“Fashionistas are clamoring to get their hands on a ‘Walmart Birkin,’ also known as a “Wirkin,” the New York Post reported this weekend, referring to an inexpensive handbag that looks a whole lot like Hermès’ most coveted offering. Ranging from $78 to $102 depending on the size of the bag, the “Walmart Birkin” has garnered viral status online so much so that it has sold out on the retail giant’s site on more than one occasion. TikTok users and the media, alike, have been quick to label the bag a “dupe,” a term that typically refers to legally-above-board products that replicate the look of high-priced goods — sans any legally-protectable elements. But is the “Walmart Birkin” actually in the clear from a legal point of view? Probably not.

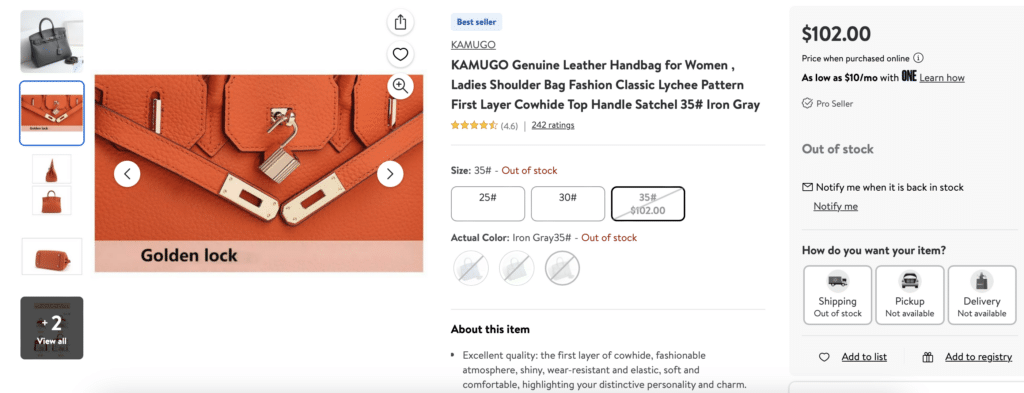

One version of the Birkin bag that is being offered up on Walmart’s e-commerce marketplace (via a third-party seller) does not make use of Hermès’ name on the bag, itself; on a real Birkin, Hermès’ name appears on the body of the bag underneath the flap, inside the bag, and on various hardware. At the same time, the discount replica also does not copy Hermès’ trademark-protected “H” logo, which appears on the lock on an authentic Birkin bag. Still yet, the listing for the “Genuine Leather Handbags Purse for Women Tote Shoulder Bag” from a third-party seller called KAMUGO, for example, does not make use of the Hermès name or “Birkin” word mark.

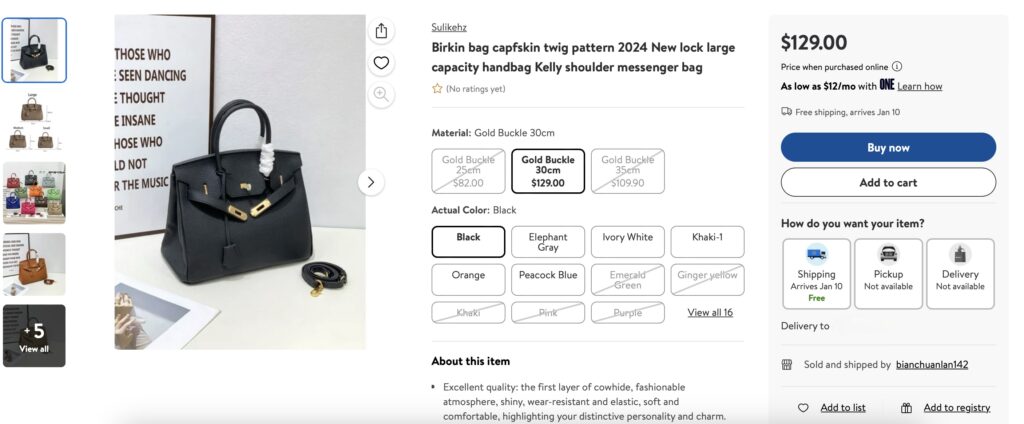

> Other offerings, such as one from third-party company Sulikehz, make use of the “Birkin” and “Hermès” word marks, giving rise to potential trademark issues.

The KAMUGO-made bag and others like it are almost certainly still running afoul of the law because the look of the Birkin bag, itself, is protected – with or without the inclusion of the Hermès word marks. Yes, in addition to its rights in the BIRKIN name, Hermès has a monopoly of sorts in the distinctive shape of the bag. In other words, Hermès has rights in the Birkin bag trade dress, which consists of …

“The configuration of a handbag, having rectangular sides a rectangular bottom, and a dimpled triangular profile. The top of the bag consists of a rectangular flap having three protruding lobes, between which are two keyhole-shaped openings that surround the base of the handles. Over the flap is a horizontal rectangular strap having an opening to receive a padlock eye. A lock in the shape of a padlock forms the clasp for the bag at the center of the strap” … for use on handbags.

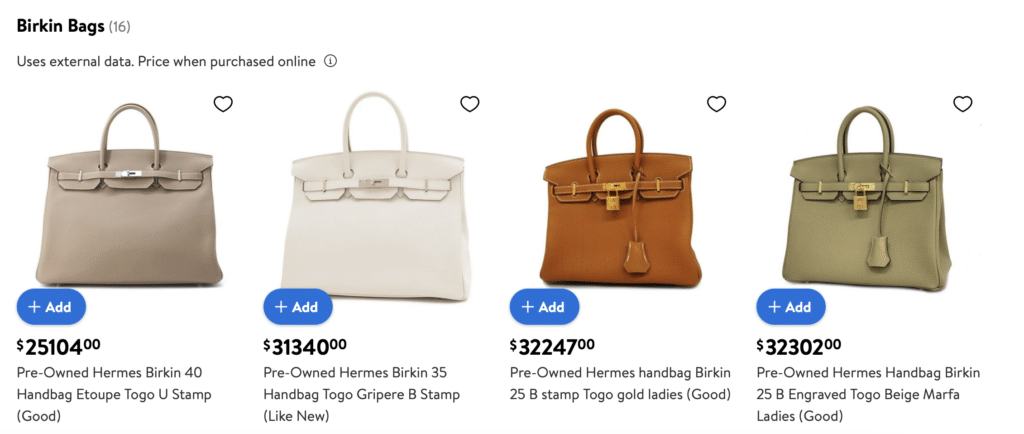

With the foregoing in mind, the question becomes one of confusion. If Hermès were to wage a trademark infringement claim against KAMUGO (the company behind the bag) for offering it up for sale and selling it and Walmart for facilitating its sale, the critical inquiry would be whether consumers are likely to be confused about the source of the handbag and/or Hermès affiliation/endorsement of the bag in light of its near-exact appearance. There are several factors that would weigh in Hermès’ favor in such an analysis; in addition to the strength of the Hermès’ Birkin trade dress and the obvious intent to trade on the appeal of/demand for the Birkin bag, there is the fact that third-party sellers offer up purportedly authentic Birkin bags on Walmart’s marketplace.

A quick search of the e-commerce platform reveals that dozens of potentially authentic, pre-owned Birkins are available for purchase for price tags of $15,000-plus. This could enable Hermès to bolster its as-of-now-hypothetical trademark infringement claim by arguing that consumers are more likely to be confused given that there are (potentially) authentic Hermès bags available on Walmart’s site.

On the flip side, Walmart and the third-party sellers could highlight the eye-watering difference between the price tags of the allegedly infringing bags ($100 or less for) with the price tag of real ones, which routinely sell for $10,000 or more on the secondary market, to maintain that consumers are unlikely to confuse the two. In addition to the very-different prices of the bags, the hypothetical defendants could probably also argue that the marketing and distribution channels for real Birkin bags and the allegedly infringing ones are very different, weighing against the likelihood of consumer confusion. It is here that Hermès could counter, at least in part, and point to the robust resale market for its most sought-after bags and the resulting lack of clear lines between formerly distinct distribution channels.

Regardless of the outcome of an infringement claim, Hermès would also have a dilution cause of action on its hands given the level of fame of its Birkin bag trade dress. As distinct from trademark infringement, which centers on likelihood of confusion, a trademark dilution claim enables the owner of a truly famous mark to bar unauthorized use of that mark regardless of whether consumers might be deceived about its source in order to prevent a lessening of its distinctiveness or tarnishing of the goodwill associated with the mark.

Chances are, in the wake of the widespread media attention to the fake Birkins being offered up on Walmart’s marketplace, the listing will disappear. Hermès will undoubtedly initiate takedown proceedings with Walmart. As for whether it will take action against the individual sellers, many of which appear to be based on China, and/or Walmart, to prevent future sales and/or seek damages, stay tuned.