In non-metaverse Nike news, John Geiger Collection (“Geiger”) wants out of the lawsuit that Nike filed against it this summer, arguing that the Beaverton, Oregon-based sportswear behemoth has failed to make a case against it for allegedly infringing its famed Air Force 1 trade dress by way of lookalike sneakers. The case first got its start in January when Nike filed suit against footwear manufacturer La La Land Production & Design, and then added Geiger as a defendant in an amended complaint in August, in which Nike argues that La La Land and customer John Geiger are on the hook for trademark infringement and dilution, as both of the defendants have “intentionally created confusion in the marketplace by, among other things, using Nike’s Air Force 1 trade dress.”

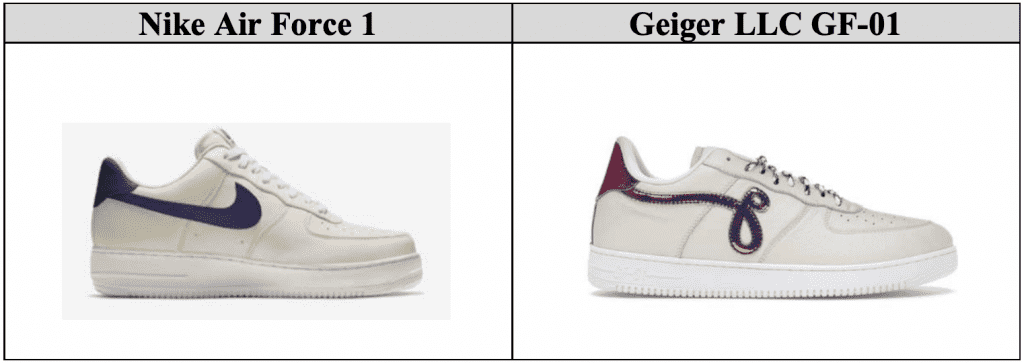

In its amended complaint this summer, Nike asserted that during the course of discovery in connection with the case it filed against La La Land, it learned that the footwear company had manufactured “at least one [style] of John Geiger’s so-called GF-01 shoes,” which bear Nike’s “Air Force 1 trade dress and/or confusingly similar trade dress” and which are sold “in the identical channels of trade and to identical consumers as Nike’s genuine products.”

On the heels of Nike adding it to the existing trademark infringement and dilution case, the Los Angeles-based John Geiger brand is arguing that Nike falls short on its trademark claims, including the critical element of whether consumers are likely to be confused about the nature of Geiger’s “lookalike” sneakers, namely, whether Nike is in some way affiliated with – or approved – them, and thus, Geiger that a California federal court should dismiss Nike’s claims against it once and for all.

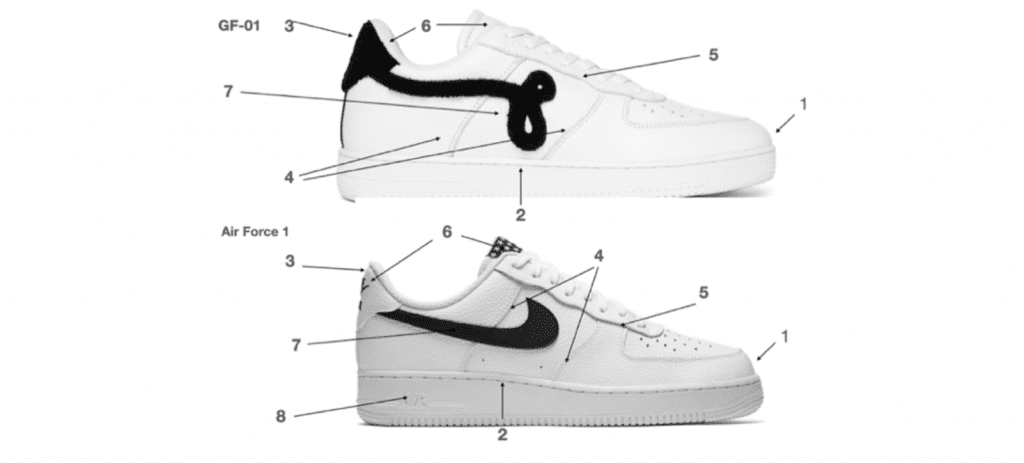

At the heart of Geiger’s October 2 motion to dismiss is its argument that Nike fails to state any claims upon which relief may be granted, namely, because it fails “to make a plausible showing of likelihood of confusion.” Setting the stage, John Geiger states that if you “ask anyone in the world how to spot a Nike, they will tell you: look for the Swoosh,” a nod to the fact that “the Swoosh is emblazoned on every Air Force 1 sneaker that Nike has ever sold.” Despite Nike’s consistent use of the source-identifying Swoosh logo on its AF1 styles, and the lack of a Swoosh on Geiger’s allegedly infringing the GF-01 sneakers, Geiger says that “Nike asks this Court to believe that … the GF-01 is somehow likely to cause confusion with the Air Force 1—even though the GF-01 prominently features Geiger’s own housemark, its signature ‘G’ logo, which looks nothing like the Swoosh.”

Against that background, and with a comparison of the Geiger GF-01 and Nike Air Force 1 sneakers in mind, Geiger argues that Nike is “unable to plausibly allege a likelihood of confusion,” which is a foundational element in a viable trademark infringement claim. “Nike’s inability to demonstrate a likelihood of confusion between these two sneakers eviscerates its case against Geiger,” the defendant argues.

Additional elements – such as the difference in price between the two parties’ sneakers at retail (Geiger’s GF-01 sell for $220.00, while the Air Force 1 “typically retails for only $90”); the different positioning of the sneakers (Geiger argues that his are “luxury fashion sneakers,” whereas Nike’s “originated as basketball shoes”); and the “high degree of care” that its “savvy ‘sneakerhead’ consumers are likely to exercise in purchasing the sneaker through its exclusive distribution channels” – also weigh against a likelihood of confusion, according to Geiger.

Distinctiveness – or Lack Thereof?

John Geiger goes on to point to another allegedly fatal flaw in Nike’s case: “The trade dress elements that Nike claims that Geiger infringed – things like the stitching that holds the sneaker together – are primarily functional, and lack the distinctiveness required to obtain a trade dress registration in the first place.” While the defendant acknowledges that the Swoosh logo is “undoubtedly the most distinct source identifier of Nike’s sneakers,” it argues that “Nike does not sufficiently allege that the Air Force 1 trade dress on its own would serve the same purpose.” (Emphasis added by TFL here.)

In fact, Geiger states that “the generic elements that Nike claims as its Air Force 1 trade dress” – including the designs of “the material panels that form the exterior body of the shoe; the wavy panel on top of the shoe that encompasses the eyelets for the shoe laces; the vertical ridge pattern on the sides of the sole of the shoe; and the relative position of these elements to each other” – have “little to no ‘source-identifying function,’” making it so that the shoe design, itself, sans the Swoosh, is not protectable as a trademark.

“Nike may argue that consumers already associate the elements of the [two cited trade dress] registrations with the Air Force 1″ (no. 3,451,905 and 5,820,374), but Geiger claims that consumers have “never had an opportunity to form that association because they have never seen the trade dress standing alone without a Swoosh stitched on top of it, and Nike has never marketed an Air Force 1 without the Swoosh.” More than that, Geiger asserts that Nike “has not pled the existence of a pair of Air Force 1’s that do not also display its Swoosh mark.”

Even if the various elements of the AF1 sneakers – without the Swoosh – have acquired the requisite level of distinctiveness to act as an indicator of the source of the sneakers, Geiger claims that Nike still falls short, as “that distinctiveness has been erased by Nike’s failure to police the growing number of brands over the past two decades – including Wal-Mart, A Bathing Ape, Yums, Kappa, Hender Scheme and Gab3 – that sell sneakers embodying the exact same elements Nike claims are intrinsic to the Air Force 1.” Asserting that a trademark holder’s “failure to prosecute other infringers is relevant to determining the strength of the mark for purposes of the likelihood of confusion analysis,” Geiger contends that Nike’s “failure to enforce its alleged Air Force 1 trade dress has significantly weakened the strength of [its] registrations by virtually eliminating their distinctiveness.”

And still yet, Geiger argues that there is yet another issue with Nike’s AF1 trade dress. “Nike frequently markets Air Force 1 sneakers that deviate from the very trade dress Nike seeks to enforce here,” per Geiger, which “undermines and weakens [the] strength and distinctiveness” of the trade dress.

In light of such an alleged lack of potential confusion among consumers, and given that Nike’s claimed trade dress “lacks distinctiveness and the registrations themselves fail to demonstrate non-functionality,” Geiger argues that Nike fails to sufficiently set out claims trademark infringement and unfair competition claims. Geiger also takes issue with Nike’s move to join it in the lawsuit that was previously filed against La La Land, and argues that because “the claims asserted against [it and La La Land] do not arise from the same occurrences or transactions and lack any common questions of fact or law, and because requiring John Geiger Collection LLC to proceed in this action is fundamentally unfair,” the court should “sever [Nike’]s claims against [it] for misjoinder” if it does not otherwise dismiss the claims.

In its amended complaint, Nike argues that both “La La Land and John Geiger have taken systematic steps in an attempt to falsely associate [their] infringing products with Nike,” and have “attempted to capitalize on Nike’s valuable reputation and customer goodwill” by using its Dunk and Air Force 1 trade dress, as well as its iconic Swoosh logo, “in a manner that is likely to cause consumers and potential customers to believe that the infringing products are associated with Nike, when they are not,” the sportswear titan claims.

Part of the problem, according to Nike stems from the fact that while the allegedly infringing sneakers at issue mirror its own designs, it “has no control over the nature and quality of the infringing products that the defendants offer.”

With such a lack of oversight in mind, Nike says that its “reputation and goodwill will be damaged – and the value of [its] trademarks jeopardized – by the defendants’ continued use of [its] marks and/or confusingly similar marks,” presumably in sales conditions and/or product quality that differ from Nike’s. For instance, Nike claims that it “maintains strict quality control standards for its products bearing [its] marks,” with its products “inspected and approved by Nike prior to distribution and sale.” Additionally, it “maintains strict control over the use of [its] marks in connection with its products so that Nike can maintain control over its related business reputation and goodwill,” including by “carefully determin[ing] how many products bearing [its] marks are released, where the products are released, when the products are released, and how the products are released.”

The case is Nike, Inc. v. La La Land Production & Design, Inc., 2:21-cv-00443 (C.D. Cal.)