Hermès has doubled-down on its claims against the maker of similarly-named non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”), amending the complaint that it first filed against MetaBirkins creator Mason Rothschild in January. In the amended complaint that it lodged with the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York on Wednesday, Hermès again asserts that Rothschild is running afoul of federal trademark law by way of his MetaBirkins collection of NFTs and his continued use of the term “MetaBirkins” as a trademark, as he is confusing consumers about the source and/or nature of the digital artworks tied to the NFTs, while also diluting the “distinctive quality” of Hermès’ world-famous handbags and its branding.

Mirroring the claims that it made in its initial complaint early this year, Hermès alleges that in creating the collection of 100 “MetaBirkins” NFTs, Rothschild is looking to “get rich quick […] by appropriating the trademark METABIRKINS to identify a business that creates, markets, sells, and facilitates the exchange of investable, digital assets known as [NFTs].” In using “METABIRKINS as the trade name for his business and a collection of NFTs,” Hermès claims that Rothschild has “simply rip[ped] off [its] famous BIRKIN trademark by adding the generic prefix ‘meta’ to the famous trademark BIRKIN,” which Hermès says “simply means ‘BIRKINS in the metaverse.’”

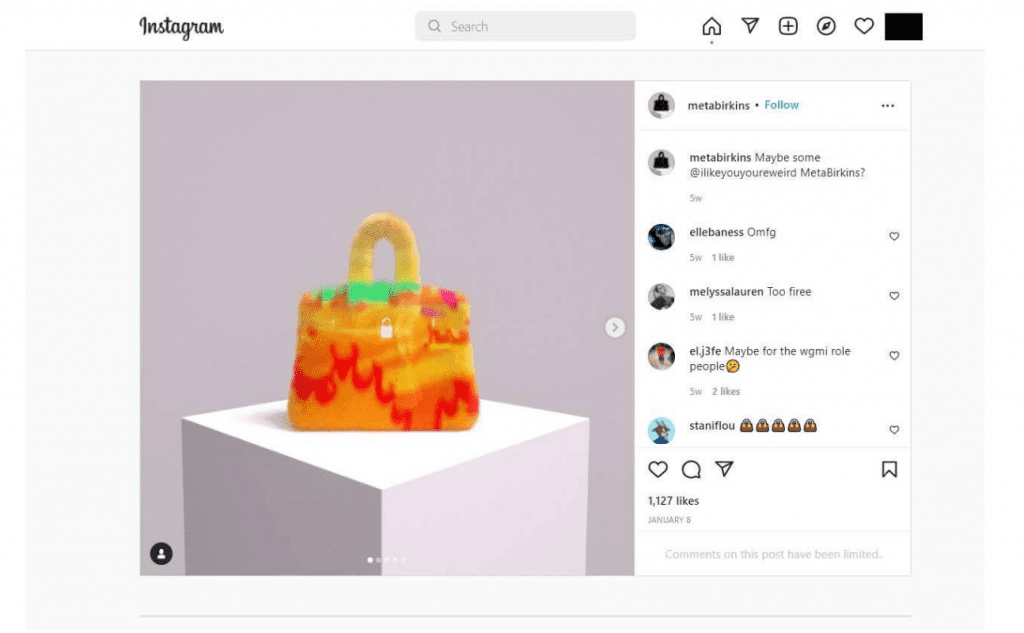

Not only has Rothschild co-opted the Birkin trademark, Hermès alleges that he has made use of other Hermès trademarks, such as the Birkin bag trade dress, as part of “a calculated attempt to explicitly mislead the public into believing Hermès authorized his METABIRKINS business.” And it worked, according to counsel for the French luxury goods brand, which claims that Rothschild’s adoption and use of METABIRKINS has “explicitly misled the general public as to whether Hermès authorized [his] business and collection of NFTs.”

Specifically, Hermès alleges that the language that Rothschild uses to promote the MetaBirkins is likely to confuse consumers. In addition to “implying that the METABIRKINS collection of NFTs are actually ‘Birkin NFTs,’” Hermès claims that Rothschild “confuses readers by claiming on his website and at point of sale that the METABIRKINS collection of NFTs are ‘a tribute’ to the BIRKIN handbag.”

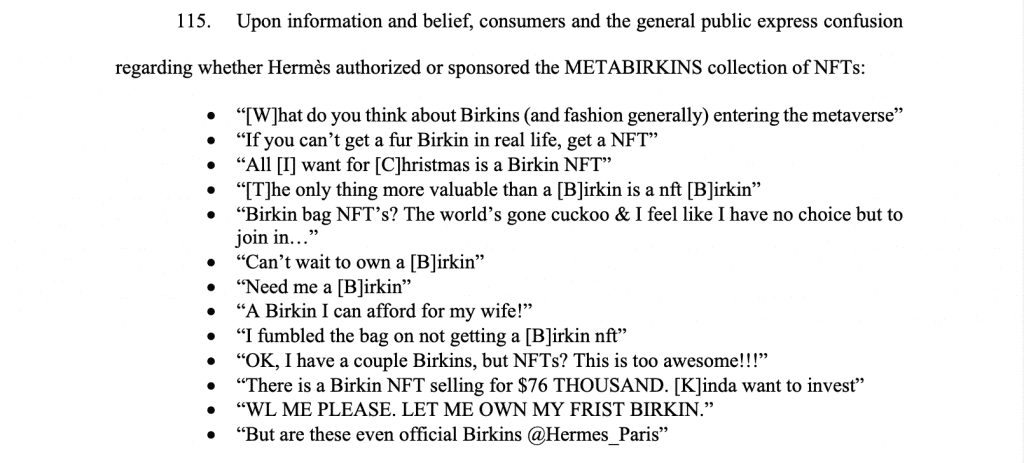

That potential for confusion has, in fact, translated to the public, per Hermès. After the initial launch of the METABIRKINS collection of NFTs in December, a number of media outlets, including Elle, L’Officiel, and the New York Post reported that Hermès was directly involved in the creation/launch of the METABIRKINS collection. Hermès similarly points to an array of comments from social media, which it says show that consumers have also been confused as to whether Hermès is involved in creating and/or offering up the MetaBirkins NFTs. Such confusion is not surprising given the prices at play, per Hermès. “As of January 2022, total volume of sales for the METABIRKINS collection of NFTs surpassed $1.1 million, with a floor price of $15,200, and the highest sale at $45,100,” Hermès states in its complaint, arguing that in light of “these prices and the marketplace confusion, consumers view the METABIRKINS collection of NFTs as BIRKINS in the metaverse.”

Beyond that, Hermès claims that consumers are likely to be confused about the nature of the MetaBirkins NFTs since they “see a wide variety of brands, including luxury fashion brands, exploiting the NFT space,” including in collaboration with third-party artists, and thus, “would expect that NFTs featuring famous brands are affiliated with those brands, or wonder why the famous brands are permitting such dilutive use of their valuable assets and think less highly of them.”

MetaBirkins: Use as a Trademark

Setting the stage for its trademark infringement claims, while also seemingly seeking to stomp out the fair use claims that Rothschild’s counsel will make in response to its amended complaint, Hermès asserts that Rothschild is using the MetaBirkins name in a trademark capacity. (Trademark infringement not only requires likelihood of confusion, but more fundamentally, requires that the defendant is using the mark in a trademark capacity. At the same time, Rothschild’s alleged use of the MetaBirkins name as an indicator of source of his own (virtual) goods could also stand in the way of a successful First Amendment defense.)

According to Hermès, examples of Rothschild’s use of “MetaBirkins” as an indicator of source of his offerings, include “identifying his first collection of NFTs using the METABIRKINS trademark,” adopting “METABIRKINS for his Twitter handle, Instagram account name, and Discord channel,” operating the “MetaBirkins.com” website that “advertises and promotes the sale of the NFTs in his METABIRKINS collection,” and advertising “his NFTs using advertising slogans incorporating his METABIRKINS trademark and the BIRKIN trademark: NOT YOUR MOTHER’S BIRKIN, MintAMetaBirkinHoldAMetaBirkin, and MetaBirkinsGonnaMaketIt.”

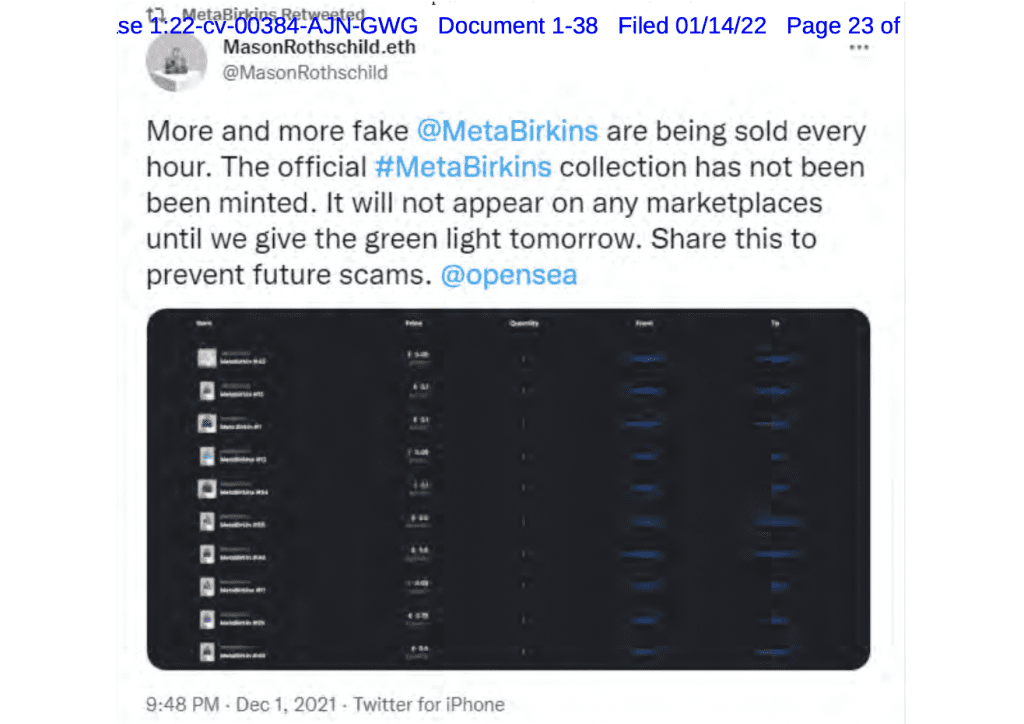

“The fact that [Rothschild] has adopted and is using METABIRKINS as a trademark is evident not only from his pervasive use of METABIRKINS as his brand and trade name for his NFT projects, but also from the proprietary rights that he is claiming in the METABIRKINS brand,” Hermès asserts, pointing to Rothschild’s “repeated complaints” of the presence of “fake” and/or “counterfeited” MetaBirkins on various NFT marketplaces.

Ultimately, Hermès claims that Rothschild is “trying to ‘create the same kind of illusion that [the Birkin] has in real life as a digital commodity,’” and in doing so, he has experienced “great financial success in a matter of weeks” – albeit this success “no doubt […] arises from his confusing and dilutive use of the BIRKIN word mark in association with other famous Hermès trademarks.” All the while, Hermès argues that Rothschild is looking to “immunize himself from the legal consequences of his appropriation of the BIRKIN word mark and Hermès’ famous trademarks to build his NFT business by proclaiming that he is solely an artist.”

While a digital image connected to an NFT “may reflect some artistic creativity, just as a t-shirt or a greeting card may reflect some artistic creativity,” Hermès contends that “the title of ‘artist’ does not confer a license to use an equivalent to the famous BIRKIN trademark in a manner calculated to explicitly mislead consumers and undermine the ability of that mark to identify Hermès as the unique source of goods sold under the BIRKIN mark.”

“Calling [Rothschild’s] marketing strategy ‘art’ is a ruse and must not be sanctioned,” per Hermès, which states that Rothschild “is stealing the goodwill in [its] famous intellectual property to create and sell his own collection of NFT products and run a business that promotes speculation in NFTs.”

Moreover, Hermès claims that while it “has not yet minted and sold its own NFTs,” it, nonetheless, “has the right to do so at the time and manner of its choosing.” Unless he is enjoined by this court, Hermès contends that Rothschild “will continue to advertise and sell NFTs under the METABIRKINS brand, build a company offering a range of virtual products and services under the METABIRKINS brand, and ultimately, preempt Hermès’ ability to offer products and services in virtual marketplaces that are uniquely associated with Hermès and meet Hermès’ quality standards.”

The need for injunctive relief is seemingly heighted by the fact that in addition to releasing 100 MetaBirkins NFTs, Rothschild has “expanded his use of the METABIRKIN trademark to promote his other NFT ventures.” For instance, Hermès states that “one of [Rothschild’s] advertising campaigns was called ‘Build-A- MetaBirkin,’” in which he “encouraged followers of the METABIRKINS Discord channel to ‘Build a MetaBirkin using household materials’ and to submit their designs on a separate Discord channel.” Thereafter, Rothschild “publish[ed] the most popular submissions within the METABIRKINS Discord channel” and on the MetaBirkins social media accounts.

Again, as in its initial complaint, Hermès sets out claims of federal and common law trademark infringement, false designation of origin, trademark dilution, cybersquatting, and injury to business reputation and dilution under New York General Business Law. In terms of remedies, the company is seeking monetary damages, including Rothschild’s profits, and injunctive relief to bar him from making further use of its trademarks, such as by “using any reproduction, copy, counterfeit, or colorable imitation of Hermès’ Federally Registered Trademarks to identify any goods or the rendering of any services not authorized by Hermès.”

Among other things, Hermès has asked the court to require Rothschild to transfer the MetaBirkins.com domain to it and to “deliver up for destruction to Hermès all unauthorized products and advertisements in his possession or under his control bearing any of Hermès’ Federally Registered Trademarks or any simulation, reproduction, counterfeit, copy or colorable imitation.”

An Interesting Takeaway: Given the novelty that comes with NFTs and trademark claims in this space, there are unanswered questions about how courts will treat trademarks in the metaverse, and specifically, whether they will identify a potential gap for trademark holders when it comes to their rights in marks in the virtual world. Here, it will be interesting to see how the court treats Hermès’ robust “real world” rights in the Birkin mark and trade dress in the virtual world since the brand does not offer up NFTs or virtual goods of its own. (There is, of course, no saying that such a gap necessarily exists or that Hermès rights in the Birkin mark for use on physical goods and in connection with digital services, such as e-commerce, would not be sufficient to police unauthorized and allegedly infringing uses, such as the MetaBirkins.)

While Hermès does not explicitly address this potential gap, it does make a compelling argument in which it likens the value of its Birkin bags to the value of NFTs. In diving into the nature of NFTs, which it did not do in its initial complaint, and which is a nod to the work that plaintiffs will undoubtedly have to do to educate courts about the workings of this relatively novel technology, Hermès appears to compare the investment quality of its bags to that of NFTs.

Specifically, Hermès states that “because NFTs can easily be sold and resold while the transaction history is recorded on the blockchain, NFTs are viewed as investable assets which can store value and increase even increase in value over time, just like Hermès’ BIRKIN handbags.” In making this argument, Hermès notes that Birkin bag “has been recognized as one of the best investments any person can make with its increasing value beating returns from the stock market and even gold,” and cites reports about the return on investment that Birkin bags bear, citing a 2016 report that found “the annual return on a Birkin [handbag] was 14.2% compared to the S&P [500] average of 8.7% a year and gold’s down 1.5%.”

The case is Hermès International, et al. v. Mason Rothschild, 1:22-cv-00384 (SDNY).