In 2014, Amazon enabled China-based entities to sell directly to its members in the West, and in the process, grew its sales by a whopping 20 percent in a single year, prompting its total revenues to blaze past the $100 billion mark for the first time. The move foreshadowed the close of its China-specific site, which was born from its takeover of Joyo.com, that would come several years later. In an attempt to grow its pool of third-party sellers and thus, its revenue, Amazon corralled Chinese sellers onto its main site opening what the New York Times’ John Herrman calls “cross-border e-commerce parks, where sellers can get assistance with logistics, branding, and navigating Amazon’s platform.”

At least some of these sellers – whose brands names, such as Pvendor, RIVMOUNT, FRETREE, MAJCF, Nertpow, SHSTFD, Joyoldelf, VBIGER and Bizzliz, adorn “thousands of new product lines” and “disparate categories of goods, many evaporating as quickly as they appeared” – are bringing in $1 million per month selling everything from “nail clippers, scissors and electric razors” to basic garments and accessories thanks to their dirt-cheap prices paired with the lure of free, fast shipping for Amazon Prime members, and in many cases, “driven by high search placement and customer reviews.”

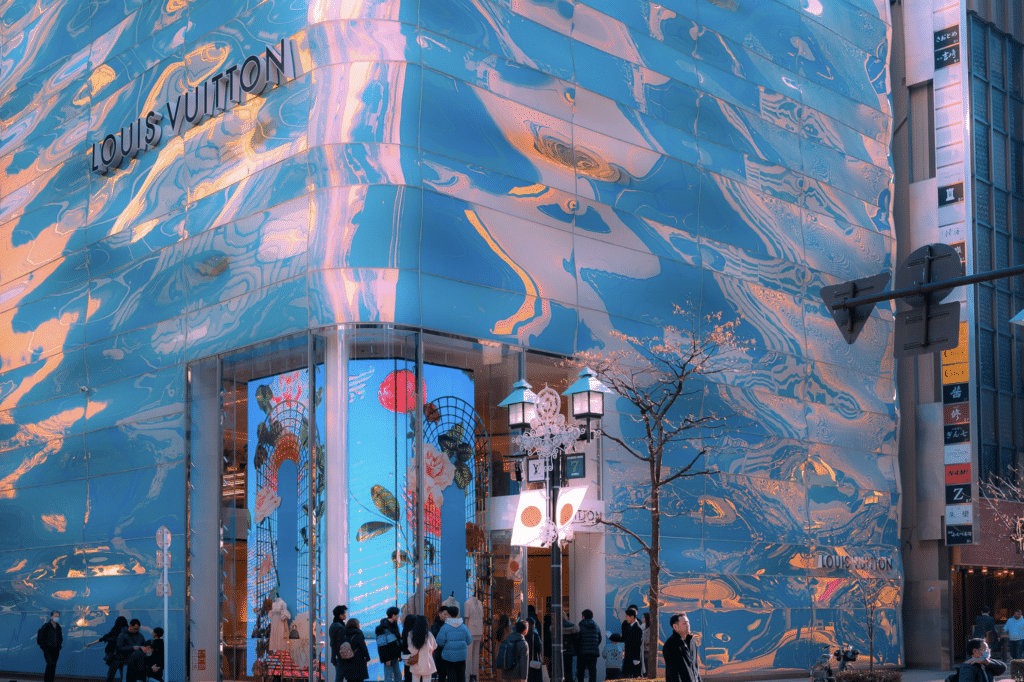

At the same time, these brands are actively “challenging what it means to be a brand,” Herrman states in a lengthy piece about the evolution of Amazon and its third-party marketplace, noting that the branding of these “commodity goods, or types of products where shoppers don’t have much brand loyalty in the first place” is not necessarily important, certainly not in the way a cult skincare brand’s name is or the way a goodwill-soaked luxury logo is.

“A product can succeed without a brand, or even despite one,” he writes, while intellectual property lawyer CJ Rosenbaum concurs, claiming that “the name of the brand has become less and less important.” Instead, the marketing of products within the Amazon ecosystem (and beyond) “is probably more important,” per trademark lawyer Timothy Wang. In other words, consumers likely do not care all that much about what brand name (read: trademark) comes on a cheap pair of gloves or a basic white t-shirt. They are buying the product, largely because of its price-tag; they are not really buying into the brand and the goodwill associated with it.

However, where trademarks – i.e., words, names, symbols, logos, or designs, etc. used to identify and distinguish the goods of one brand from those of another – become particularly relevant is in connection with Amazon’s Brand Registry. In 2015, Amazon – facing seemingly endless, sometimes-very-public complaints about the authenticity of the offerings on its sweeping third-party marketplace and its efforts (or maybe, the lack thereof) to grapple with that reality – rolled out a new initiative. Called Brand Registry, the Amazon effort aims to enable companies to “protect [their] brand” and to protect customers, as well, by “helping to provide accurate representation of trademarked brands” on its site, according to the $1 trillion Seattle-based e-commerce titan.

In addition to giving brands tools to more easily ward off counterfeits, the Brand Registry enables brands to “gain better control over their product listings,” per Amazon. “Crucially,” Herrman asserts that participation in Amazon’s Brand Registry also gives sellers “more access to advertising solutions, which can help you increase your brand presence on Amazon,” as well as to “utilize the Early Reviewer Program to gain initial reviews on new products.” In other words, “To achieve real and lasting success on Amazon, [participation in the Brand Registry] vital.”

The catch for many of these Chinese pseudo-brands”? In order to be eligible for the Registry, a company must have a registered trademark in the U.S. And so, no shortage of these Amazon sellers are making a beeline for the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and seeking to register new trademarks in order to be eligible for Amazon’s Registry.

The result comes in the form large swathes of trademark registrations, which could help to explain the spike in trademark applications being lodged with the USPTO from Chinese filers, and also the “surge of fraudulent applications originating from China” that has exacerbated the existing “problem of trademark depletion,” as New York University Law professor Barton Beebe told the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Intellectual Property in December.

Beebe’s testimony made specific mention of the fact that “a substantial proportion of applications originating in China include fraudulent specimens of use.” In other words, in an attempt to get around the USPTO requirement that an applicant must provide proof that a trademark is actually in use before a registration is granted, many filers are submitting photoshopped specimens, thereby, committing fraud in order to bag a registrations.

Speaking to the influx of trademark registrations for brands like Pvendor, RIVMOUNT, FRETREE, MAJCF, Nertpow, SHSTFD, Joyoldelf, VBIGER and Bizzliz, Wang told the Times that “a lot of foreign vendors aren’t too sophisticated in designing a trademark,” noting that “a lot of people just come up with random letters.”

The significance of this growing penchant for random – and often meaningless – names goes beyond a lack of branding sophistication, though. As Wang states, “If just have a bunch of random letters, people can’t say this is too similar to their marks.” Such a similarity could stand in the way of a trademark application turning into a registration, as the USPTO will not register newly-filed marks that are confusingly similar to already-registered ones.

“There are only so many English words,” Wang says, and frankly, most of those words are already registered with the USPTO. And with that in mind, this trend towards seemingly nonsensical brand names speaks to the “severely depleted supply of available trademarks [in the U.S.], particularly in certain sectors of the economy,” per Beebe and fellow NYU Law professor Jeanne Fromer. In what is likely a response to the ever-shrinking number of words that remain unclaimed by companies in any given sector (i.e., depletion), new brands are being forced to “to resort to second-best, less competitive marks,” Beebe and Fromer assert. Hence: the likes of VBIGER and MAJCF.

(This phenomenon is not limited to Amazon sellers. As we noted this fall, a sizable number of new (and new-ish) brands – such as Kassl, CQY (pronounced coy), SVNR (pronounced souvenir), SLVRLAKE, YSTRDYS TMRRW, GFT, LPA, KKCo, and KKW, the latter of which is Kim Kardashian’s beauty venture – are dropping letters from existing words or simply adopting monikers that consist of just a few letters in order to adopt distinctive names).

As such, many companies have seemingly found a way to beat the system so to speak in terms of gaining trademark registrations. But the situation on Amazon is not without potential complications for those trademark holders. As Herrman states, in many cases, sellers “use Amazon’s brand name [and the reputation associated with it] to sell their products,” and even when the seller at play actually does have a brand name, such as UGBDER, the brand is still “more Amazon than UGBDER. That is because it is “sold under the Amazon banner, through Amazon Prime, fulfilled by Amazon and shipped in an Amazon box, perhaps even purchased through an Amazon device.”

That raises an interesting question for trademark experts. As Harvard Law School intellectual property and advertising law professor Rebecca Tushnet posited on Twitter, “Is this failure to function?”

While the operator of the UGBDER brand very well may have a registration for the word for use on specific classes or goods/services, that registration may be one that could successfully challenged and invalidated on a failure to function basis, or in other words, an inability of the mark to actually indicate a single source or distinguish goods or services because of the way in which it is used. In the cases at hand, these little-known third-party sellers marks are used under the umbrella of all things Amazon, including maybe most significantly, Amazon processing and packaging, something that very well may nullify any potential brand name recognition of a company like UGBDER, a company that consumers are relying on for the products and not for the brand, itself.

This is something that may be lost on trademark examiners, who are not necessarily tasked with looking at the trademark’s actual operation in the market (i.e., whether it is sold on Amazon’s marketplace or on its own website with the UGBDER.com domain name, for example), and instead, are more commonly looking at whether the mark at issue is different enough from those already registered and whether the filing party can prove actual use.

That is, of course, just one of the questions that Amazon’s “peculiar relationship with trademarks” – as Herrman puts it – paired with the ever-rising number of trademark filing and the increasingly crowded trademark landscape raises.