty element, the broader comment on luxury appears to be new.)

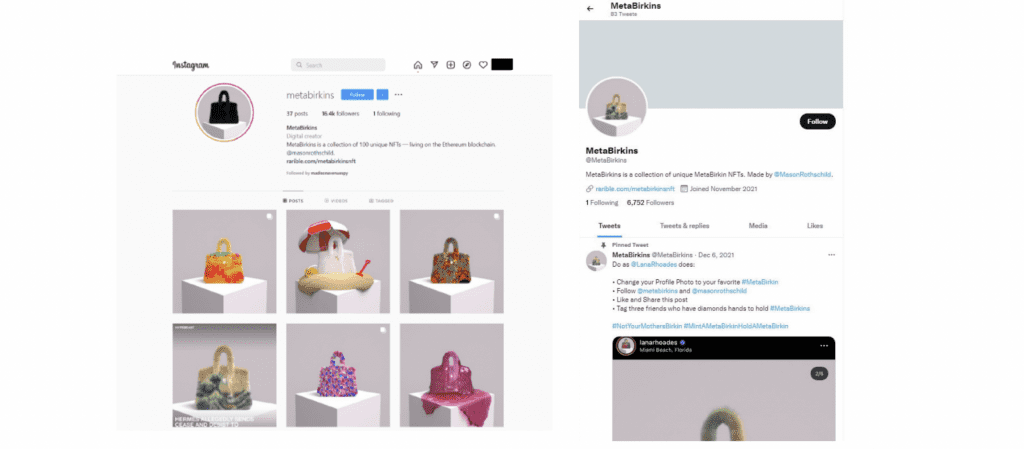

The MetaBirkins similarly meet the second prong of the Rogers test, Rothschild’s counsel claims, as they “do not explicitly mislead about their source or content,” as there is “nothing explicitly misleading about Rothschild’s depictions of Birkin bags, his use of the ‘MetaBirkins’ name as the title of his art project” and/or his use of the term on his website and social media accounts.

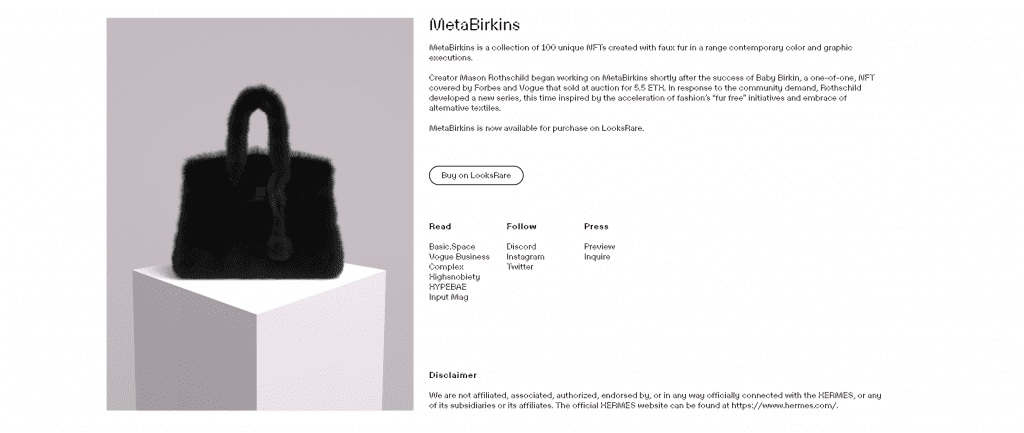

Arguing its point, Rothschild’s counsel asserts that the landing page of the MetaBirkins website “clearly identifies MetaBirkins as Mason Rothschild’s art project, in partnership with Basic.Space (not Hermès), and it describes the MetaBirkins as ‘inspired by the acceleration of fashion’s ‘fur free’ initiatives and embrace of alternative textiles.’” They argue that if consumers draw “any inference … about the relationship between the ‘MetaBirkins’ artworks and Hermès, [it] is not due to anything that is ‘explicitly misleading’ in Rothschild’s uses of the term ‘MetaBirkins.’” (Hermès has, of course, argued otherwise here, claiming that Rothschild is using the MetaBirkins term as an indictor of source.)

As such, they urge the court that Rothschild’s “First Amendment speech rights must take precedence over Hermès’ trademark complaints,” and Hermès’ “straightforwardly defective” claims “must be dismissed under Rogers.”

(Further arguing their point, counsel for Rothschild claims that “Hermès hopes to confuse matters by emphasizing that Rothschild sells his digital artwork by way of NFTs,” but that does not cause “Rothschild’s art does [to] lose its First Amendment protection.” For one thing, they claim that Rothschild offering up the NFTs for sale does not alter their noncommercial nature, arguing that “whenever the commercial aspects of a work are intertwined with artistic content, the First Amendment dictates that the trademark-using speech must be treated as noncommercial.” Moreover, Rothschild’s sale of each digital artwork with an NFT, “the technological means by which Rothschild authenticates his artworks, makes no difference: Rothschild’s First Amendment rights do not depend on how he sells his art any more than they depend on whether he sells it.”)

Even if Rogers were not directly on point and dispositive in this case, “which it is,” Rothschild’s counsel claims, the Supreme Court’s decision in Dastar proves to “be fatal to Hermès’ claims here.” Specifically, Rothschild’s legal team argues that Hermès’ “fundamental complaint” in the lawsuit – namely that consumers will believe that Rothschild’s MetaBirkins “are sponsored by or affiliated with Hermès” – is blocked by the Dastar decision, which “unambiguously holds that only misrepresentations of the origin of physical goods are actionable under the Lanham Act.”

Even without Rogers, “the rule of Dastar is equally clear: confusion as to the origin of intangible creative content is not actionable under the Lanham Act,” per Rothschild.

Hermès’ Dilution Claims

Looking beyond Hermès’ infringement claims to the ones that it makes on the dilution front, Rothschild’s counsel asserts that his First Amendment rights under Rogers similarly “preclude Hermès’ dilution claims, especially given that dilution implicates no countervailing interest in consumer protection.” And wven without Rogers and the First Amendment, they note that “the federal dilution statute expressly excludes ‘noncommercial’ uses,” which is what is at play here, they argue, given the artistic elements of Rothschild’s MetaBirkins. And at the same time, Hermès’ dilution claims do “not cover Rothschild’s use of ‘MetaBirkins’ because his use is referential, rather than being commercial use as a separate mark for an unrelated good or service, as the Lanham Act requires.”

As for Hermès’ remaining claims in the MetaBirkins-centric lawsuit, including false designation of origin and false descriptions and representations, cybersquatting, state dilution and injury to business reputation, etc., counsel for Rothschild claims that they all focus on the “same speech that is protected under Rogers, which rejects the underlying premise of each claim that artistically relevant depictions of trademarks can be wrongful in the absence of explicit falsity,” and thus, should similarly be tossed out.

Consider this a heads up on the latest development in connection with the MetaBirkins lawsuit — more to come on this shortly. As for what brands stand to gain in legal battles over NFTs, we take a look at that here.

The case is Hermès International, et al. v. Mason Rothschild, 1:22-cv-00384 (SDNY).