On the heels of its short-lived legal battle against MSCHF over the company’s heavily-publicized Jesus and Satan sneakers, Nike is taking on the increasingly problematic custom market by way of a newly-filed lawsuit, with the Beaverton, Oregon-based sportswear behemoth asserting that it – and its wildly valuable trademarks – are facing “a growing threat [of] unlawful infringement and dilution by others that seek to unfairly trade-off of Nike’s successes by leveraging the value of Nike’s brand to traffic in fake products.” One of those third-parties that is looking to piggyback on the appeal of Nike and the burgeoning customization market? Drip Creationz.

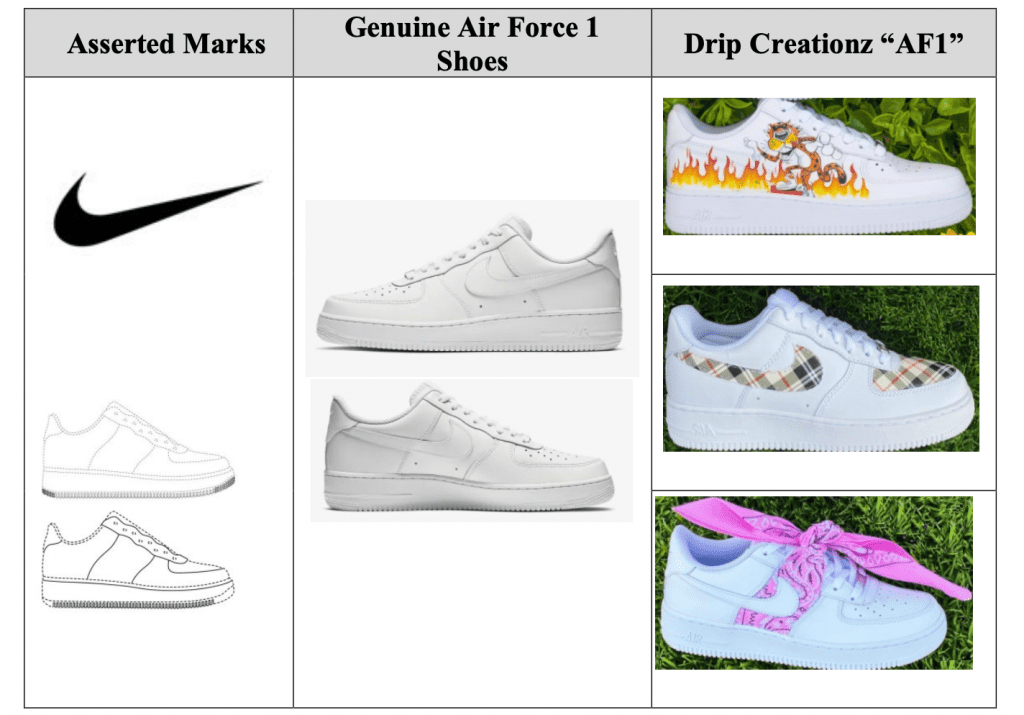

In the complaint that it filed in a federal court in California on Monday, Nike claims that Customs By Ilene, Inc., dba Drip Creationz (“Drip Creationz”), is on the hook for trademark infringement and dilution, and counterfeiting, among other causes of action, for offering up and selling products “purporting to be genuine Nike products, but that are, in fact, counterfeits,” namely, “knockoff Air Force 1-style shoes that it refers to as ‘D1’ shoes,” which bear designs that allegedly infringe upon Nike’s registered trademarks for to its Air Force 1 shoes and that have “crooked proportions, messy stitching, cheap details, and [are] taller than the real Air Force 1 shoes.”

Corona, California-based Drip Creationz does not stop there, though, per Nike. In what is the most interesting aspect of the case, Nike claims that in addition to offering up the unabashedly counterfeit Air Force 1 sneakers, which it advertises as “100% authentic,” Drip Creationz is also promoting and selling unauthorized footwear that it markets by way of its e-commerce site and to its 1.1 million Instagram followers as handmade “customizations” of Nike’s most iconic products.

The problem, according to Nike, is that in creating the customized footwear, Drip Creationz “deconstruct[s] Air Force 1 shoes” and “replace[s] and/or add material” to those otherwise authentic shoes. In the process, the defendant “materially alter[s]” the shoes “in ways Nike has never approved or authorized.” Specifically, the Swoosh argues that the custom shoes contain “images, materials, stitching, and/or colorways that are not and have never been approved, authorized, or offered by Nike,” including “fake and unauthorized Nike Swoosh designs, as well as third party trademarks and protected images,” such as a pattern that mirrors Burberry’s trademark-protected check, Frito-Lay-owned Cheetos’ Chester Cheetah character, Travis Scott’s Astroworld graphic, and Chick-fil-A’s stylized word mark, along with an image from one of the fast food chain’s its “EAT MORE CHIKIN” campaigns.

The unauthorized shoes are being promoted as “AF1” styles, and have “sold for over 140 percent of the retail price of genuine Air Force 1 shoes,” Nike claims, asserting that Drip Creationz is “likely to cause confusion, mistake, and/or create an erroneous association as to the source, origin, affiliation, and/or sponsorship of the [unauthorized footwear] products.” More than that, Nike asserts that such customization activities interfere with its exclusive ability “to choose who it collaborates with, which colorways it releases, and what message its designs convey,” considerations that it asserts “are an integral part of Nike’s branding and quality control over its designs.”

By offering up the unauthorized custom sneakers, Nike claims that Drip Creationz – which is “not an authorized distributor or retailer of Nike products” – is going “out of its way to deceive customers into falsely believing that they are purchasing genuine Nike products and/or that Nike has authenticated or approved of Drip Creationz’s products, in order to trade off of Nike’s brand and goodwill.” And according to Nike, it is “not surprising” that the defendant’s “tactics have led to numerous instances of actual consumer confusion,” as purportedly evidenced by comments on the Drop Creationz website.

Aside from confusing consumers, Nike claims that the defendant is diluting “the distinctiveness of Nike’s trademarks,” thereby, “weakening their unique ability to identify Nike as the source of its iconic Air Force 1 footwear designs,” which have “become famous in the United States and the around the world … as a result of Nike’s extensive sales, advertising, and promotion.” In turn, Nike claims that it stands to “lose control over its brand, business reputation, and associated goodwill, which it has spent decades building.”

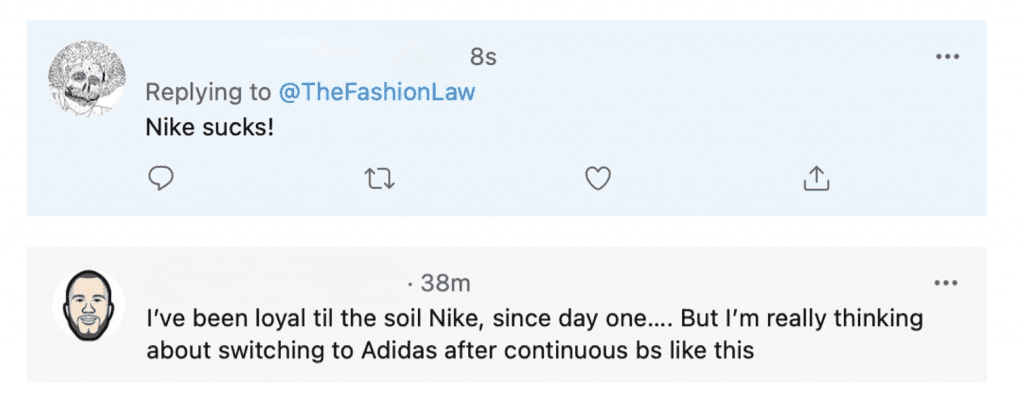

In a nod to the pushback that it will inevitably receive from consumers on social media (see one example below) and beyond for filing suit and in what appears to be the latest acknowledgment of the fact that brands’ counsels are increasingly being forced to consider and attempt to mitigate the public relations elements that come with initiating legal battles, and balance those concerns with the need to police unauthorized uses of their marks, Nike claims that “it has no desire to limit the individual expression of creatives and artisans, many of whom are some of Nike’s biggest fans.” At the same time, though, it says that it “cannot allow ‘customizers’ like Drip Creationz to build a business on the backs of its most iconic trademarks, undermining the value of those marks and the message they convey to consumers.”

“The more unauthorized ‘customizations’ get manufactured and sold, the harder it becomes for consumers to identify authorized collaborations and authentic products; eventually no one will know which products Nike has approved and which it has not,” Nike claims, noting that such customizations are not a harmless endeavor, and the damage its experiences as a result is “considerable.” Against that background, Nike says that it has filed this suit “to stop ‘customizers,’ like Drip Creationz and others, from making and selling illegal ‘customizations’ of Nike’s products and other products illegally using its trademarks, and to protect its brand, goodwill, and hard-earned reputation.”

With the foregoing in mind, Nike sets out claims of trademark counterfeiting and infringement, trademark dilution, false designation of origin, and unfair competition in connection with Drip Creationz’s unauthorized use of an array of its trademarks, including its Swoosh logo, which it says is “one of the most famous, recognizable, and valuable trademarks in the world,” as well as its Air Force 1 word mark and trade dress. The sportswear titan is seeking monetary damages in an amount to be determined at trial, and injunctive relief to bar Drip Creationz from further infringing its marks and/or injuring its business reputation, among other things.

The case is the latest example in a growing string of matters that center on the third-party modification of products and the subsequent offering of those goods in a commercial capacity, with such cases pitting brands’ ability to control unauthorized uses of their famous trademarks against arguments that center on fair use and the First Sale doctrine, the latter of which generally enables someone who has purchased a trademark-bearing product to resell that same product without facing infringement liability, subject to certain conditions. Chanel is currently in the midst of a legal battle after initiating a trademark infringement and dilution case over the sale of jewelry crafted from allegedly authentic Chanel branded buttons, while Rolex, Ralph Lauren, Swatch subsidiary Hamilton International, and a number of other brands have faced similar issues in the recent past.

The case is Nike, Inc. v. Customs By Ilene, Inc., 5:21-cv-01201 (C.D.Cal.)