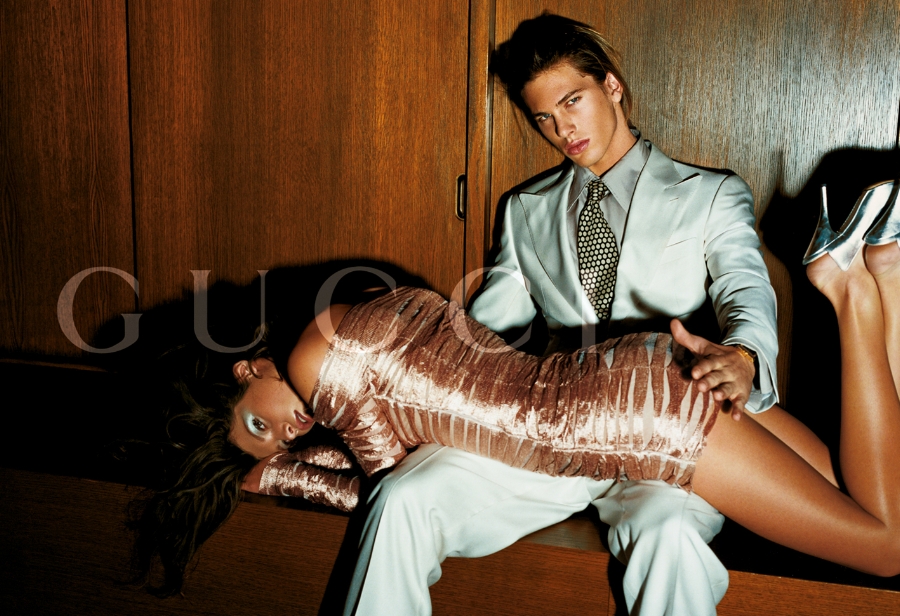

image: Gucci

In addition to victimizing women – by way of ad campaigns and editorials, alike – fashion thrives on the practice of objectifying women. This is a long-standing practice and in recent years often includes hyper-sexualized fragrance ads for the market’s biggest brands, and extends to apparel and cosmetics ads – for Tom Ford’s eponymous label, for instance, and during his tenure at Gucci from 1990 to 2004. As Fern Mallis said in 2015, Ford “understands more than anyone else that sex sells.”

While sex does sell – or at least, sells when it is in style, which is frequent – is its hyper-specific depiction, one that almost exclusively serves to objectify women, good for the fashion industry? And better yet, is it good for women in general or does it drive home our larger social sense of sexism and a potential lack of value for women? These are particularly relevant questions in light of the larger conversation about sexual harassment and assault in Hollywood, in fashion, and beyond.

This is also a relevant inquiry, as it is the product du jour being peddled by fashion photographer Terry Richardson (and others), who recently came under fire – for the nth time – for allegedly sexually harassing and assaulting models, many of whom were young, vulnerable, and on the job at the time.

Most of Richardson’s photos – whether they be for his own site or for major brands’ ad campaigns – are sexually charged, others are downright depreciating and exploitative. But Richardson – who has been linked to many a highly questionable ad campaign, including those Sisley ones in the mid-2000’s and a slew of questionabe ones for Tom Ford – is merely part of a much larger issue. Or as the New York Times put it, he is just the “tip of the iceberg.”

Yes, as the Washington Post’s Robin Givhan wrote last week, the problem is much larger than Mr. Richardson. It involves all of the “creative types who treat women as something other than sentient, thoughtful, individuals,” those that “still manage to treat women like crap.”

image: American Apparel

There are countless examples within the past 15 years, alone, of fashion demeaning women in the name of commerce. Consider nearly every Dov Charney-era ad for American Apparel. How about the many Tom Ford campaigns for his eponymous label, in which fragrances are positioned between models’ breasts or between their legs? Do not forget that Dolce & Gabbana very notoriously released what has been coined its “gang rape ad,” which feminist writer Louise Pennington called “a representative of an increasingly misogynistic contraction of women in the fashion industry.”

As recently as last year (six years after releasing a campaign featuring a semi-naked Lara Stone on the ground being manhandled by a gang of male models), Calvin Klein put forth a campaign in which female photographer Harley Weir photographed a model from under her dress.

Speaking of Calvin Klein, just yesterday, Milk Studios posted what appeared to be a retro image of a model’s behind, barely covered by a pair of Calvin Klein underwear, prompting veteran fashion journalist Christina Binkley to respond, “This ad is part of the problem. Some art director loved it, but what’s the [message] and who is it for?”

While Binkley – an inherently thoughtful individual – might question the motive behind the image, it has gotten to the point that, as writer Lauren Wade, put it back in 2014, “as a whole we’ve largely gotten used to seeing women depicted this way.”

image: @MilkStudios

Not only is it perfectly commonplace to see women sexualized and represented as objects used to sell products (and note: women are depicted in this way with significantly more frequency than male models are), such imagery is being put forth for the sake of “fashion.” And it is here that we really encounter problems.

With this in mind, the question becomes, can we expect fashion to change its tune in terms of its practice of using women to sell sex and more specifically, fragrances or ready-to-wear? Also, can we expect the industry to be explicit with its values and thereby, begin placing greater worth in women, which includes how they are depicted in the media and in ad campaigns?

The answer: Probably not, in part because the fashion industry is, oftentimes, reacting to the desires of the zeitgeist at large in creating marketing materials, which it will happily remind you. Change here would, thus, mean altering the cultural underpinnings of consumer preferences and purchasing decisions. And that is no small feat.

However, having said that, fashion – as a key creator and disseminator of culture – has very substantial power in terms of affecting the larger social narrative. This is a fact.

We – as the media, as consumers, as active participants in the conversation on social media and elsewhere – need to stop praising ads that objectify and/or belittle women as “provocative,” as “art,” and as “fashion.” Because this is not “art” and it is not “fashion.” It is objectification and it is damaging.

The good news? With an increasing number of women taking roles that were – for many years – dominated almost exclusively by men, including CEO and creative director positions at major houses, it would be easier than ever before for them to flip the switch, so to speak, on advertising that objectifies women. Such messaging simply does not need to be “in style” and frankly, it should not be any longer.