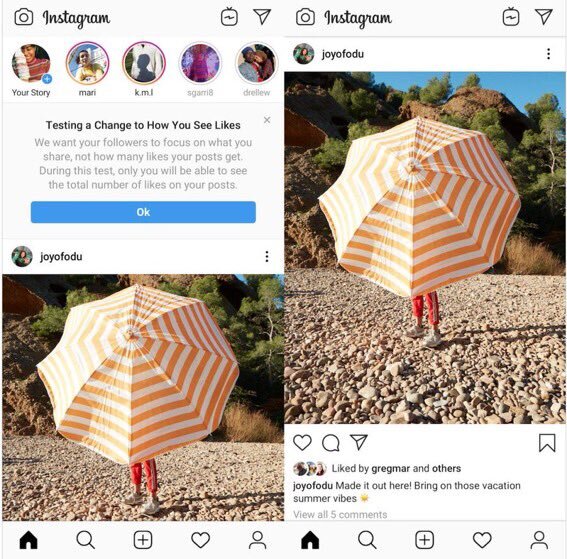

On the heels of Instagram’s decision to remove its visible “like” counter from its platform in certain geographic regions, such as Canada and Australia, earlier this year, the app’s operators say they will perform the same test in the U.S. beginning this month. The roll-out by the Facebook-owned photo and video-sharing app is being touted as larger ethos, which will see Instagram “make decisions that hurt the business if they help people’s well-being and health,” according to Instagram’s CEO Adam Mosseri.

There are certainly advantages to such an action, most of which center around the potential effect that the hiding of “likes” will have on users’ self-esteem, since removing “likes” is being likened to a removal of the incentive to treat social media as a form of numbers-based competition. In other words, the removal of users’ “like” scores may function “to restore the more socially collaborative” – rather than competitive slash comparative – “nature of social media, and may improve user self-esteem in such a way that social validation may have to come through substantive engagement as opposed simply comparing ‘like’ counts,” says Western University Information and Media Studies professor Kane Faucher.

On the other hand, questions abound as to how the removal of “likes” will impact social media influencers, many of whom depend on the visibility of the size of their audience and level of engagement – as demonstrated, at least in part, by likes. To be exact, many are questioning how will this new initiative – which will still enable users to see their own metrics but will hide them from other users – might affect the ease with which influencers can enter into advertising partnerships and the rates that they can demand from brands for posting endorsements, something that no long depends (in many cases) exclusively on the size of their individual audiences but on engagement levels, as well.

Without visible “like” counters in place, Faucher says that “it makes it much harder for influencers to make the case that they are, indeed, influential in the endorsement of products and services, and it potentially reduces their ability to pitch their effectiveness to companies in securing new work.” More than that, he says that the removal of visible “like” counts “may make it even harder for new social media influencers to build their reputations, while enabling already-established influencers to prosper on the basis of their existing follower base” and past track records.

Aside from impacting influencers, brands are expected to be affected, as well, particularly since they also rely heavily on the metrics produced by counters of comments and “likes” to measure the reach of the influencers they are working with – or might want to work with – and to test marketing tactics of their own aside from influencer-specific marketing campaigns.

image via Instagram

image via Instagram

Ultimately, Faucher suspects that without having easily-viewable numbers to assess performance and justify expenditure, the removal of the “like” counter may deprive businesses of some much-needed market intelligence. (Although, this is almost certainly somewhere that Instagram can and probably will step in with a service … for a price).

At the same time, there are other measures that can be utilized by brands and influencers. As Ali Grant, the founder of digital communications agency Be Social, stated last month, “There [will] still [be] access to the number of swipe-ups on Instagram Stories, click-throughs from the link in your bio, new followers to a page, and the number of comments,” meaning that “likes” are hardly the the only measurable KPI – or key performance indicator, even if they are more telling than some other figures. Faucher notes, for instance, that Instagram sans counters does “not provide as easy a path to track return on investment” as it does when “likes” are in play. “There may be a follower count,” he states as an example, “but that speaks only to impressions not engagement.”

Finally, there is one more entity that stands to be affected by the removal of visible “likes” that cannot be overlooked: Instagram, itself, since much of its revenue stream is derived from advertising and in particular, its ability to match ads to users based on their activity on the app. In order to do so, Instagram “looks at a user’s time spent logged in and his/her engagement (viewing, posts, likes, etc.),” per Faucher, meaning that “some form of metric must remain in place – publicly visible or not – in order for the company to make the case that there is a good return on investment for ad placement.” This, after all, will be essential to Instagram, which generated ad revenue of a whopping $9 billion in 2018. That figure is emptied to grow to as much as $14 billion for 2019, according to fresh estimates from Jefferies, making the identification and measuring of a user’s “activity, including “likes,” a staple element in the operation of the app.

Instagram will likely make metrics easily accessible for influencers and businesses in connection with their own accounts in a behind-the-scenes capacity, and it would not be surprising if it provides such a service in exchange for a fee. After all, it would not be the first time that it looked to boost its in-app non-advertising revenues.

For instance, the company announced in April that it would introduce a new feature – which lets influential individuals “tag products in their posts, giving [their followers] the ability to buy whatever they may be wearing (from apparel to cosmetics) directly from the app.” More than merely extending its tagging/shopping capabilities to individuals for the first time, the move paved the way for Instagram to take a percentage of all sales that occur on its platform, while cutting out middlemen, such as influencer monetization platforms like rewardStyle’s LIKEtoKNOW.it app, which have built businesses doing that very thing.

Even if it does provide intel to brands and influencers, Instagram may still be walking a fine line with influencers and brands, and this is critical, since, as Intelligencer stated this spring, “Social networks need influencers as much as, possibly more than, influencers need them.” Influencers “drive traffic that platforms can sell ads against, and it’s often creators, not the platforms, who show companies the full use and scope of what the product they have built can do, Intelligencer’s Madison Malone Kircher wrote in May, likening the potential problem to the one that Snapchat experienced.

“If you were a rising Snapchat star looking to do sponsored content or branded deals, you had to take it upon yourself to prove to those companies that you were worth the investment — it wasn’t immediately apparent who was popular and highly sought-after, unlike on Instagram.” The same could soon be said for Instagram.