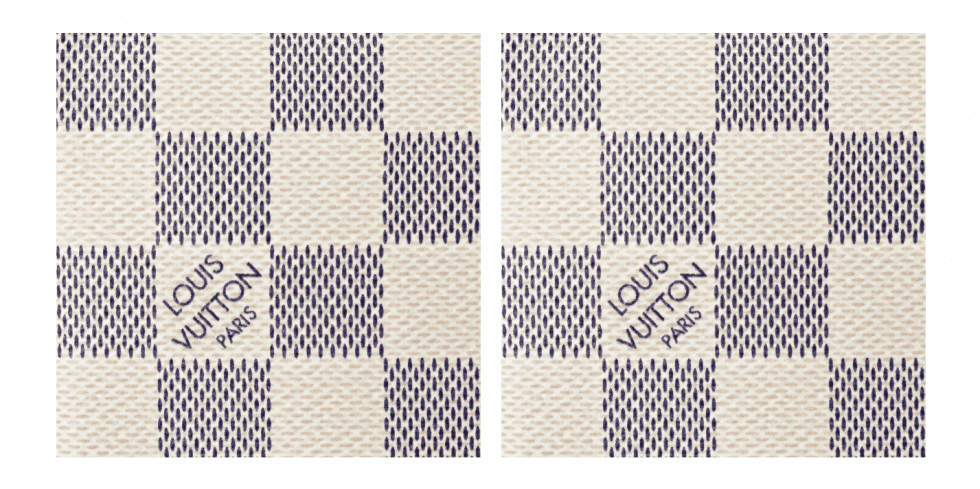

A long-running trademark back-and-forth over one of Louis Vuitton’s checkerboard patterns has resulted in a loss for the French luxury goods titan. In a decision on Wednesday, the European Union’s General Court determined that the Board of Appeal of the European Union Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”) got it right when it found that Louis Vuitton had not demonstrated that its white and blue Damier Azur pattern had acquired distinctiveness – for use on leather goods (in Class 18) – through its use of the checkered mark in the 27 European Union member states, and as a result, Louis Vuitton is not entitled to trademark registration for the pattern for use on things like handbags, backpacks, change purses, and luggage.

Setting the stage in its newly-issued decision, which stems from an invalidity bid that was first waged with the EUIPO’s Cancellation Division back in 2015 over Louis Vuitton’s EUIPO-registered Damier Azur trademark, the General Court states that “as a preliminary point,” the same court previously held in a decision in June 2020 that the Board of Appeal correctly found that the Louis Vuitton Damier Azur trademark lacks “inherent distinctive character,” and thus, the brand would need to show that the mark has acquired distinctiveness in order to benefit from trademark registration. With that in mind, the court here asserts that “this action relates solely to whether the contested Louis Vuitton trademark has acquired a distinctive character” as a result of use by Louis Vuitton.

(Following the June 2020 decision of the General Court, the case was sent to the EUIPO’s Fifth Board of Appeal, which, after examining the evidence submitted by Louis Vuitton, held that the Paris-based brand had not demonstrated that the Damier Azur mark had acquired distinctiveness (through the use of the mark) and dismissed the matter. Louis Vuitton appealed and the case ended up before the General Court again.)

As another initial point, the General Court states that in accordance with Article 7(1)(b) of the EUTMR, trademarks that are “devoid of any inherent distinctive character” are not to be registered. However, it also claims that the registration of such a mark may avoid being declared invalid if, as a result of use of the mark after registration, “it has acquired distinctiveness in relation to the goods or services for which it is registered.”

Acquired distinctiveness – or a showing that consumers directly associate a mark with a single of goods/services due the holder’s extensive use and promotion of the mark – “requires that at least a significant proportion of the relevant public identifies the goods or services concerned as originating from a particular undertaking, because of that mark,” the court contends, noting that a trademark holder must demonstrate “either that [the mark] had acquired distinctive character through use … prior to the date on which the application for registration was filed, or that the mark had acquired such character through use that had been made between the date of its registration and the date of application for a declaration of invalidity.”

This calls for “an overall assessment” of the evidence provided by the trademark holder (Louis Vuitton here), with the court pointing to a handful of factors as critical for making such a determination. These factors, which closely mirror the factors for gauging secondary meaning in the U.S., include: (1) The market share held by the mark; (2) how intensive, geographically widespread and long-standing the use of the mark has been; (3) the amount invested by the trademark holder in promoting the mark; (4) the proportion of the relevant public who, because of the mark, identify products as originating from a single source; (5) statements from chambers of commerce and industry or other trade and professional associations; and (6) consumer survey evidence.

The General Court’s Decision

Against that background, the General Court turns to the findings of the Board of Appeal, which Louis Vuitton argued were based “on a limited amount of evidence, specifically regarding the Member States concerned” (namely, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Slovenia), and thus, the Board “failed to make an overall assessment of all the evidence [it was] presented” with by the brand. According to the General Court, the Board of Appeal did not get it wrong when it decided to “examine first whether the contested mark had acquired distinctive character through the use that had been made of it in Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Slovenia,” and then “proceed to such an examination in respect of the other EU Member States only if distinctive character acquired through use had been demonstrated for the Member States concerned.”

The significance of Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Slovenia, in particular, is that those are Member States, together with Malta, where Louis Vuitton does not have any stores. (In order to show that “the relevant public” in those States have been exposed to the Damier Azur mark, Louis Vuitton submitted evidence, including “a selection of invoices corresponding to sales of goods in Class 18 bearing the contested mark to persons residing in [those States],” which the Board generally found to be insufficient to establish that relevant public “recognizes the commercial origin of the goods concerned when confronted with that mark.”)

Siding with the EUIPO, the Court determined that the Board did, in fact, “carry out an overall assessment of all the relevant evidence, as required” by law. “Interestingly, the Court also rejected Louis Vuitton’s argument that the analysis carried out by the Board [was] ‘detached from reality, since it ignores the fact that, throughout the European Union, consumers engage in homogeneous behavior with regards luxury brands, particularly because they travel and use the internet regularly,’” Eleonora Rosati, the Director of the Institute for Intellectual Property and Market Lab at Stockholm University, wrote here. “That argument is too general in nature,” according to the General Court, which asserted that “given that the burden of proof of the acquisition of distinctive character through use lies with the proprietor of the mark, it is for the proprietor to adduce specific and substantiated evidence for that purpose.”

Ultimately, the General Court found that the Board of Appeal “did not err in finding that the applicant had not demonstrated that the contested mark had acquired distinctive character through its use in Lithuania, Latvia, Slovakia, Slovenia or Bulgaria,” and thus, since Louis Vuitton “has not … demonstrated that the contested mark had acquired distinctive character through its use in all the Member States of the European Union, the action must be dismissed in its entirety.”

Reflecting on the General Court’s decision, Rosati claims that “on an anecdotal level,” the outcome “is quite telling of the difficulty of registering or as in this case, maintaining the registration of a less conventional mark if even an undertaking like Louis Vuitton” – which maintains the title of the largest luxury brand in the world by revenue – “has failed.” From a big picture point of view, she says that the decision (and the outcome in the Dior Saddle bag matter, as well) makes it “clear once again that when it comes to marks of this kind, distinctiveness – whether inherent or acquired – is a real issue and the path to a finding of acquired distinctiveness is by no means an easy (or even walkable) one either.”

For some stateside context: Louis Vuitton maintains registrations for its various Damier marks in the U.S., such as this one for use on leather goods. In amassing such registrations, counsel for Louis Vuitton has overcome failure to function refusals, arguing in response on more than one occasion that courts have “specifically found that the Damier designs are recognized as trademarks,” which is helped by the fact that the print is not “merely a ‘repeating checkerboard pattern,'” but a unique composition that includes the “distinctive LOUIS VUITTON name above PARIS printed on one of the squares.”

The brand similarly boasts registrations in the U.S., such as this one, for the Damier pattern sans the inclusion of “LOUIS VUITTON PARIS.”

The case is Louis Vuitton Malletier v. European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), T‑275/21.