The International Trademark Association released a metaverse-centric white paper this week aimed at providing “an introduction to the metaverse and the diverse problems and issues that its development may cause for brand owners.” Setting the stage, INTA asserts that the metaverse “currently does not identify a single shared virtual space,” but is spread “across various platforms, and therefore, can only come into full existence once there is a true interoperability between these different platforms.” In light of its relative nascency, INTA states that the metaverse is “causing the legal community to re-think, again, many of the same issues that it had to address in the late 1990s and early 2000s, on how the interactive and decentralized version of the Internet will affect daily lives.”

In addition to encouraging the intellectual property community to broadly “consider how [the metaverse] will affect brand owners and the proper way to address the challenges that it will bring about,” INTA’s New Emerging Issues Subcommittee claims that are a slew of critical issues at play – from the need to “harmonize classification of trademarks for metaverse activity and digital assets” to the “lack of certainty for trademark holders that under a traditional zone of expansion analysis, a court would find that virtual goods are in the natural zone of expansion of their physical world counterparts.”

INTA also points to looming questions over “how licensing practices should adapt to the metaverse landscape as [the metaverse’s] development evolves” and the “unique barriers to successful counterfeit detection and enforcement of trademarks, design rights, and trade dress that exist in the metaverse, including the difficulty in identifying infringers and establishing court jurisdiction.”

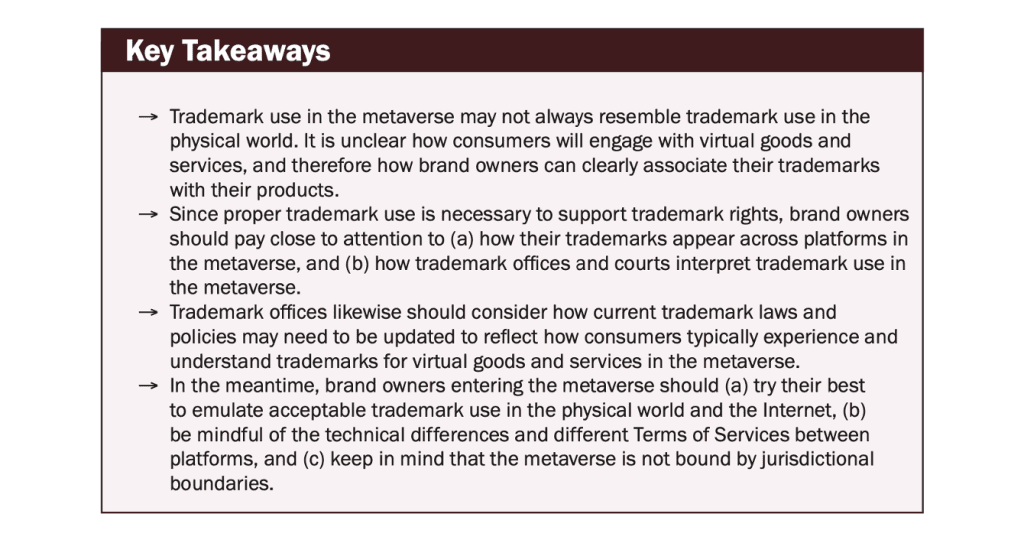

The full white paper can be found here, and we have highlighted some key takeaways below …

The role of existing TM registrations – “One of the main questions faced by existing brands is whether their pre-existing trademark registrations for physical goods are sufficient, or if it is necessary to apply separately for [registrations] for virtual counterparts,” INTA asserts. If a brand “does not file applications for virtual goods or does not create virtual goods, could it be superseded by the metaverse equivalent of a cybersquatter? Or will tribunals enforce preexisting rights in physical world goods in the metaverse?”

These questions have been tentatively answered at least once in favor of expanding pre-existing “real” world rights into the metaverse, INTA says, citing the Hermès v. Rothschild case, which is “one of the first cases ever filed applying pre-existing trademark rights in physical-world goods to the virtual world.” Ahead of a jury returning a verdict in favor of Hermès in February, INTA notes that the district court denied Rothschild’s motion to dismiss, thereby, “recognizing that Hermès’ [trademark infringement and dilution] claims could have merit” even if it is not actively using the “Birkin” word mark or trade dress in the metaverse and does not maintain registrations for those marks in the quintessential metaverse classes of goods/services.

(TFL noted last year that the court’s order seemed to suggest that the trademark rights that brands have amassed for use on purely physical goods – and “real” world services – could very well extend into the metaverse and allow for successful infringement claims.)

The present outcome in the MetaBirkins case “arguably follows a simple logic that trademark attorneys have seen play out in comparable situations: Where the value of a virtual good is derived from its physical-world value, it only makes sense for the physical-world owner to reap the benefits,” INTA states. From a policy perspective, “it would make little sense for courts to punish existing brand owners by permitting third parties to use sales of digital images of recognizable goods to profit from the pre-existing goodwill developed by sales of the physical goods shown in the images.”

As such, INTA says that it would “make sense for tribunals to exercise flexibility when tasked with determining whether owners of trademarks for physical goods can enforce their rights in the metaverse without additional registration or use of a mark that is specific to the metaverse, [and] the same may hold true for preexisting shape trademarks and trade dress where sufficient evidence of secondary meaning can be established.”

An additional issue on this front: Questions remain about how tribunals will handle the case of brands that exist solely in the metaverse enforcing their marks for virtual goods against use of the mark for physical world counterparts, per INTA. “For example, should a non-famous brand that sells virtual clothing only in the metaverse be able to successfully demand that a small clothing boutique operating under the same mark and that has never had a presence in the metaverse cease and desist use?” As this example illustrates, the metaverse will present new questions related to both likelihood of confusion and zone of expansion that courts will need to grapple with.

Trademark use in the metaverse – In terms of use, INTA provides a few key takeaways …

The what, how & where of filing – Early examples – both from the MetaBirkins case and from USPTO Office actions (including in response to unauthorized/unaffiliated applications for registration for the GUCCI and PRADA word marks for use in the metaverse) suggest that additional registrations may not be necessary for well-known brands. However, questions remain for trademark holders that opt to file new applications for registrations for web3 uses (and no shortage of companies have). “The metaverse, much like the Internet, is not restrained by geographical boundaries,” per INTA, and therefore, “by placing a brand into the metaverse, a brand owner arguably enters international commerce. This is all the more true if we take interoperability as an essential feature of the metaverse, so that use would not be restricted to some particular platform or depend upon a specific service provider.”

Trademark offices appear to agree that “most virtual goods belong in Class 9,” according to INTA. However, whether that is “the most prudent strategy is yet to be determined.” In terms of guidance, the USPTO “has indicated that it will reject identifications that attempt to claim virtual goods in the class of their physical world counterparts,” with INTA pointing to Yuga Labs LLC’s initial application for the mark BA YC for “digital collectibles; digital collectibles sold as non-fungible tokens” in Class 16, presumably because Class 16 is the appropriate class for physical world paper collectibles, such as trading cards. In a non-final office action issued in March 2022, the USPTO examiner stated that Class 16 is for printed and paper goods and suggested that Yuga amend the identification to Class 9.

As for where companies should be filing new applications, “those that already operate online seemingly would not need to reinvent the wheel regarding their global strategy and should continue to focus clearance and filing resources on important jurisdictions, e.g., key consumer markets, key places for production of goods, and/or other places where piracy justifies additional prophylactic steps.” INTA states that “it is worth noting that new metaverse-based consumer interactions could open up previously unforeseen markets for a trademark, and accordingly, it would behoove brand owners who are active in the metaverse to be reasonably attentive to new market penetration with consumers and pirates in the metaverse, as this information could impact which jurisdictions are deemed important for protection.”

Infringement claims – Reflecting on metaverse-specific trademark infringement claims, INTA states that the primary challenge appears to be establishing that “the infringement has taken place in the course of trade, and, at least in the U.S., potentially having to balance the trademark owners’ rights with a third-party user’s First Amendment rights.” A preliminary issue in some jurisdictions will be “whether use of a brand outside of a commercial transaction (such as on wallpaper or on an avatar’s free clothing) will satisfy the requirements for use in the course of trade or use in commerce,” according to INTA. And even if this preliminary use threshold is met, “the similarity of the goods on which the parties’ use the marks may be an issue. For example, if consumers encounter a brand on virtual goods, will they believe the virtual goods to be authorized by a trademark owner who sells only corresponding physical goods with the same brand? What if the trademark owner does not offer corresponding physical goods?”

Jurisdiction may also give rise to issues. Regarding trademark infringement claims arising from the metaverse, which like the Internet itself, by definition is “borderless,” INTA notes that “courts will continue to look to the facts of the particular case to determine whether a defendant has sufficient ‘minimum contacts’ in a forum to establish personal jurisdiction.”

Non-fungible tokens – Not limiting its focus exclusively to the metaverse/virtual goods and services, INTA also released an NFT-specific white paper this week, in which it asserts, among other things, that “NFTs and other intangible assets no longer fit neatly into existing legal doctrines, especially in the case of fair use, artistic freedom, and the first sale doctrine,” and calls for the devlopment of “new legal frameworks to be developed to keep up with these fast-developing platforms and newly emerging digital ecosystems.”