On the heels of being slapped with a $10 million trade dress infringement, fraud, and unfair competition lawsuit in May by burgeoning womenswear brand dbleudazzled, Khloe Kardashian and her brand, Good American, want the court to strike the two unfair competition claims lodged against them by dbleudazzled, alleging that they are based on the company’s unmerited allegation that they made “public statements [about the lookalike bodysuits that they allegedly copied from dbleudazzled] that were false or misleading to consumers,” when the statements are, in fact, true.

According to the motion to strike that counsel for Kardashian and her 4-year old Good American brand (the “defendants”) filed in a California Superior Court on August 4, the court should toss out dbleudazzled’s unfair competition claims because those claims depend on the challenged statements being “false and deceptive to consumers” when the statements are “absolutely true.” More than that, though, the claims should be struck, the defendants assert, because they fall within the bounds of California’s anti-Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (“SLAPP”) statute, and thus, should be dismissed in order to protect the defendants’ “constitutionally protected speech.”

Kardashian, Good American’s Anti-SLAPP Claims

Setting the stage for its anti-SLAPP claims, Kardashian and Good American assert that dbleudazzled’s “unfair competition claims present a classic case of trying to suppress a victim’s public response to a series of widely publicized fabrications, [which is] precisely the kind of protected speech the anti-SLAPP laws were enacted to safeguard.” Enacted in 1992, California’s anti-SLAPP statute protects parties from lawsuits brought to “chill the valid exercise of constitutional rights of free speech,” and provides parties with the ability to file a special motion to strike a complaint or parts of a complaint when a case has been filed “primarily to discourage speech about issues of public significance,” which is precisely what the defendants claim is going on in the case at hand.

Specifically, Kardashian and Good American claim that dbleudazzled “relies on three of [their] statements … as the basis for [its] unfair competition claims,” arguing that the claims are false and misleading, and therefore,“constitute a fraudulent business practice” in violation of the California state law, which characterizes “any unlawful, unfair, or fraudulent business act or practice, or false, deceptive, or misleading advertising” as unfair competition, and assumes that the plaintiff can prove “suffering and financial or property losses” due to the allegedly unfair practice.

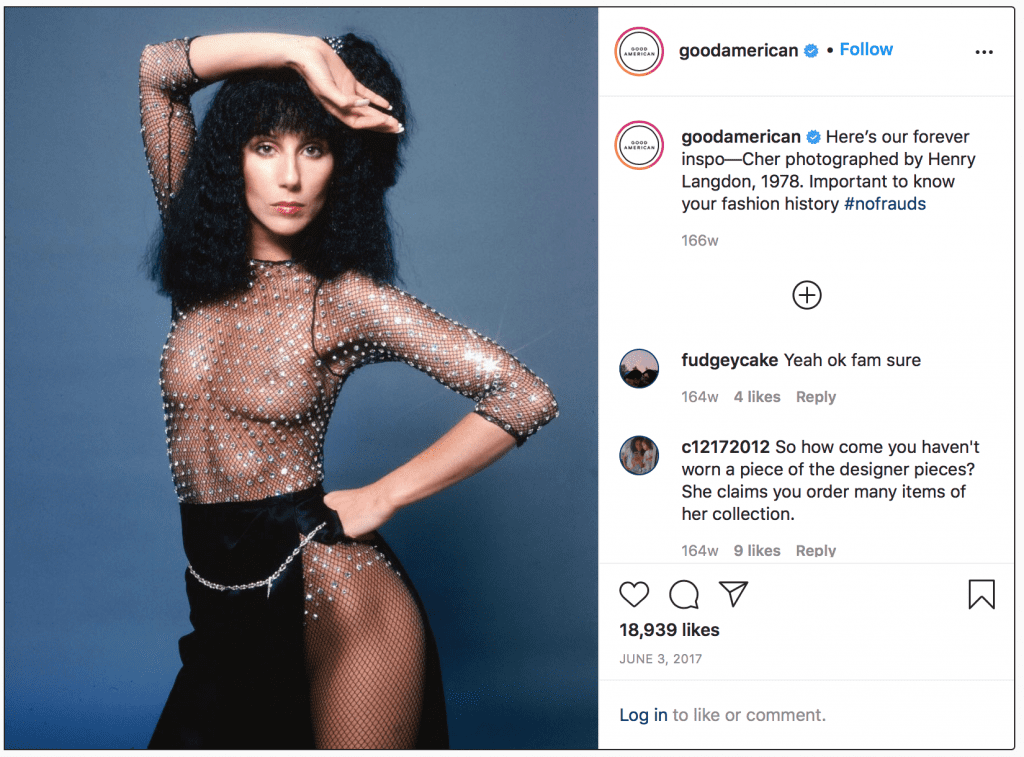

In terms of the statements, themselves, the first is an official statement from Good American – which asserted in a June 2017 article published by Cosmo in connection with dbleudazzled’s public claims that Kardashian and her brand copied her distinctive bodysuits – that “under no circumstances did Good American or Khloe Kardashian infringe another brand’s intellectual property.” The second “statement” comes in the form of June 2017 Instagram posts of images of Cher, Diana Ross and Britney Spears in crystal embedded tops along with the language, “Important to know your fashion history #nofrauds,” “Vintage Diana Ross. Showgirl vibes. #inspo” and “Britney in Toxic #inspo,” in reference to allegations that they were inspired by/infringed dbleudazzled’s trade dress in embellished bodysuits.

Finally, in the third statement, Kardashian suggested in a June 2017 Instagram post, in which she announced the launch of the Good American bodysuit collection, “that she came up with the designs for [the allegedly copycat] bodysuit over the course of almost a year, when in reality,” dbleudazzled claims, “she spent several months ordering [dbleudazzled’s] bodysuits and copying those designs.”

Taken together, these statements – which were made in a “public forum in connection with an issue of public interest,” and which served the purpose of Kardashian and Good American “publicly defending themselves against the plaintiff’s widespread, fallacious media attacks” – serve as the foundation for dbleudazzled’s unfair competition claims, which is why the defendants argue that California’s anti-SLAPP statute applies. Here, the “public forum” is Instagram and Cosmo magazine, and the matter of “public interest” because Kardashian, herself, is a “media superstar,” and her “statements concerning their clothing design’s originality communicated information of interest both to Good American consumers and to Kardashian’s vast fan base.”

With the foregoing in mind, the defendants assert that “public statements about well-known individuals are inherently matters of public interest, and therefore constitute protected speech for purposes of the first prong of the anti-SLAPP analysis,” particularly given “California’s broad standard for defining ‘an issue in which the public is interested.’”

Proving Copying

From a procedural perspective, if a defendant can show that a plaintiff’s cause of action arises from protected activity, such as “constitutionally protected speech” that is “clearly a matter of public interest,” which is presumably what Kardashian and Good American have done, the burden in the anti-SLAPP analysis shifts to the plaintiff, who must then establish “a probability that the plaintiff will prevail on the claim.” In this case at hand, that would mean that dbleudazzled would have to produce “admissible evidence showing that the defendants were lying about the inspiration for the bodysuits and that members of the public were likely to be deceived” by such lies.

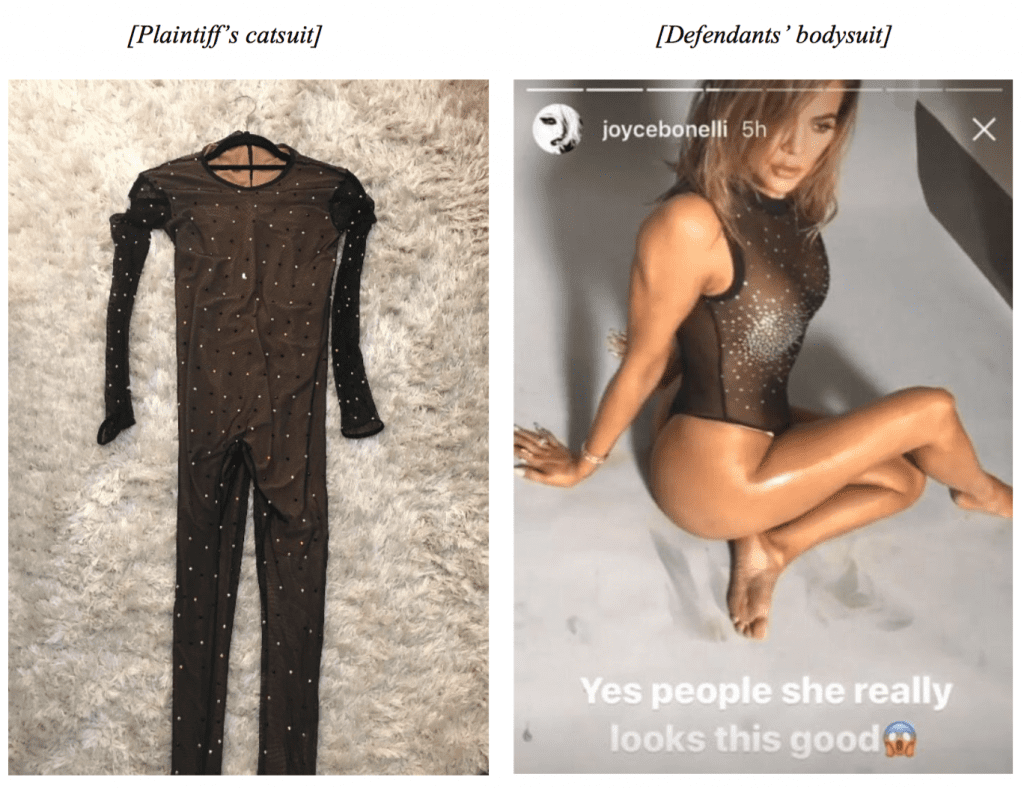

In terms of proving copying, there are at least a couple of significant factors at play, according to Kardashian and Good American. For one thing, despite dbleudazzled’s “complaint misleadingly alleging that Kardashian received a bodysuit from” the company, that is not the case. Instead, dbleudazzled – which is hardly an unknown name in the fashion world, with fans ranging from Beyonce (whose recently-released “Black is King” visual album is smattered with the brand’s wares) and Rihanna to Mariah Carey and Lady Gaga – sent “bras, fishnets, leggings, socks, shorts and panties,” as well as “catsuits to Kardashian’s stylist.” The design of catsuit, itself, they argue “is completely different from the design of the bodysuit at issue and cannot, as a matter of law, be deemed the basis for a copying allegation … as the dbleudazzled catsuits simply look absolutely nothing like the bodysuits created by Good American.”

Moreover, the defendants argue that dbleudazzled will have a hard time proving copying because while the company “suggests there is something unique in its bodysuit and/or ‘nipple burst’ design [on its bodysuit], neither is true.” In fact, the defendants claim that “early examples of tight-fitting crystallized tops and bodysuits date back to the flashy outfits of Las Vegas showgirls and other performers in the 1920’s” and “have also been worn in more recent popular culture by performers and artists such as Marilyn Monroe, Cher, Diana Ross, and Britney Spears.”

“In short, given its existence in popular fashion for decades, dbleudazzled cannot possibly claim that the look of a bedazzled bodysuit concentrating crystals around the bust area was in any way ‘created by’ [dbleudazzled] or was unique trade dress feature,” Kardashian and Good American assert.

Against this background, and given that dbleudazzled “cannot show that the defendants copied its designs (the defendants did not) and certainly cannot show that any of the defendants’ public statements were false or misleading to consumers,” Kardashian and Good American argue that dbleudazzled will not be able to meet “its burden of demonstrating a probability of prevailing on the merits” in connection with the anti-SLAPP motion.

The defendants argue that they are not only “permitted to publicly defend themselves from the plaintiff’s media attacks and speak to their wide audience about the sources of their inspiration for the design of their clothing line without interference from the plaintiff,” but that the court “can readily conclude as a matter of law that there is no representation (much less misrepresentation) in the above [statements] about the origin or design of the bodysuits.” As such, counsel for Kardashian and Good American assert that dbleudazzled’s unfair competition claims are subject to a special motion to strike under the anti-SLAPP statute.

“Smear Campaign”

While the motion does not speak at length about dbleudazzled’s trade dress infringement claims, the defendants do allege that the brand lacks legal grounds on that front (and that the lawsuit, as a whole, is “entirely without merit”). According to the filing, before dbleudazzled initiated the lawsuit at play, its founder Destiney Bleu “launched an all-out media campaign, accusing the defendants of copying her work in major media outlets despite the fact that her attorney proclaimed that she had no basis for any legal action.”

The defendants cite a June 8, 2017 letter from the plaintiff’s counsel to the defendants’ counsel, in which the plaintiff “threatened that Kardashian ‘will rightly face judgment in the court of public opinion’ even though ‘copying clothing and fashion is generally not intellectual property infringement.’” In that same letter, the plaintiff’s “counsel admitted, ‘It is not illegal for [the defendants] to copy [the plaintiff’s] designs.’” Despite such an alleged lack of legal rights in the design, Kardashian and Good American claim that dbleudazzled “deliberately engaged in a widespread smear campaign precisely because [it] knew that it had no legitimate legal claims against the defendants.”

A hearing on the Special Motion to Strike is scheduled for September 25.

*The case is dbleudazzled, LLC v. Khloe Kardashian and Good American, LLC, 20STCV20510 (Cal.Sup.).