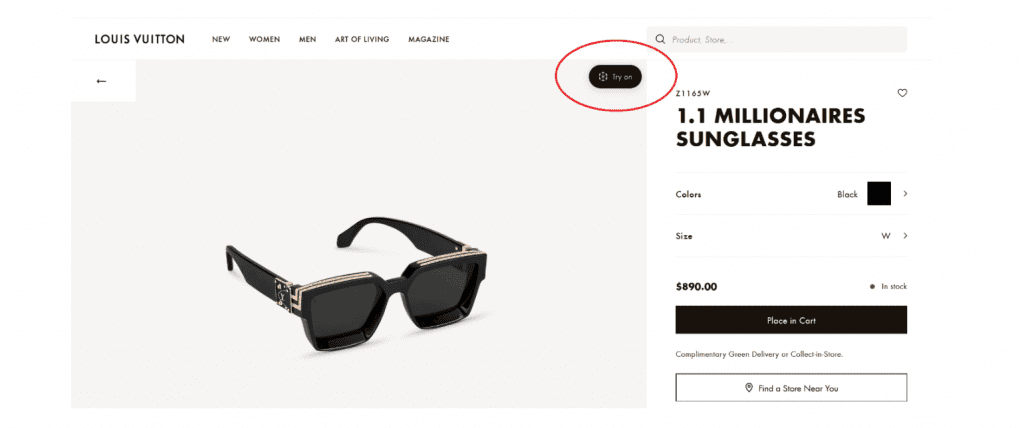

Louis Vuitton North America is coming under fire in a new lawsuit for allegedly collecting consumers’ biometric data in connection with a virtual try-on tool on its website. According the complaint that she filed on April 8, plaintiff Paula Theriot claims that Louis Vuitton North America (“Louis Vuitton”) “sells the image of luxury to consumers, inviting them to virtually ‘try on’ its designer eyewear through its website’s ‘Virtual Try-On’ feature.” The problem with that, Theriot argues, is that by enabling Louis Vuitton to access images of their faces, consumers are providing the brand with “detailed and sensitive biometric identifiers and information, including complete facial scans,” which the brand allegedly collects and stores “without first obtaining their consent, or informing them that this data is being collected.”

In the newly-filed lawsuit, Theriot alleges that “unbeknownst to its website users, including [herself],” Louis Vuitton “collects detailed and sensitive biometric identifiers and information, including complete facial scans, of its users through the Virtual Try-On tool.” Despite consumer concerns regarding facial-scanning technology, Theriot asserts that Louis Vuitton “refused, and continues to refuse, to inform users that it is using technology on its website to collect their biometric facial scans, and neither informs users that their biometric identifiers are being collected, nor asks for their consent.”

Beyond consumers’ privacy concerns and their expectations that “companies will follow the law in promoting and advertising [their] products,” Theriot claims that Louis Vuitton’s alleged practice of collecting consumers’ biometric data runs afoul of the “clear mandate” created by Illinois’s Biometric Information Privacy Act (“BIPA”).

Enacted in 2008, BIPA requires “private entities, including companies like Louis Vuitton, that collect certain biometric identifiers or biometric information, or cause such information and identifiers to be collected, to take a number of specific steps to safeguard the biometric data they collect, store, or capture.” (Under BIPA, a “biometric identifier” generally means “a retina or iris scan, fingerprint, voiceprint, or scan of hand or face geometry” and “biometric information,” means “any information, regardless of how it is captured, converted, stored, or shared, based on an individual’s biometric identifier used to identify an individual.”) Such steps include – but are not limited to – “obtain[ing] informed consent from consumers prior to collecting such data from them,” Theriot argues, and “publicly disclos[ing] to consumers their uses, retention of, and a schedule for destruction of the biometric information or identifiers that they do collect.”

Theriot contends that she “never provided a written release to [Louis Vuitton] authorizing it to collect, store, or use her facial scans or facial geometry, and was never informed, in writing or otherwise, about the purpose for collecting her biometric data,” and upon reviewing the luxury brand’s website terms and conditions, “did not see any indication that her biometric information would be collected or distributed in those website terms and conditions.”

Hardly a one-off occurrence, Theriot claims that Louis Vuitton has violated BIPA and continues to violate it “each and every time a website visitor based in Illinois uses the Virtual Try-On tool because Louis Vuitton continues to collect and store or facilitate the storage of biometric information or biometric identifiers without disclosure to or consent of any of the consumers who try on glasses on their website, necessarily using [its] Virtual Try-On tool to do so.”

With the foregoing in mind, Theriot alleges that Louis Vuitton has violated BIPA, namely, by way of its “failure to inform in writing and obtain written release from users prior to capturing, collecting, or storing biometric identifiers” and “failure to develop and make publicly available a written policy for retention and destruction of biometric identifiers.” As such, she is seeking authorization from the court that the case can proceed as a class action, thereby, enabling other individuals to join, as well as monetary damages and injunctive relief to force Louis Vuitton to comply with BIPA.

Louis Vuitton is not the only company on the receiving end of a currently-pending BIPA lawsuit. A similar case was filed against Target in a federal court in Illinois in October 2021, with the plaintiff accusing the retailer of making use of a virtual try-on feature that unlawfully captures, collects, and stores consumers’ biometric data through facial geometry scans. In that case, plaintiff Aimee Potter claims that Target enables consumers to test makeup products virtually by either scanning or uploading a photo of their face to its app, but fails to obtain consent to collect consumers’ biometric data and also fails to inform consumers that it is collecting such data.

Both cases – and others like them – reflect the risks that are at play as “more and more retailers introduce virtual try-on tools that use biometric technology to recreate the fitting room experience for their online consumers,” particularly in the wake of the pandemic, per Steptoe & Johnson attorneys Stephanie Sheridan, Meegan Brooks and Surya Kundu.

Against this background and given that virtual try-on features are serving as more than merely a pandemic trend and instead, a notable step in furtherance of a larger omnichannel retail revolution, and given the potential for more states to pass BIPA-like laws of their own, it is important for private entities that collect – or may start collecting – biometric data from consumers to consider best practices for maintaining public-facing privacy policies, appropriate consents and notices, and data security safeguards, among other things.

A rep for Louis Vuitton was not immediately available for comment.

The case is Theriot v. Louis Vuitton North America, Inc., 1:22-cv-02944 (SDNY).