“It is ironic how much trouble a smile can cause.” That is what Marc Jacobs International (“MJI”) asserts in the beginning of the motion for summary judgment that it filed on Monday. Seeking to get the copyright and trademark infringement case that Nirvana LLC filed against it in December 2018 tossed out of court, MJI asserts that the corporate entity for the famed rock bad falls short in making its case on multiple fronts, including by failing to establish that it maintains copyright or trademark rights in the “ubiquitous” smiley face design at the heart of the case.

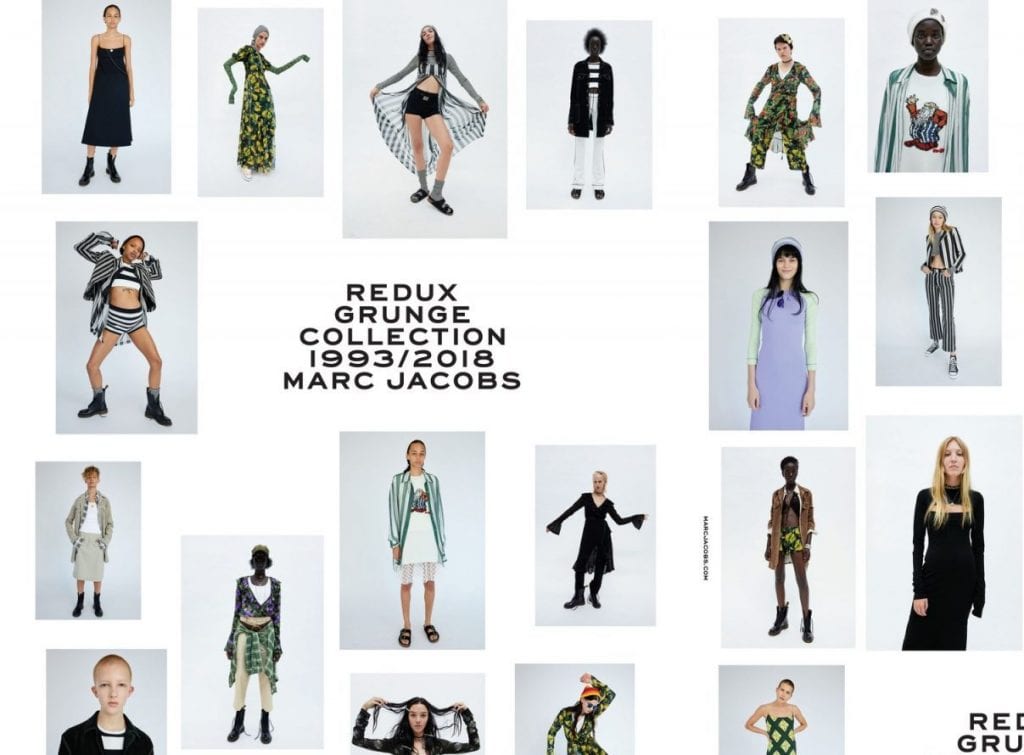

The case got its start on December 28, 2018 when Nirvana LLC – the legal entity formed in September 1997 by Nirvana members Dave Grohl and Krist Novoselic, as well as the Courtney Love-controlled Cobain Estate – filed suit against MJI, as well as MJI stockists Saks Fifth Avenue and Neiman Marcus. At the heart of the suit? “A sweatshirt, tee shirt and socks that contain a graphic of a smiley face with an ‘M’ and ‘J’ for eyes” that were part of the brand’s Grunge Redux collection, a reboot of the controversial grunge wares that designer Marc Jacobs showed in 1993 during his short-lived tenure as creative director of Perry Ellis.

On the heels of the release of the Grunge Redux collection, Nirvana pointed to the squiggly-mouthed smiley face logo that appeared on MJI’s goods, and called out, accusing the brand of copyright infringement, false designation of origin under the Lanham Act, and trademark infringement and unfair competition under California common law.

Following almost two years of back-and-forth between the parties, including an unsuccessful motion to dismiss attempt by MJI, the LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton-owned fashion brand argues in its newly-filed motion for summary judgment that each of Nirvana’s claims should be dismissed as a result of an array of alleged deficiencies on behalf of Nirvana.

Nirvana’s Copyright Claim

First addressing Nirvana’s copyright infringement allegations, MJI claims in its 56-page filing that the copyright claim is barred for a number of reasons, including Nirvana’s “failure to satisfy the preconditions of a valid copyright registration.” Specifically, MJI alleges that many of the statements contained in Nirvana’s copyright registration for the smiley face design – from the name of the author and the publication date to the designation as a “work made for hire” – are “wrong.”

“Had the Copyright Office known about these errors, it would not have issued the registration in the form it is currently in, so the registration as it stands is invalid,” MJI argues. With the allegedly invalid copyright in mind, MJI alleges that “the entire case starts from the false premise that Mr. Kurt Cobain created the tee shirt design” at issue, when – in reality – there is “evidence in the record shows that the creator of the registered tee shirt design is art director Mr. Robert Fisher, who was not an employee of Plaintiff’s processor Nirvana, Inc., the copyright claimant listed on the registration, and who has sworn that he did not transfer his rights anyone.”

(In September, Fisher sought the court’s authorization to join the suit on the basis that he, not the late Nirvana front man Kurt Cobain, was the one who created the x-eyed smiley face design. Fisher claims that he came up with the design in 1991 when he was working on other projects for Nirvana – including the cover of the band’s 1991 album, Nevermind – during his tenure as an Art Director at Geffen Records).

Even if the copyright registration was valid (and MJI says it absolutely is not), the fashion brand contends that Nirvana’s copyright infringement claim should still be dismissed “because there is no substantial similarity” between the protectable expression of Nirvana’s smiley face and the smiley face used by MJI, which is critical, as substantial similarity is the requisite standard for gauging whether two works are similar enough to give rise to a finding of copyright infringement.

Failure to Function

Turning its attention to Nirvana’s Lanham Act claims, MJI argues that the band’s corporate entity fails on this front, as well. Echoing arguments that it made in earlier rounds, MJI asserts that while Nirvana claims that it has trademark rights in the smiley face, the design is not a protectable trademark because consumers cannot possibly link it to Nirvana – or to a single source – because it is “a ubiquitous symbol” that Nirvana “as mere ornamentation and [that] has no inherent or acquired distinctiveness” that would enable the otherwise ordinary symbol to act as an indicator of a single source.

More specifically, MJI states that despite Nirvana’s arguments that the specific smiley face design has “come to symbolize the goodwill associated with Nirvana” since “a significant portion of the consuming public assumes that all goods or services that bear the logo are endorsed by or associated with Nirvana,” Nirvana’s smiley face “is a mere variation of a generic symbol used ornamentally, and is conceptually weak due to widespread use of similar designs on clothing by third parties.”

As such, even if the smiley does function as a trademark, MJI says that Nirvana’s rights in it – and thus, its basis for its infringement claims – are “weak and narrowly circumscribed, and certainly do not encompass all variants of a smiley face design/” Still yet, even assuming any trademark rights exists, MJI claims that there is little likelihood that consumers will confuse its smiley face wares with those of Nirvana, which is the critical inquiry in a trademark infringement matter.

It is significant (from a likelihood of confusion perspective), MJI claims, that its products and Nirvana’s products “are directed to distinct classes of consumers, at different outlets,” as indicated by the fact that the price points of their respective goods “diverge significantly, with the MJI sweatshirt and t-shirt [being] nearly five times the price of the Nirvana sweatshirt and t-shirt, and the MJI socks [being] three times [more expensive than] the price of Nirvana socks.” Not just that, MJI contends that its customers “seek out [its] products for fashion, whereas consumers of Nirvana goods are fans of the band and simply want merchandise reflecting that.” As a result, MJI claims that “consumers will not encounter both MJI and Nirvana products at the same time.”

While such separate chains of distribution and separation of customers may have been true in the past, it is not necessarily indicative of how things work now. Even if, as MJI argues, “the parties sell their goods through different channels and employ different marketing strategies,” the once-very-clear line between different stratums of consumers and segments in the fashion market as a whole is arguably not quite as distinct as it may have been in the past. This comes as a result of the relative interconnectedness of the market, due, in large part, to the widespread embrace of e-commerce/digital marketplaces by brands and consumers. It is also a product of the the marked frequency with which brands – MJI included – collaborate with other, often differently-situated brands, and maintain different collections and price points.

(After all, as of the time of publication, Saks Fifth Avenue was offering up a collection of $125 “The Marc Jacobs Peanuts® x Marc Jacobs” t-shirts. It is worth noting that “The Marc Jacobs” – which is distinct from the main “Marc Jacobs” collection – is the brand’s lower-priced line).

The likelihood of consumer confusion is diminished further by the fact that MJI uses “intricate and thoughtful brand stories regarding [its] collection […] in order to market the products,” the brand contends. (MJI’s argument here is an interesting one given that Nirvana has previously alleged that MJI’s use of the copycat smiley face is just one part of “a wider campaign” by the brand to promote its Grunge Redux collection. Nirvana has claimed that MJI also made unauthorized use of lyrics from Nirvana songs, such as “Come as you are,” in ads for the collection, and display “memes,” such as one “from a video of Nirvana and its co-founder and singer Kurt Cobain performing ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’” on its official Tumbler page – which it co-opted to promote the Grunge collection).

Speaking further to confusion, MJI notes that Nirvana “has failed to present a consumer survey of likelihood of confusion despite having nearly two years and significant financial resources to do so.”

While Nirvana did not present survey evidence, MJI says that it did a survey to “measure the degree to which, if at all, consumers associate the [Nirvana’s] smiley with [Nirvana] or another single, anonymous source.” In connection with that survey, MJI claims that it found that out of 447 consumers (more than 72 percent of which were between the ages of 18-55), “only 10.8 percent of respondents viewed [Nirvana’s] smiley as associated with a single source, and only a mere 9 percent with [Nirvana]” specifically. (Citing McCarthy’s Trademarks and Unfair Competition treatise, MJI states that “it is well-settled that such ‘small percentage results at or less than 10 percent’ are ‘clearly’ ‘not sufficient’ to prove secondary meaning.”)

Such survey evidence “is consistent with the other evidence in the record demonstrating widespread use of iterations of a smiley face design by numerous third parties,” per MJI, and is in line with its argument that “the consuming public is accustomed to encountering smiley face designs on clothing, and simply does not regard the [Nirvana] smiley as an indicia of origin for goods originating exclusively with [Nirvana].”

The survey similarly cuts against a finding of secondary meaning, according to MJI, which further asserts that Nirvana “does not run advertising featuring the smiley standing alone without the term NIRVANA, and there is no evidence of the type of ‘look for’ advertising directed at educating consumers as to the affiliation of the smiley with [Nirvana’s] business.”

With the foregoing in mind, MJI claims that Nirvana has failed to prove that it has a valid, protectable trademark, and that there is a likelihood of consumer confusion between that mark and MJI’s smiley face. As such, MJI asserts that Nirvana’s remaining claims under California common law are premised on the same conduct underlying the infringement claims under federal law, and should similarly fail, and that the court should grant its motion for summary judgment and dismiss all of Nirvana’s claims in the case, which it claims “has been advanced in bad faith since the beginning.”

*The case is Nirvana LLC v. Marc Jacobs International, LLC, et al., 2:18-cv-10743 (C.D.Cal).