LuLaRoe has agreed to settle one of the many striking cases that have waged against it in recent years. On Tuesday, Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson revealed that the Corona, California-based multi-level marketing company (“MLM”) will pay almost $5 million to settle the lawsuit that the state of Washington filed against it and several of its executives in early 2019, accusing the headline-making apparel company of operating as a pyramid scheme in violation of the Anti-Pyramid Promotional Scheme Act, as well as Washington’s Consumer Protection Act, all while promising to help women achieve financial freedom.

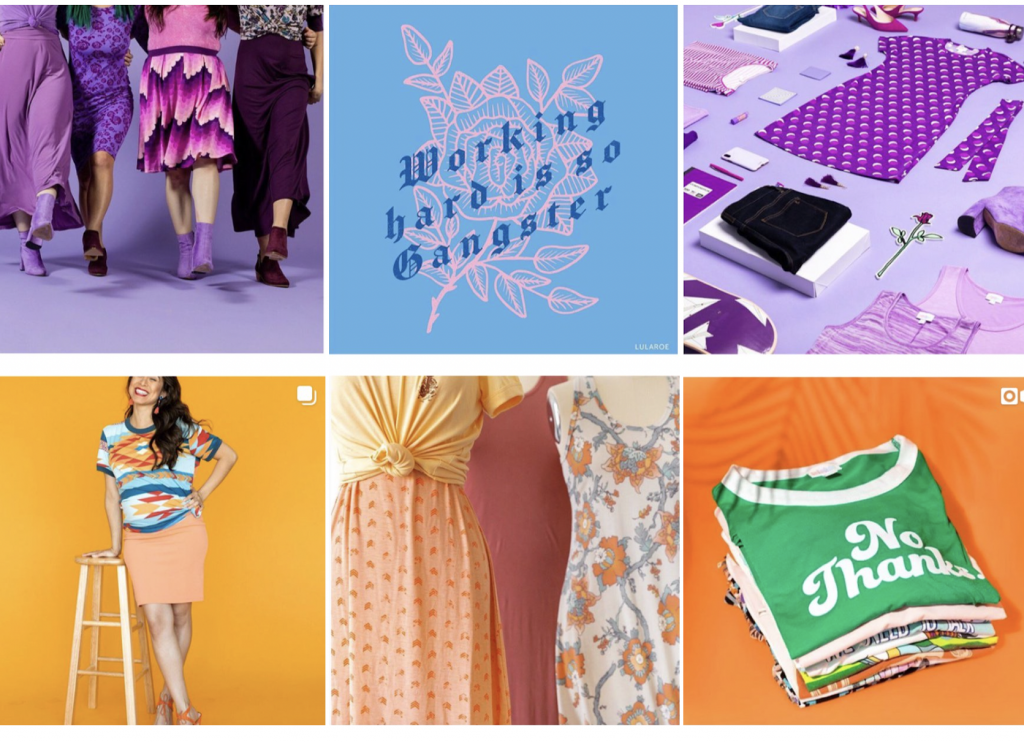

Formally launched in 2013 by DeAnne Stidham, who was a single mother of seven children when she launched the company, according to the company’s (since-edited) website, LuLaRoe rose to fame thanks in large part to its network of tens of thousands of commission-based “consultants” scattered throughout the U.S. Fueled mostly by stay-at-home moms in search of extra cash and by Facebook posts that boasted about LuLaRoe’s colorful, comfortable clothing, including its much-buzzed-about printed (and defective) leggings, LuLaRoe was reportedly generating $2.3 billion annual revenue in 2018, “making the five-year-old brand about the size of J.Crew,” according to Bloomberg, and earning it the title of one of the largest MLM companies in the U.S.

As the thriving business that Stidham was running with her husband Mark Stidham was in the midst of sky-rocketing growth (it booked sales gains of 600 percent as of 2016, per CBS), it swiftly started to implode. The chips started to publicly fall in 2017 when LuLaRoe was named in a flurry of widely-publicized class action lawsuits, including one that sought $1 billion in damages, and another that accused the company of violating the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, the federal statute enacted in 1970 to provide the government with tools in the fight against organized crime. Regardless of the points of differentiation between the various lawsuits filed in courts across the U.S., all of them painted the company as little more than a toxic “pyramid scheme,” and accused it and its founders of scamming women across the country out of millions of dollars.

Among those suits: the case filed by Washington State, which asserted in its January 25, 2019 complaint that the company’s former bonus structure constituted a pyramid scheme, while “its claims regarding sustainability, profitability, and inventory refunds” amounted to legally-actionable examples of deceptive marketing.

At the heart of the Washington State case is the allegation that LuLaRoe is not actually an MLM business but an illegal pyramid scheme. While pyramid schemes “can look remarkably like legitimate MLM business opportunities,” according to the Federal Trade Commission, the difference between the two is that in pyramid schemes an individual’s “income is based mostly on how many people he/she recruits, not how much product he/she sells.” That is precisely how LuLaRoe was operating before the company changed its bonus structure in July 2017, according to Washington State, which asserted that LuLaRoe “incentivized existing consultants to recruit and sponsor new consultants, and to encourage them and their recruits to purchase large amounts of inventory, by basing its bonus structure on the dollar amount of wholesale orders paid for, instead of on bona-fide retail sales to end-consumers.”

The result, according to the state’s suit, was an illegal pyramid scheme – with the name referring to the fact that most participants fall in the lowest income tier and far fewer occupy the top spots – that violates Washington’s Anti-Pyramid Promotional Scheme law. (The company changed this bonus structure in July 2017 to provide bonuses based solely on sales to consumers.)

In case that was not enough, the complaint accused LuLaRoe of making “deceptive claims” about the nature of its business model and profitability in order to encourage more consumers to become consultants. For example, Washington State alleged that “the company’s annual disclosure statements only include ‘active’ consultants who have met minimum purchase thresholds,” thereby, “omitting consultants who fared worse.” At the same time, “LuLaRoe never published a 2017 Income Statement, leaving a 2016 Income Statement on its website, which was not reflective of 2017 when business declined.” As a result, the company “misled prospective consultants who evaluated whether to join” the company in 2017.

Beyond that, “LuLaRoe tricked consumers into buying into its pyramid scheme with deceptive claims of high profits and refunds for unsold merchandise.” For instance, the company “advertised that consultants could make ‘full-time pay’ for ‘part-time work,’” and highlighted consultants who made $10,000 to $500,000 a month, promising that LuLaRoe “is a business that is going to bring in a lot of money for you, a lot of money.” Counsel for Washington State argued that “the pyramid scheme structure ensured that the primary business opportunity from joining LuLaRoe was through recruiting, not retail sales,” and as a result, “a majority of Washington consultants reported less than $10,000 profits in total from their LuLaRoe business, and nearly one-third of consultants reported losses.”

And all the while, the company allegedly violated the state’s Consumer Protection Act by “misrepresenting and failing to honor its refund policies.” LuLaRoe warranted that unsold merchandise “would be refunded at 100 percent, plus free shipping, should the consultants decide to stop selling for LuLaRoe.” The state asserted that such a claim turned out not to be true, and therefore, “Many Washingtonians lost money and were left with piles of unsold merchandise and broken promises from LuLaRoe.” After all, in order to become a LuLaRoe “consultant,” new members are required to purchase “onboarding packages” that consist of LuLaRoe garments and that range in cost between $5,000 and upwards of $9,000.

“A survey of 215 current and former consultants, conducted by Flynn, the consultant in Florida, puts the typical initial investment at about $7,000,” Bloomberg reported in 2018, noting that “this is unusually high for a direct selling company; Mary Kay, for example, offers a $100 makeup starter kit.”

According to a CBS investigation in 2017, LuLaRoe also recommended that “salespeople keep about $20,000 in inventory at any given time and encourages consultants continually to invest in their businesses,” all under the guise that unsold merchandise could be returned to the company in exchange for a 100 percent refund. “Despite the company’s buyback policy – in connection with which LuLaRoe has vowed to buyback 100 percent of a consultant’s unsold inventory that is in ‘acceptable condition’ if a consultant wishes to cease working with the company – it has ceased to do so,” CBS found.

Fast forward to this week, and the Attorney General’s Office has revealed that LuLaRoe has agreed to pay $4.75 million to settle the state’s case, albeit without admitting any wrongdoing.

As first reported by the AP, Attorney General Bob Ferguson confirmed that “$4 million of the settlement will be distributed to about 3,000 Washington residents who were recruited to the company.” In a statement, Ferguson said on Tuesday, “Every Washington retailer who lost money under LuLaRoe’s pyramid structure will receive restitution.”

*The case is State of Washington v. LuLaRoe, 19-2-02325-2 SEA.