Whether it be $4 shirts from H&M or $800 tees from Christian Dior, prices in fashion are extreme and becoming increasingly out of control. A phenomenon that occurs at both ends of the spectrum, with fast fashion and high fashion entities, alike, the proliferation of such pricing disparity appears to symbolize something significant: Consumers have lost touch with how much garments are supposed to reasonably and responsibly cost.

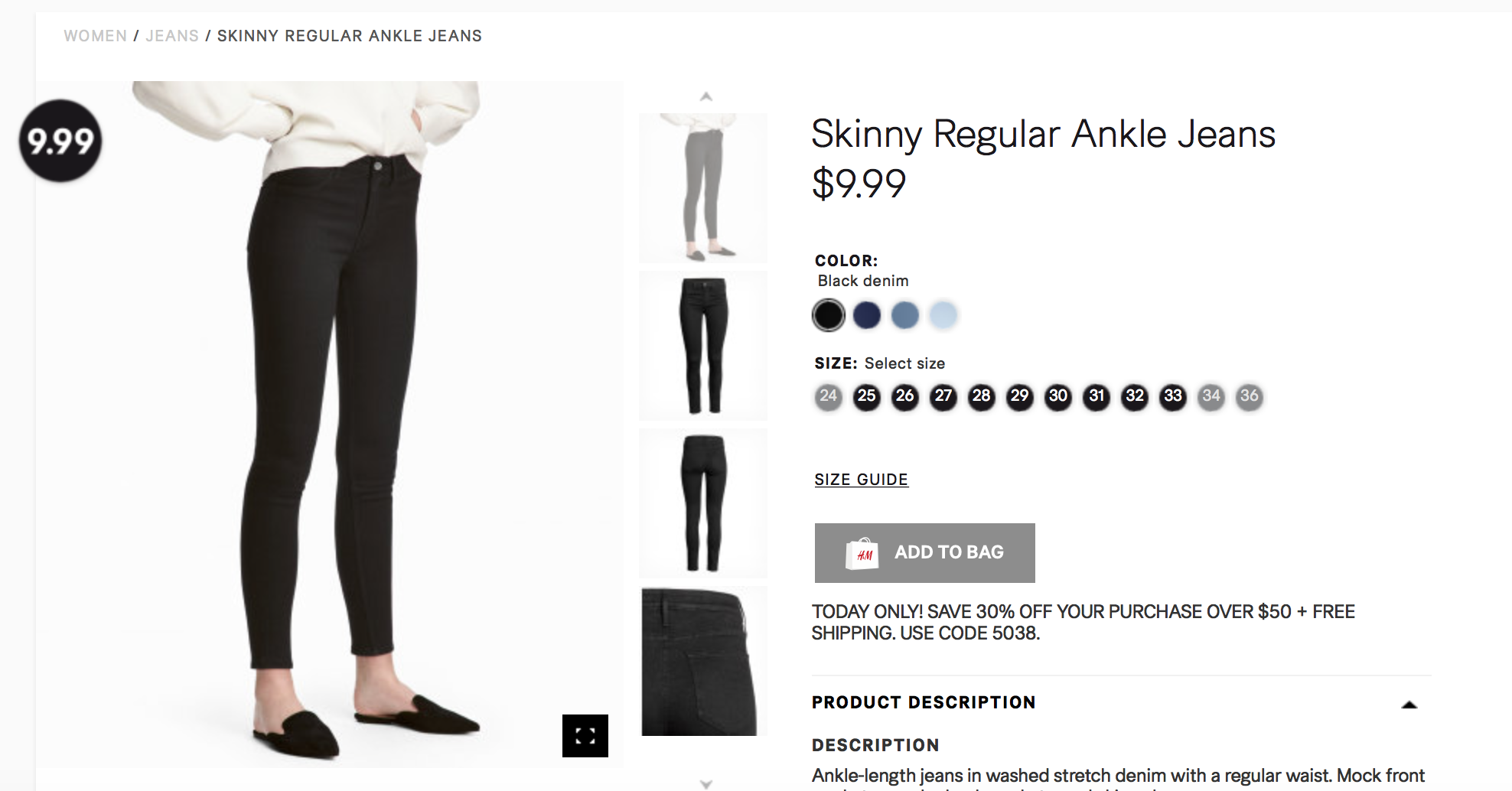

With dirt-cheap garments being put forth by the likes of Forever 21 and eye-poppingly expensive ones hitting the shelves at high fashion brands’ outposts, the question becomes: Why the $800 asking price for Dior’s “We Should All Be Feminists” tees? And conversely: Why is it normal for jeans to cost $9.99?

How Low Can You Go?

The reasons for such price extremism are many and part of a much larger web. Nonetheless, there are a few key contributors worth examining. On the low end, prices of garments and accessories have become increasingly affordable due to an array of technological and global factors. In light of the industrial revolution, for instance, which saw the large-scale transition from hand production methods to machines-made goods, garments and accessories have become significantly more affordable.

Prices lessened further when brands began outsourcing labor en masse to low-cost manufacturing centers. Originally, this was China, but as costs have steadily been rising there, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Thailand, and Egypt, etc., have become popular sourcing destinations; even Chinese factory owners have taken to outsourcing there.

Mexico – and the countries to which it outsources – has also become a sourcing hub in light of the North American Free Trade Agreement (“NAFTA”). Many of these manufacturing destinations boast costs that are unimaginably low thanks to the widespread economic exploitation of labor.

Still yet, most fast fashion brands take this a step further by maintaining supply chains that rely significantly on oft-undocumented contractors and subcontractors, dominated by low-cost labor and overarching lack of strict ethical standards (more about that here). They frequently change their suppliers of choice in search of those willing and able to manufacture at the extreme lowest costs. This makes it possible for brands to source garments and accessories for previously unimaginable costs.

One of the most striking aspects of the ever-falling prices at which clothing can be manufactured and sold – whether it be $4.99 for a top or $25 for a pair of jeans (the latter is a full $75 less than the loosely agreed-upon minimum of how much denim should reasonably cost in order to avoid ethically problematic and inhumane manufacturing processes) – is how widely advertised these prices are by some of the markets largest retailers and the impact that has on the larger consumer psyche.

Widespread marketing by way of campaigns boasting inexpensive H&M and Zara garments or Instagram ads touting dirt-cheap Forever 21 and Mango wares, for instance, has led to a collective belief amongst consumers that these prices are how much clothing should cost, and anything above these prices reflects an unnecessary markup.

That is, of course, a wildly skewed narrative that is part of a larger exercise in normalization. As eco-activist and founder of sustainability consultancy Eco-Age, Livia Firth, aptly noted not too long ago, “We have been brainwashed in the last fifteen, twenty years, to think that it’s democratic to buy a t-shirt for five dollars.”

She elaborated, saying, “Today, [mass market retailers] have flipped our perception so now we think [a t-shirt for five dollars is] a bargain we have to have it, it’s so cool and the kids – the 15-year-olds, the 20-year-olds – today think that it’s completely normal.”

And she is right, especially if we consider the size of many of these mass-market retailers and the power they have in dictating the reasonability of prices in the minds of consumers. Inditex (Zara’s parent company) and H&M, for instance, are the two largest apparel retailers in the world, making Zara and H&M two of the retailers with which consumers most frequently come in contact.

With that in mind, these brands have the power to control what consumers think is reasonable and/or responsible and what many other retailers think is competitive when it comes to the pricing of garments and accessories. The result: Bottom-of-the-barrel prices across an entire section of the market have become the norm rather than an outrageous outlier.

This is exacerbated by the drop-out, so to speak, of the middle-market thanks to the entrance and price-setting domination of fast fashion retailers. There is a reason why traditional mall retail brands are dead, and a marked part of the reason is price; the garments being put forth by Abercrombie, for instance, were just way too expensive compared to Forever 21, and yet, they were targeting relatively the same consumer groups.

(Note: There is currently a re-emerging middle(ish) market being pioneered by the likes of Grana and co., but it is still dominated by more expensive prices than the post-Made in China, post-NAFTA, and post-fast fashion market norms. It does, however, represent something of a middle point between fast fashion and high fashion, although not a perfect one for most consumers).

The Flip Side: High Fashion

This phenomenon of shocking prices is not limited to fast fashion retailers and the other mainstream names that have been forced to follow suit in order to compete. For every shockingly low cost garment, you have the “alternative” of a Miu Miu mini dress, which will set you back $7,000, Saint Laurent crystal-encrusted boots that cost $10,000, and some Gucci cotton tees that bear $950 price tags – all of these products can be purchased online.

It should be telling when actress Gwyneth Paltrow, whose lifestyle brand Goop is known for its own uber-expensive products and services, speaks out about the current state of high fashion pricing. In an interview with W magazine last month, Paltrow explained why she launched a collection of “super-flattering, cool basics.” The line “was born out of a frustration for where the price points have gotten in designer clothing,” says Paltrow. “Not that I don’t love Gucci, because I [do], but it is bananas. It is so expensive.”

The prices demanded in connection with high fashion or “premium” offerings are the result of a handful of factors, including the widely-shared mentality that price is often a fair or accurate indicator of quality, and that under this rationale, designer wares and their high costs are automatically indicative of a certain level of quality. This is not always – or even, often – the case, as the price of a garment or accessories includes an array of costs that fall outside of the scope of pure production.

While the cost of labor and materials that go into making garments does dictate the figure on the price tag to a large extent, pricing is not always as straightforward as it may seem, at least not according to industry insiders, including Luke Grana, founder of label Grana. According to Grana, whose label aims to increase pricing transparency, “Luxury t-shirts, for instance, can cost more because they have detailed and expensive trimmings and generally a luxury brand name has a reputation. But what’s not true is the price you pay. Yes, it does cost more to make, but it doesn’t need to cost 6-8 times more.”

Here, Mr. Grana (who does, of course, have at least a slight promotional motive of his own) is referring in part to markups being put forth on behalf of brands, themselves, and by retailers.

Price tags are further extremized by fashion houses’ need to maintain the aura of exclusivity, which is achieved, in part, by consistently raising prices. Consider Louis Vuitton. When faced with logo-fatigue and falling revenues (as a result) several years ago, the Paris-based brand opted to raise the prices of its products – and introduce pricey new products – in an attempt to regain some if its allure. And it worked, just as the 24 anti-laws of marketing predict. One such law: Number 14. “Keep raising the average price of the product range.”

The larger price strategy of fashion’s upper echelon centers even more squarely on the fact that fashion brands can get away with these prices. This is true, in large part, because many of these products, thanks to their purposeful placement of logos and trade dress, serve as outward indicators of status. That is something consumers have been willing to pay for – and pay handsomely for – for a very long time.

In furtherance of the consumption and usage of garments and accessories as status symbols, a high price tag is often a consumer’s friend: When purchasing products meant to inform others of the wearer’s social standing, after all, hefty price tags tend to influence consumers’ opinions of the value of a product.

In short: The price (and consumers’ willingness to pay it) is a reflection – or better yet, a validation – of consumers’ belief that a company’s branding, i.e., its name and various trademarks, are worth that premium.

In much the same way as our culture equates cost to quality, price is used as an indicator of value; this was the key takeaway in a 2008 study put forth by researchers from California Institute of Technology and Stanford University. They found that if brands “slap on a hefty price tag [on a product], our opinion of it tends to go through the roof,” regardless of the actual quality of that product to a large extent.

But this is not a new concept. The answer to why brands can get away with such extreme pricing – on both ends of the spectrum – is one that can be derived somewhat easily from a line that Oscar Wilde included in his play, Lady Windermere’s Fan, A Play About a Good Woman, in 1892. Wilde wrote, the market is full of “men who know the price of everything but the value of nothing.”

Put simply, consumers – with less options in a polarized market of extremes – have become increasingly out of touch with the value garments and accessories (for any/all of the reasons mentioned above), and so, why would they not also be out of touch with the cost.