On the 17th of every month, Burberry wants consumers to get in line. In order to build hype and thereby, boost its revenues, the British heritage brand, under the control of creative director Riccardo Tisci and CEO Marco Gobbetti, is courting younger customers, ideally the same ones that have driven Gucci out of its pre-Alessandro Michele doldrums and made it one of the industry’s fastest-growing and most revenue-happy brands.

With this in mind, Burberry – which is in the midst of a new, and ideally, more profitable, era with the help of former Celine CEO Gobbetti and Tisci, who is famed for turning Givenchy into a modern luxury haven with street cred – will make new designs from its ever-growing B Series collection available for purchase on the 17th of each month by way of its Instagram and WeChat accounts for just 24 hours (starting at 12 pm U.K. time) – or if all goes well, until the goods sell out.

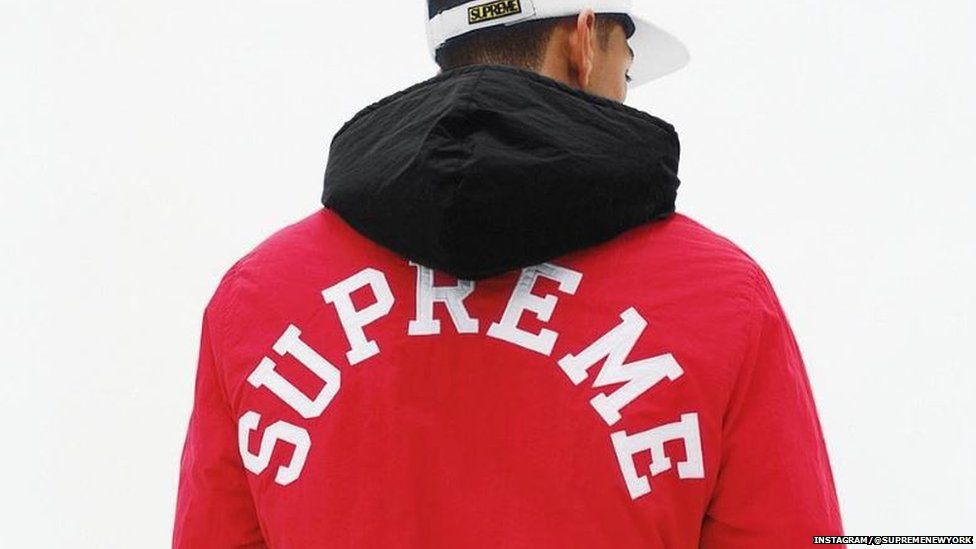

According to British Vogue, each launch will range in scale and availability, “but one thing will stay consistent: Tisci wants to remain in constant communication with his customers,” and he will do so by taking a page from cult streetwear/skatewear brand Supreme’s book and implementing the drop model.

Burberry is the latest in a line of brands aiming to adopt the model that has been successfully in place at Supreme for more than two decades, one that sees the brand “drop” new pieces weekly, almost always on Thursdays at 11am.

As London-based leadership advisory firm MBS Group’s Moira Benigson stated last year, “The concept is fairly simple; unlike the traditional fashion houses, whose seasonal collections are released in one go-around [several] times per year, smaller fashion companies like Supreme tease out the sale of their collections, dropping a few items each week.”

Another imperative part of Supreme’s distribution equation: courting demand by limiting supply, or as writer Justin Gage put it recently, Supreme – and other similarly situated streetwear brands – “operates on wartime supply and demand curves.” In other words, the likes of Supreme ignore the traditional model and instead, they “fix supply and ignore demand. As a result of the quick sales of all of the “dropped” stock and the crowded (and highly liquid) resale market for such stock (where prices demanded are significantly greater than at initial sale), these brands can manufacture scarcity to drive hype.

One of the most obvious results of this practice of product distribution? The long lines that stretch around the block of a Supreme brick-and-mortar outpost, and the 16,800 percent spike in traffic to Supreme’s website that has been known to occur each month. But beyond Supreme’s ability to lure in streetwear fanatics and resellers (who buy up Supreme goods and flip them for eye-popping prices on any of the growing number of resale platforms), its drop model also has caught the attention of both fashion – and non-fashion – brands that are looking to inject some relevance into their traditional distribution mechanisms.

According to Benigson, “Small-batch craft beer, [and] one-off collaborations on new designs can all use the drop model to their benefit.” And that is precisely what a whole slew of consumer goods brands doing: releasing limited runs of new products in order to build hype and sell more of their core offerings, whether those products be runway handbags, buzzy millennial-driven cosmetics, or burgers

As Digiday noted recently, “Companies spanning a range of categories, from fast food giant Shake Shack [which is using the drop model to drive installations of its mobile app to test out new items before bringing into full force] to toothbrush subscription service Quip, are adopting the drop model to launch new items of their own on social [media] that they expect to sell out quickly.”

Much like Burberry and the streetwear brands before it, these companies are placing their bets on the “limited-release, [which] is now a cultural phenomenon that can be co-opted for a marketing jolt in the form of social media chatter.” And it is working. “We’re getting to a regular cadence,” Elliot Friar, brand manager at Quip, told Digiday. “It’s [feels] natural for us to drop something because we want user feedback and immediately gauge our users.”