The rise of legalized marijuana in 33 states, 10 of which have given the still federally-sanctioned drug a green light for recreational use, has resulted in a nearly $10 billion market that is expected to top $57 billion by 2027. Beyond the influx of new ventures, an explosion of jobs (as highlighted by the New York Times this weekend), a bevy of anticipated American initial public offerings in the cannabis sector, and the increasing marketing of marijuana in the luxury sphere is another area in which marijuana is expected to make a marked impact: legal protections.

In addition to the impending flood of U.S. cannabis companies that will inevitably follow in the footsteps of their Canadian counterparts and look to raise cash by way of the stock market is the likelihood that many of those same companies will also attempt to legally protect novel cannabis-related inventions, including the strains, themselves. The latter of which can be protected by way of a special type of patent, the oft-overlooked sibling of the much more frequently utilized design and utility patents.

Plant patents – which give an inventor 20 years of exclusive rights, including the potentially-very-lucrative ability to license the particular strain to others for commercial use – came about in the U.S. thanks to Plant Patent Act of 1930, federal legislation aimed at incentivizing the U.S. private sector to develop new plant varieties, including “new disease-resistant, drought-resistant, and cold-resistant plants to extend the variety of edible crops and reduce the risk on plants of natural plights, such as extreme weather.”

As of late, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) has seen the filing of a growing number of cannabis-specific patent applications, both of the utility and plant kind. Last year, the USPTO “issued 39 patents containing the words cannabis or marijuana in their summaries, up from 29 in 2017 and 14 in 2016,” per Reuters, a number that – based on the number of patent applications already filed this year – will likely only grow further for both plants and utility patents, the latter of which can likely be relied upon to protect cannabinoid chemical compounds.

In terms of plant patent applications, alone, which are routinely significantly outnumbered by utility and design patent applications, the adjudicator of U.S. patents is currently seeing growth in this arena, with applications being filed for the likes of a “new and distinct Cannabis plant named ‘DD-CT-BR5,’ [which] is distinguished by its trichome density, dried flower yield and max THC content.”

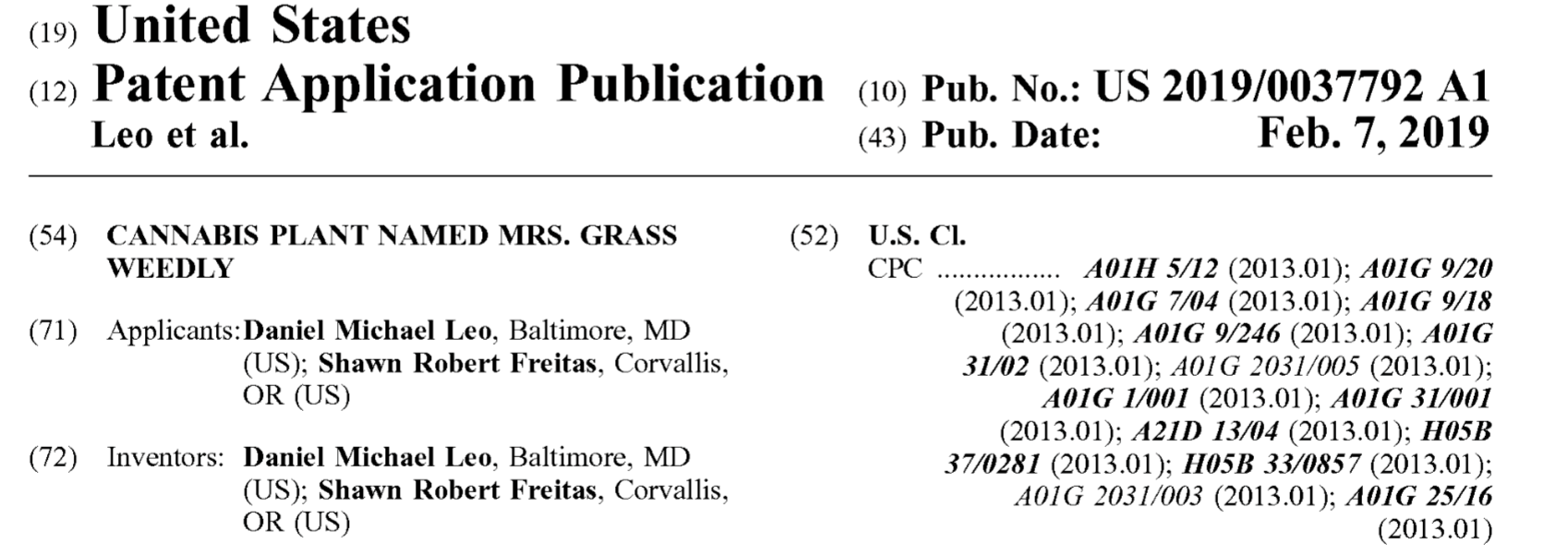

Another recently-filed plant patent application centers on “a new and distinct hybrid plant named `Mr. Grass Weedly` characterized by a hybrid between Cannabis sativa L. ssp. Sativa. times. Cannabis sativa L. ssp. Indica.” Another is for a “Cannabis plant named ‘LW-BB1,’ a high yielding female cannabis cultivar, [which] shows strongly apically dominant vertical branches, vigorous growth and dark green foliage.”

Still yet, “a new and distinct Cannabis sativa L. ssp. indica plant named Erez,” which is, according to the plant patent application, “characterized by a high amount of Cannabidiol of greater than approximately 16 percent and a higher amount of THC of about 23 percent.”

These applications join a small number of marijuana-specific plant patents, such as a “Cannabis plant named ‘Ecuadorian Sativa,’” which, despite the fact that the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency considers marijuana products to be illegal, have been granted patent protection.

Much like utility and design patent-protected creations, in order to be protected by law, a plant must be novel and non-obvious, but more than that, the new variety of plant must be created asexually (and not simply grown from seeds or discovered in the wild).

This particular body of inventions will prove an interesting one to watch as it is uncharted territory, largely because of the traditionally illegal nature of marijuana. While most other patent-filers have scores prior art (i.e., similar, already-existing inventions) to cite in their applications, those seeking to claim exclusive rights in strains of cannabis certainly have less to put forth. “Because of 80 years of prohibition, there is a massive lack of prior art documentation for cannabis,” said Beth Schechter, executive director of the Open Cannabis Project, told Reuters.

The publication’s Jan Wolfe notes, for instance, “Because marijuana has been illegal, many of its uses have not been written about in the sort of scientific articles typically presented as prior art in patent cases.” With this in mind, experts say the marijuana industry is not only in the very early stages of rights-seeking but is “largely ill-prepared for patent litigation and battles over licensing fees that may lie ahead.”