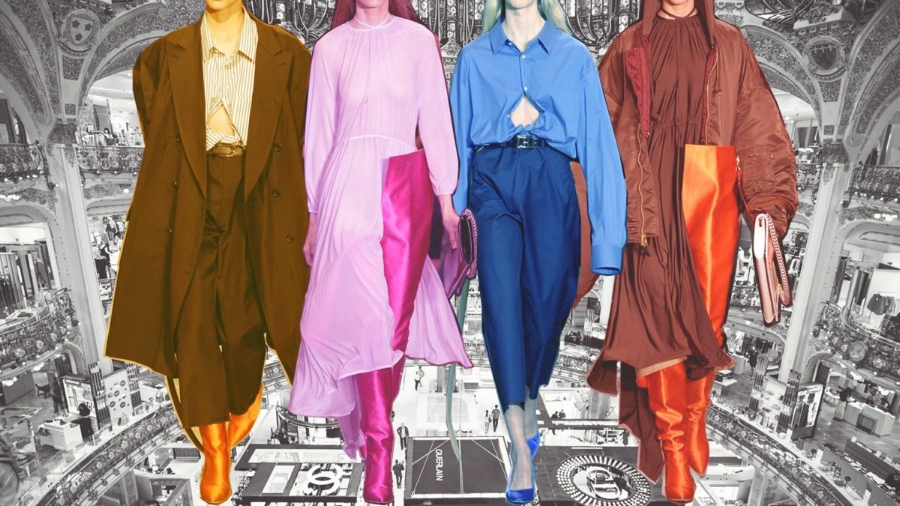

image: yoyokulala

Most fashion brands are privately held companies exempt from required public disclosures of revenue and profitability. As a result, it is difficult – if not nearly impossible – to gauge which brands are thriving (à la Thom Browne, which recently made headlines in connection with its burgeoning business) and which are on the verge of a “hiatus,” as Hood by Air so poetically worded its shuttering in April.

With a lack of uniformity in terms of many brands’ business models and without publicly-available revenue reports to reference and the ever-present amount of marketing efforts (and often larger-than-life social media presences) surrounding our favorite brands, how do we know which brands will go the way of Hood by Air, SUNO, Vena Cava, Meadham Kirchhoff, Reed Krakoff, Honor, Thomas Tait, and other once-seemingly-thriving and now-defunct fashion labels?

In short: It is difficult. As Steven Kolb, the CEO of the Council of Fashion Designers of America told fashion publication Vestoj last year, this is compounded by fashion’s distaste for discussing the fact that the actual health of fashion companies. “There’s a lot of smoke and mirrors in this industry. It’s hard to tell how well a fashion business is doing: whether people are getting paid, what a company’s cash flow is like,” he said. Consultant Jean-Jacques Picart echoed this notion, saying, “In fashion we treat failure as if it was a disease.”

Things are further complicated by the fact that at different tiers of the upper echelon of the fashion industry, alone, brands tend to operate in accordance with markedly different models – making it difficult – at times – to differentiate between money-making activities and ones put into action purely for marketing purposes.

How Do Brands Really Make Money?

Since it is no easy feat to determine which fashion brands are thriving and to what extent they are profitable, the question becomes: How are existing brands actually making money?

The revenue structures of the industry’s truly established fashion and luxury brands are somewhat clear-cut. Brands that boast portfolios of world-renowned intellectual property (namely, trademarks) to rely on are often profitable, largely due to their affordable licensed (or sometimes in-house produced) goods, such as cosmetics and fragrances, jewelry collections, and eyewear. House-made small leather goods often prove hugely profitable for these brands, as well.

Brands, such as those under the umbrellas of LVMH (think: Louis Vuitton, Givenchy, Celine, Loewe, and Pucci, among others) and Kering (Balenciaga, Yves Saint Laurent, Gucci, etc.), whose names and logos – aka their trademarks – enjoy widespread recognition amongst consumers, and as a result, they can slap their marks on lower-priced goods and profit handsomely.

This is because most consumers can much more easily afford a fragrance or pair of sunglasses as opposed to a $5,000 dress or bag – and they often seek out such purchases in an attempt to own something from one of these coveted luxury brands. Chanel, for instance – a privately owned brand – reportedly brings in 60 percent of its revenue from cosmetics alone. Most of the other 40 percent is likely coming from the sale of its coveted bags.

At the moment, one of the top-selling products for Givenchy, on the other hand, is lipstick – not its pricey runway garments. This is nothing if not indicative of a larger trend. If recent trademark filings by the industry’s top conglomerates are any indication, cosmetics are the future – as of now, at least. The majority of trademark applications that LVMH filed between 2012 and 2016, which totaled almost 7,000 applications, specifically specified “use [of the mark] in connection with perfumes.” Perfume was also a top concern for Kering, which filed nearly 3,000 trademark applications between 2012 and 2016 for marks to be used on perfumes.

There are exceptions, of course. The Marc Jacobs brand, for instance, which is owned by LVMH, despite its beauty and eyewear licenses, has reportedly struggled in recent years. As the New York Post reported in 2015, “All is not well in the house of Marc Jacobs.” This was followed up by a statement a couple of years later by LVMH chairman Bernard Arnault, who famously said he is “more concerned about Marc Jacobs than the U.S. president.”

None of this amounts to earth-shattering news, though. It is hardly a secret that runway looks rarely comprise a significant portion of profitable brands’ revenue streams, and that secondary goods – more often than not – are the cash cows. Both small leather goods and cosmetics are sold off at high margins, after all, and thereby enable these brands to profit significantly from their sale.

Aside from cosmetics, secondary diffusion lines (à la Balmain with its more affordable little sister line, Pierre Balmain, and Maison Margiela with its MM6 collection) have also contributed to the profitability of high fashion brands. It is worth noting that as of late, this is something of a dying art, as indicated by the many diffusion line closures over the past several years, including but not limited to Marc by Marc Jacobs, Dolce and Gabbana’s D&G line, and Sonia by Sonia Rykiel.

Younger Brands: A Different Ball Game

A step down the totem pole finds us in the ranks of younger labels that are established but rarely owned by luxury conglomerates. This category ranges from the Proenza Schoulers, Alexander Wangs, and Rodartes to the slightly younger Marques’ Almeidas, Vetements, and Jacquemuses. And this is where it becomes increasingly difficult to determine just how well brands are actually doing.

The range of potential profitability within this seemingly small sect is striking: Not too long ago, Proenza Schouler’s rumored acquisition by LVMH was put to bed – according to a lawsuit filed by former Proenza CFO Patrice Lataillade – because the brand simply was not profitable enough. Fellow New York-based brand Altuzarra, on the other hand, welcomed a minority investment from Kering in 2013. The range is wide.

There are, of course, the labels that make money from their own collections (and not licensed goods), but it is largely from accessible goods. “It” brand Vetements is likely sustaining itself thanks to fanfare (read: sales) resulting from an early co-sign from rapper Kanye West and a whole lot of t-shirts and sweatshirts being bought up in Asia and fashionable circles in the U.S.

This is not terribly unlike how the now-defunct Hood by Air operated. For many years it seemed the only thing that actually made it onto the backs of consumers was the brand’s bold HBA graphic t-shirts and maybe a handful of sweatshirts.

Still yet, consider Moschino, which is much older than the two aforementioned brands. Under Jeremy Scott, the Italian brand sells a sizable amount of affordable house-made items, such as t-shirts and sweaters, iPhone cases, and the like. It also boasts eyewear and fragrance licenses to help pick up the slack.

External Sources of Cash

But what about some of the relatively young (i.e. just over 10 years old) privately-owned labels like Alexander Wang and Rodarte? These are two interesting examples, as these brands almost certainly look outside of their main collections – their runway collections – for most of their revenue streams.

In addition to its more affordable T by Alexander Wang collection, Alexander Wang has booked various collaborations to rake in cash. The New York-based brand teamed up with Swedish fast fashion giant H&M in 2014, thereby bringing in a pay check in the ball park of an estimated $1 million dollars. Moreover, Wang has signed on with adidas for another lucrative collab, which has seen two collection drops since its debut in 2016. The brand has also put its name on collaborations with Evian and Beats by Dre.

Rodarte operates according to a similar model. The Los Angeles-based brand – which has been praised for its “couture-like” creations (think: $21,000 mermaid-inspired dresses) – almost certainly makes most of its money from its “Radarte” line of track pants, t-shirts and sweatshirts (something its PR team has – obviously – denied, saying the brand sells quite a bit of its Ready-to-Wear and ALSO has experienced “strong growth in more accessible items including T-shirts and sweatshirts”).

Nonetheless, the number of other projects that the Rodarte founders and creative directors, Kate and Laura Mulleavy, are involved in suggests that their outside consulting likely funds their Rodarte design activities. In the past few years alone, Rodarte has lent its name and design sensibilities to Coach, Oliver Peoples, & Other Stories, and the Rug Company, among brands.

Additionally, according to Rodarte’s website, “The [Mulleavys] have collaborated on special projects with Frank Gehry and Gustavo Dudamel on the LA Philharmonic’s production of Don Giovanni; Benjamin Millepied on costumes for the New York City Ballet’s Two Hearts and L.A. Dance Project’s Moving Parts; and Catherine Opie and Alec Soth on Rodarte, Catherine Opie, Alec Soth, their first monograph.” They have also collaborated with Todd Cole on a short film, entitled, “This Must Be The Only Fantasy.” And recently directed a feature film, entitled, “Woodshock.”

Note: This is not terribly unlike the significant amount of consulting that occurs in the industry. Before becoming creative directors for Oscar de la Renta, Laura Kim and Fernando Garcia worked for some time in consulting capacities for the brand, while also maintaining their fledgling Monse brand. Wes Gordon is another example; he is currently consulting for Carolina Herrera in addition to running his own label.

Finally, it is also important to consider the role of off-price retailers, such as TJ Maxx, Marshalls, and Saks’ Off-5th chain, when determining exactly where fashion companies are making their money. While many brands stock at upscale outposts, such as Bergdorf Goodman, Neiman Marcus, Bloomingdales, Saks, etc., they stand to potentially make even more money from sales at Century 21 and similarly situated retailers, where they can (and often do) off-load unsold merchandise at the end of a season.

(Note: In many cases, department stores’ distribution contracts require brands to buy-back unsold merchandise after a certain amount of time, which oftentimes leads to brands selling old stock to discount retailers instead, where no such requirements are in place).

In short, most fashion brands make money. The question is: How much is actually coming from the sale of their own branded items and how much is coming from external projects? It remains difficult to gauge just how well individual brands are doing given the number and range of projects in which their creatives are involved, and the industry’s pattern of shying away from discussion regarding brand vitality.

Nonetheless, it is safe to say that for the vast majority of brands, their creative endeavors (read: runway looks and main collections) are not a gold mine, and it is, instead, the array of outside jobs – whether it be collaborations or quieter/more under-the-radar consulting – are where the real money is … along with accessories, of course.

Right now, particularly in light of the ever-shifting consumption patterns of fashion/retail consumers, there is no real blueprint for vitality or set-in-stone definition of success (unless you are Zara and can produce on-trend garments for dirt-cheap prices and on a wildly fast timetable). While brands may have once been able to sustain themselves purely by selling full-priced, season-specific garments, that does not appear to be the way – at least right now.

As such, brands are forced to diversify. The balance of traditional brand-specific activities and consulting/collaborations/outside projects seems to be what is indicative of a successful brand … because as Mr. Kolb said, “Going out of business, that’s failure. Not being able to deliver what you promise, not being able to pay your employees, not being able to feed the infrastructure you’ve created – that’s failure.” Everything else is just a way to make it work.

(Editing by Nicole Malick)