Whether it be streetwear brands’ penchant for carefully limiting supply to drive demand (and a thoroughly thriving secondary market), millennial-focused brands’ push for community and collaboration, or luxury brands’ practice of walking a line between exclusivity (as driven largely by brand storytelling) and corporatized profitability (the latter of which has been pioneered by the likes of LVMH and Kering, which both maintain brands that would be considered more mass than traditional luxury in nature), it is clear that strategy – and an arsenal of valuable intellectual property rights – is what sells products.

With that in mind, Hermès and its meticulously crafted distribution strategy is worthy of reflection. While the status quo of the fashion industry is very much in flux, with many similarly situated brands busy tapping buzzy creative directors, going (almost) all-in in terms of the digital sphere, including the leveraging of social influencers, in order to reach a larger pool of consumers (i.e., younger consumers), and making shifts in their portfolios and thus, their priorities, Hermès has remained in one of the strongest positions in terms of luxury cache but also in profitability, capital efficiency, and growth/momentum, etc.

According to Hermès’ president and CEO for the Americas Robert Chavez, this is largely tied to the 181-year old luxury stalwart’s retail and distribution strategy. Chavez, speaking at Skift’s Global Forum in September, attributed no shortage of Hermès’ success to its “very limited distribution strategy.” To be exact, Hermès operates only about 300 stores in the world, with just over 30 brick-and-mortar outposts in the U.S., and its shoppable website.

“Our strategy of keeping a very limited distribution has really worked very much in our favor,” according to Chavez.

After all, he notes, “People want things that not a lot of people can get. I mean, that’s what it’s like in the luxury world and continues to hold true. Once something becomes very, very saturated that luxury customer doesn’t really want that anymore.”

As for the younger demographic of consumers, who are influenced by their communities (i.e., “We adopt a [brand] because our friends are already there,” as strategist Ana Angelic put it), come to dominate an increasingly large percentage of the market, the demand for Hermès is there. This younger group of consumers – the ones that are currently helping Gucci and its parent company Kering to break records in terms of revenue and growth – are actively being introduced to luxury-level products by the rise of pre-owned fashion. Luxury consignment site The RealReal, for instance, revealed this summer in its mid-year report that Hermès is the fastest-growing brand among millennials, growing 71 percent among the 18-34 demographic.

Chavez says it is critical that Hermès remain relevant “in a fast-changing retail world,” where brands are busy vying for the coveted millennial and Gen-Z consumers. It is doing so by way of its Instagrammable popup shops, and the consistent introduction of more entry-level consumer-recruiting products, such as footwear, which “has become a recruitment category for us in a very very big way. It’s one of our fastest-growing businesses.”

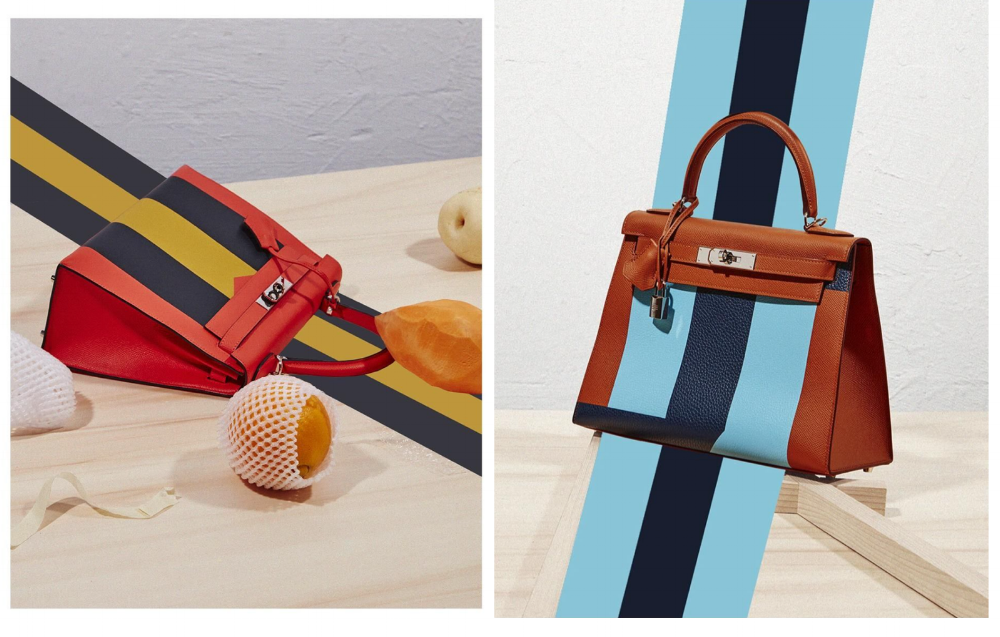

Still yet, Hermès is working diligently to inject newness into its more staple luxury offerings. “We have classics of course,” per Chavez, “but every six months, our store directors, every store director from all over the world goes to Paris, twice a year, to buy the next season’s product.”

“Very few companies,” he boasts, “will send three-hundred individual store directors to Paris to buy for a week for their store.”