The most exciting aspect of the fashion industry at the moment is not on the runway, or on brands’ increasingly high-activity, often collaboration-spotlighting Instagram accounts. It is certainly not at the original point-of-sale for most luxury branded wares, nor can it be found in the high-powered creative director and branding switch-a-roos often underway in the upper echelon of the industry. The hottest developments in fashion are a step removed: they are at resale. That is where a growing string of acquisitions and significant fund raising, is underway, at least.

On the heels of FarFetch revealing that it would acquire Stadium Goods, the buzzy New York-based sneaker consignment site that attracted the attention (and funds) of luxury goods conglomerate LVMH roughly a year prior, and before that, when rival conglomerate Richemont snapped up second-hand watch-selling platform Watchfinder, Rebag announced this week that it has landed $25 million in Series C funding.

The latest round, which brings the luxury handbag reseller’s total funding to $52 million, will see the company expand upon its existing brick-and-mortar stores in New York and Los Angeles by way of “an accelerated retail expansion plan;” scale its technology and product team “to further refine its proprietary pricing and luxury handbag evaluation tools;” and bolster its leadership team.

The York-based reseller – which was founded in 2014 by Charles-Albert Gorra, a Harvard Business School alum and business development veteran from Rent the Runway, and Erwan Delacroix, previously of Google – describes itself “an end-to-end luxury resale service that rethinks the role of luxury in the secondary market.”

One of its key points of differentiation from the other seemingly similar sites out there? Unlike most of its resale market peers, which operate on a consignment or per-to-peer marketplace basis, Rebag has shunned the get-paid-only-if-your-product-sells model. Instead, if Rebag’s team accepts a bag based on a seller’s submitted photos, they pay the seller a “fair market price” upfront, and list it on their e-commerce site, one that currently boasts everything from hard-to-find Chanel bags to an array of Hermès Birkins and Kellys.

Rebag joins a larger pool of budding young companies aiming to give luxury and other in-demand goods (i.e., sneakers and streetwear) a second lease on life in the resale realm. Beyond the previously mentioned Stadium Goods and Watchfinder deals is investment activity involving Detroit-based Stock X. Described as “the NASDAQ of sneakers,” the barely-3-year-old company announced in September that it had raised $44 million from investors, including model/entrepreneur Karlie Kloss, DJ Steve Aoki, streetwear designer Don Crawley (aka Don C), and Salesforce chairman Marc Benioff, bringing its total funding to $50 million.

Luxury consignment site, The RealReal, has consistently made headlines for its funding – a total of $288 million since its founding in 2011. As recently as last month, the San Francisco-based company was revealed to be eyeing a potential initial public offering in the near future.

Still yet, Grailed, the curated menswear resale site, took on a $15 million investment in June in a Series A round led by Index Ventures, bringing the company’s total funding to about $20 million. And following from that menswear/streetwear/sneaker-centric investment, Foot Locker publicized just this week that it is making a “strategic minority investment” of $100 million in GOAT Group, the operators of the popular secondary sneaker market, GOAT.

The traditional footwear retailer stated on Thursday, “Over time, Foot Locker and GOAT Group will combine efforts across digital and physical retail platforms to create exclusive customer experiences.” While, Eddy Lu, the co-founder and Chief Executive Officer of GOAT Group, boasted about the group’s pioneering of the “ship-to-verify model with a mission to bring a seamless and safe customer experience to the secondary sneaker market.”

Something Old, Something New

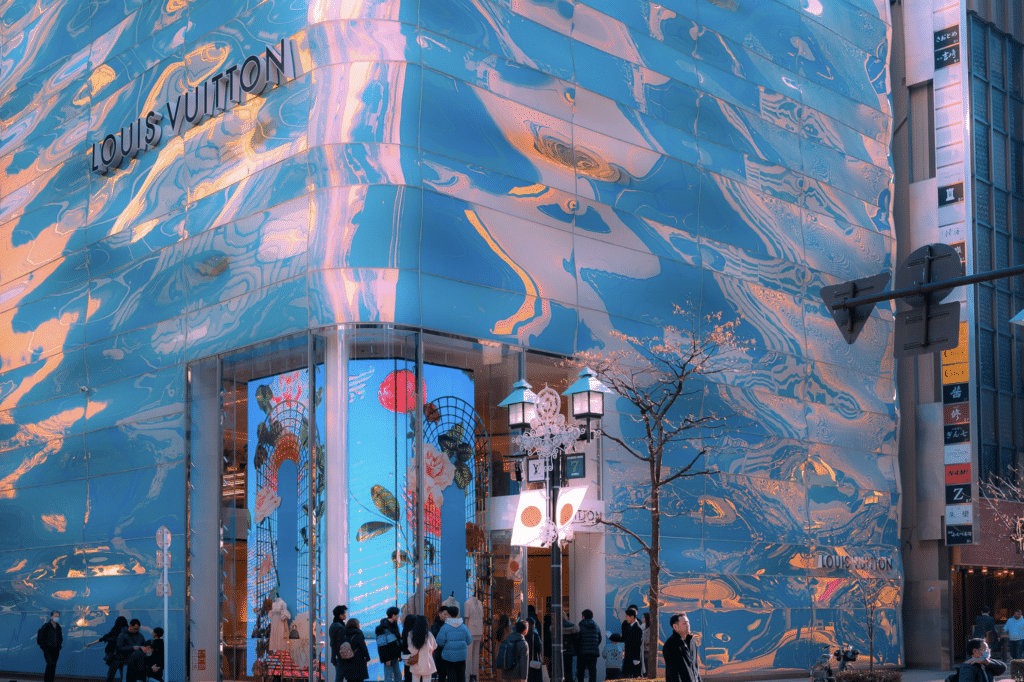

So, what is driving this push of venture capital and brand acquisition interest? It is an array of factors, of course, not least of which is the ease and accessibility of luxury resale sites. In fact, many of these resale sites are actually standing in place of the slow-to-adapt luxury brands, themselves, which refuse to offer up many of their handbags for sale online. In other words, a consumer can find an array of Chanel bags – albeit good condition, pre-owned ones – on Rebag. They cannot, however, purchase a new Chanel bag – or some of the most coveted Hermès, Celine, Dior, and Louis Vuitton bags – with a click of the mouse or a click of an iPhone app; they must visit one of the brand’s brick-and-mortar stores to do so.

This holds true for the likes of purposely-limited edition streetwear products and sneakers, which are often unattainable at retail. Adidas’ wildly buzzy Yeezy collection with rapper Kanye West was an apt demonstration of this, as quantities were kept so small for the vast majority of the parties’ partnership that consumers were often forced to look to sites like Stock X if they wanted to get their hands on the shoes at all.

Beyond the pure ease of e-commerce, resale sites by virtue of their lower-than-initial-retail prices attract a whole slew of consumers that would otherwise not be luxury shoppers, leading many resale owners and analysts, alike, to liken these businesses to a “point of entry” for young consumers not yet flush enough with cash to buy a quilted Chanel flap bag at retail.

That same demographic is enticed by the “treasure-hunt experience” that secondhand shopping provides, without the hassle of leaving their couches.

These factors, among others, are why mass-market fashion resale site, Thredup, projects that the total resale retail market will reach $41 billion in revenue by 2022. That figure is less than the $53.4 billion in total revenue at luxury goods conglomerate LVMH brought in for 2018, but it is not to be discounted, as “in a world where sales are swiftly declining for the many big retailers, that’s huge growth in market share,” per analyst Richard Kestenbaum.

Beyond this segment’s growing marketshare, the pure interest (and money) coming in from all angles, whether it be consumers or the big luxury conglomerates, themselves, as well as the very high-stakes fights that at least one brand is waging in an attempt to exert control over this burgeoning aspect of the luxury economy, are sure-fire indications that this part of the market is the one worth keeping a close eye on.