In the spring of 2017, the French government published a new law directly aimed at the fashion industry. Following years of back and forth between legislators and industry entities in France, and on the heels of governments and/or trade organizations in India, Israel, Italy and Spain introducing measures to address health and wellness in the fashion industry and beyond, French legislators revealed that they would require models to possess a medical certificate confirming that they are in good physical health (i.e., they are not “too skinny”) in order to legally work in France.

Specifically, the law – which was formally published in May 2017, after first being introduced two years prior with a number of amendments implemented in the interim – aims to “avoid the promotion of beauty ideals that are inaccessible and to prevent anorexia in young people,” according to France’s Minister of Social Affairs and Health Marisol Touraine. In furtherance of that goal, the legislation requires that models undergo a medical examination every two years in order to get their hands on a medical certificate attesting to their good health.

According to the law, doctors may take a model’s body mass index (“BMI”) – which is calculated by dividing their weight by the square of their height – and the World Health Organization’s consideration that a person is underweight if their BMI is below 18.5 into account when making such a health assessment, something that has been met with notable backlash from industry entities due to the potential inaccuracy of the metric in gauging an individual’s overall health.

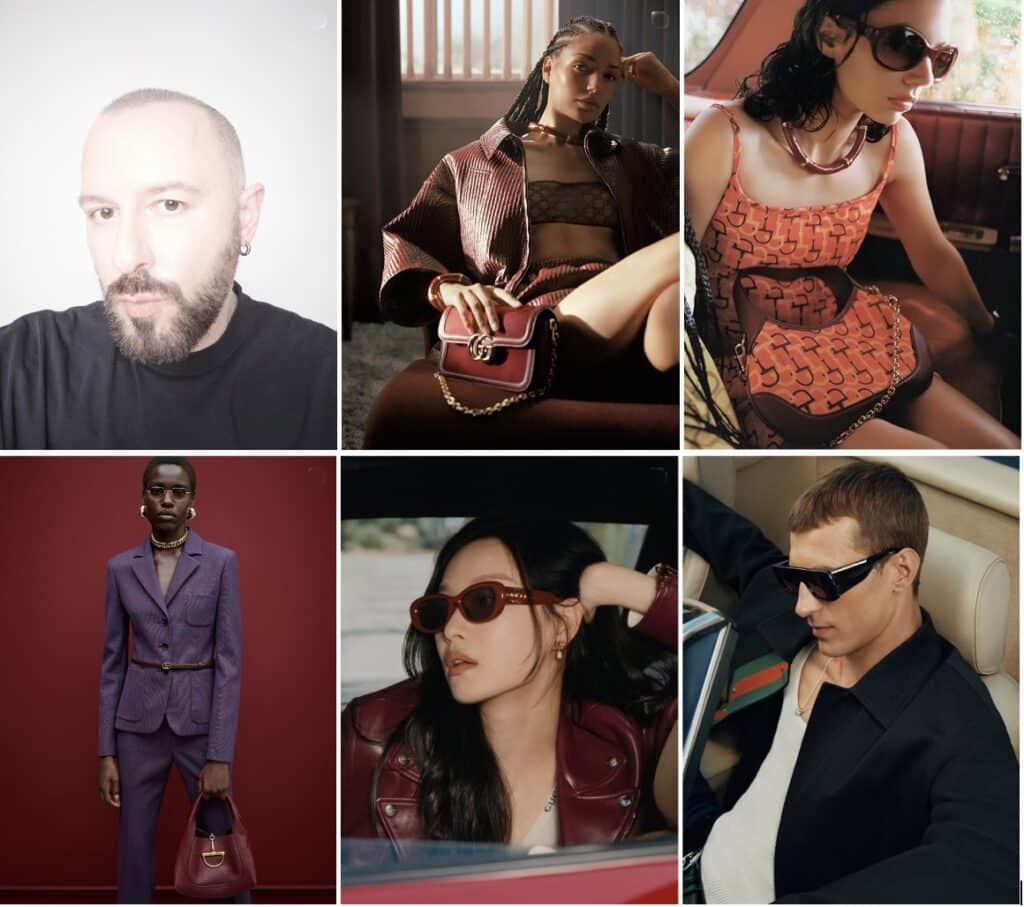

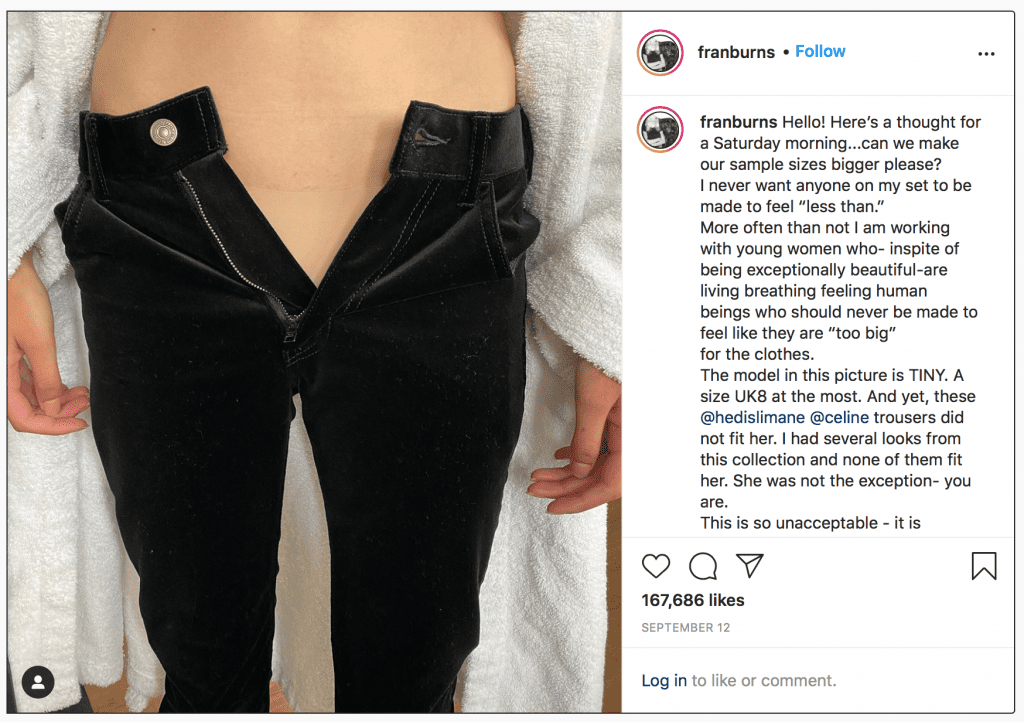

Now, more than three years after the “model law” first went into effect, recent discussions within the fashion industry raise questions about what – if anything – has changed since then. In September, for instance, stylist Francesca Burns sparked an industry-wide discussion when she posted an image of a model that could not zip the sample-size Celine trousers she was wearing.

In the since-gone-viral Instagram post, Burns stated that the Hedi Slimane-designed trousers did not fit the model, despite the model being “TINY … a size UK8 at the most.” Burns said that while “had several looks from this collection, none of them fit” the model. The unnamed model “was not the exception – you are,” Burns asserted, addressing Celine and Slimane, the brand’s highly-respected creative head. “This is so unacceptable – it is fundamentally wrong to suggest that this is the norm. It isn’t.”

In an interview with Vogue days later, Burns said that this was hardly a one-off scenario: “On probably nine out of 10 shoots I style there will be sample clothing [lent by fashion brands] that doesn’t fit the talent, especially if you’re working with actors or non-professional models. In many instances, the sample sizes are so small that they don’t even fit the professional models.” Moreover, she asserted, “In many instances, the sample sizes” – i.e., the ones commonly worn by models in brands’ runway shows – “are so small that they don’t even fit [many] professional models.” She noted that “in order to fit into ‘the sample,’ many professional models have to adhere to the same very slender body type” that dictates the runway “sizing that is used by many major fashion houses.”

Burns’ Instagram post was met with widespread encouragement from models and other industry insiders, alike. Some pointed to the fact that the French model law is “staggeringly easy to work around.” Others questioned the level of precision that a health certificate that is valid for a period of two years actually entails. Ultimately, LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton-owned Celine’s sizing, taken at face-value, is difficult to reconcile with the legally-binding mandate that France has in place to ensure that working models are not unhealthily-thin, and raises broader questions about how much of an impact the law has had over the past three years.

While the French regulation gave the country’s Ministry of Social Affairs and Health the opportunity to “lay down clear, penal sanctions in the event of failure to comply with the obligation to provide a medical certificate,” according to Paris-based attorney Céline Bondard, it does not guarantee that such a law will, in fact, be enforced. And, in fact, Bondard says that she has not encountered any cases involving the law since it was enacted.

Looking beyond the French law, enforcement of these model-centric laws has been relatively lax if Israel is any indication. In a June 2017 report, which was published more than four years after the Israeli government passed its own “modeling law” in order to address “the creation of low body image and the development of eating disorders in Israel,” the Knesset Research and Information Center found that little enforcement had taken place.

For instance, the Center’s Renana Gutreich revealed in the report that Israel’s Ministry of Economy and Industry informed the Knesset Center that “no one in the Ministry was appointed to be in charge of the enforcement of the law,” and in fact, there was an active “dispute among the Ministries as to which of them ought to be responsible for the implementation of this law.” More than that, Gutreich stated that when asked for information about “the number of medical certificates regarding levels of BMI issued to models since the law came into force,” the Israeli Medical Association, four individual healthcare firms, and Tel Aviv-based modeling agency Yuli Group did not have “any information” on the subject.

At the same time, in Spain, where a similar ban was enacted in 2006 – albeit on a private, non-governmental level by the Spanish Association of Fashion Designers trade association – to keep models with a BMI of less than 18 off of the runway, the results have been mixed. According to local media reports, “Nearly a third of models were banned from taking to the catwalk in the first year the rule was introduced.” Since then, however, the effectiveness of the ban has been questioned. Speaking anonymously shortly after the ban came into effect, a model told the Observer that when she walked in runway shows during Madrid Fashion Week, agencies were actively engaging in “loopholes,” giving underweight models “Spanx underwear to stuff with weights” when it was time to step on a scale.

In terms of the effectiveness of such legislation going forward, there is a delicate balance in play. Due to the potential imprecision of the factors used to gauge models’ health, including the BMI metric, Bondard, for one, says that there is a “risk of discrimination against models deemed too thin when they are, in fact, fit to work.” While she notes that the fashion industry has a duty to protect the health of models, themselves, and of individuals more broadly by “fighting against stereotypes related to thinness and preventing behaviors that are harmful to health, especially among young people,” it is also important that such legislation – some of which comes with the potential for imprisonment and/or monetary penalties – not “unnecessarily stigmatize ‘naturally’ thin people.”

The French law has not necessarily mastered this balance, but Bondard says that it is “a useful French regulatory development in principle,” particularly given that it has been supplemented by voluntary charters adopted by certain private groups, namely, the September 2017 charter put forth by LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton and Kering, which “go beyond the applicable legislation to frame concrete situations and unify practices.”

That assumes, of course, that the two industry giants are, in fact, enforcing their own voluntary pact.

As for Burns, she says that things should be different, particularly since “modeling is work and a fashion shoot is a workplace.” She has implored fashion businesses – large and small – to address such “sizing issues,” in light of the fact that the industry and its occupants “have a huge part to play in the representation we see on the page and screen.”