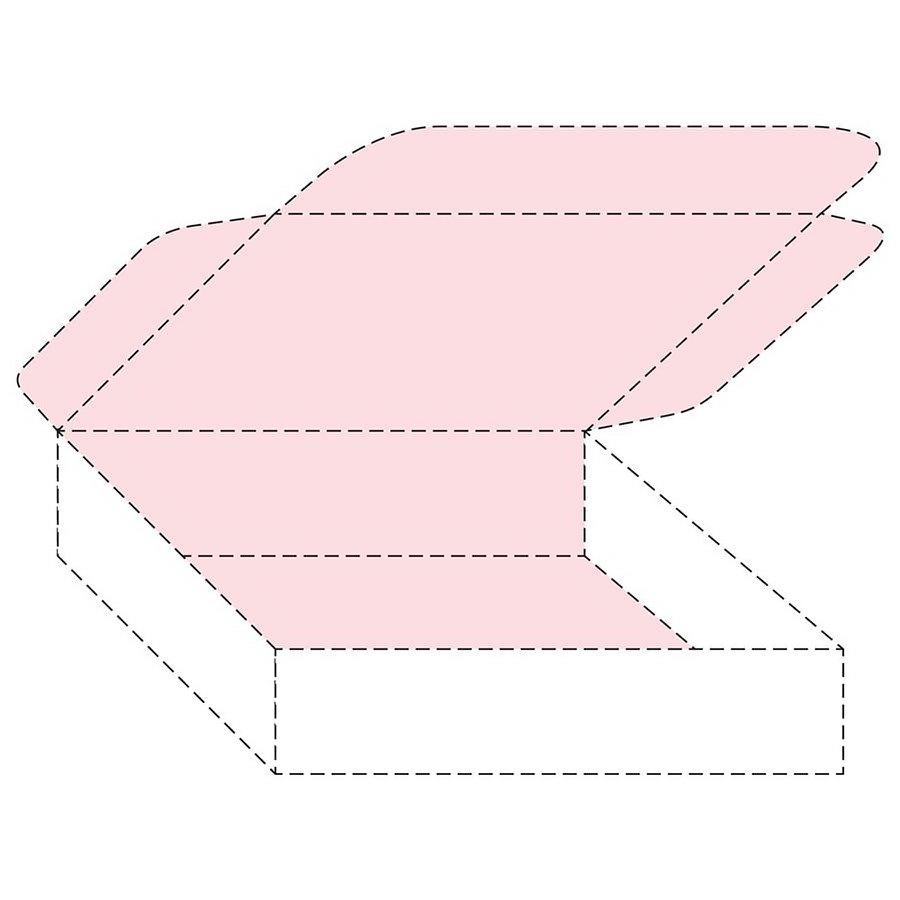

Glossier claims that when consumers see a box with a millennial pink interior, they automatically link it – and the products inside – with its brand. Looking beyond its most immediate branding, Glossier – which nabbed a $1.2 billion valuation last year after raising $100 million in series D funding – applied to register two iterations of its product packaging with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) in March 2019: its millennial pink-lined boxes and similarly pink bubble wrap-lined zip-lock pouches for use in connection with its marketing and sale of “cosmetics; makeup; [and] skincare products.”

Asserting that “there is no utilitarian, functional, economic, or competitive advantage to the color pink as applied to the inner surface of boxes,” and citing its pattern of consistently using the pink-lined boxes for the past five years, Glossier essentially claims that its specific use of millennial pink on the interior of packaging boxes acts as a trademark – and identify the source of the products – in much the same way that a brand name or logo does. And with that it mind, the buzzy beauty unicorn is pushing for a registration for its use of “the color pink as applied to the inner surface of portions of boxes that contrast with the color of the rest of the boxes” in connection with the sale of skincare and cosmetics.

The concept of a color – or better yet, the specific use of a specific color – as a trademark is not unheard of; Tiffany & Co. and Christian Louboutin, among others, maintain valid trademark rights in their proprietary uses of certain colors. Nonetheless, the USPTO has been a bit hesitant (which is not uncommon when it comes to quest to protect uses of colors), and preliminarily refused to register Glossier’s mark in August on that basis that the use of the color pink on the inside of a box is decorative and thus, does not function as a trademark. According to the USPTO, consumers are not likely “to perceive the color pink as identifying the origin of [Glossier’s] goods; but rather, they will perceive the colors as decorative features … because they are accustomed to encountering various colors, including pink, on various packaging for cosmetics and beauty care goods.”

Glossier has responded to the USPTO’s Office Action in late February and refined the language of the trademark description to limit its scope from pink-lined boxes generally to the “color pink [as applied to the inner surface of portions of boxes] so that it contrasts with the rest of the box.”

Additionally, the brand’s counsel asserted, among other things, that the pink-lined box mark has established the necessary secondary meaning to function as a trademark – given “the extensive evidence … that relevant consumers immediately recognize [its unique and distinctive use of] the color pink as applied to only the interior of a box indicates that the cosmetics and skincare products originate from Glossier and not from any other source.”

While it appears that Glossier has successfully made its case for why its mark should be registered, as the USPTO examiner states in a March 19 letter that its previous refusal on the basis of failure to function has been “obviated by sufficient Section 2(f) claim,” there is a new issue at play. The USPTO has suspended the application.

In a letter last month, the USPTO alerted Glossier that its application has been put on hold, so to speak, for the time being because there is a pending trademark application that “has an earlier filing date or effective filing date than [Glossier’s] application” that, if registered, may cause the USPTO to refuse to register Glossier’s mark “because of a likelihood of confusion with the registered mark.” (The USPTO will not register a mark that conflicts with – i.e., is confusingly similar to – a mark that is either registered or currently pending).

What is at the center of that other pending application? A word mark for “PINKBOX” for use on cosmetics; “computer application software for mobile phones namely, software for providing episodic television and virtual reality; downloadable films and virtual reality content featuring dramatic and comedic storylines”; “comic books; graphic novels; series of fiction novels”; and “Entertainment services, namely, arranging social entertainment events in which users can participate in virtual reality viewings; entertainment services, namely, virtual reality arcade services.”

As it turns out, Brandi-Ann Milbradt beat Glossier to the punch in filing an application for “PINKBOX” in November 2016, and while the USPTO previously gave preliminary approval for the registration of the mark (by way of a September 2018 notice of allowance), there is one lingering issue at play: Milbradt – a producer, who was tapped by Refinery29 in 2015 “to spearhead its effort to generate original video content” – has not been able to show that she has used the mark in connection with all of the goods/services she listed on her application.

While Milbradt has provided the USPTO with evidence that she has used the mark in connection with “entertainment services,” she still needs to do the same for the other classes of goods/services listed in her application in order for the mark to be registered for those classes. (Actual use of a mark in commerce is a pre-requisite to trademark registration in the U.S.).

Interestingly, while Glossier’s pink-lined packaging and the “Pinkbox” mark are quite different from a practical perspective (one is a word mark and the other is product-packaging trade dress), the USPTO explicitly states that “it is not required that the marks and the goods/services be exactly the same” in order for there to be a conflict. Instead, “it is sufficient if the marks are similar” – in terms of appearance, meaning, and/or sound – “and the goods and or services related such that consumers would mistakenly believe they come from the same source.”

That is likely the case here since while the marks, themselves, are not identical in nature, both parties list cosmetics as goods on their applications. Moreover, as trademark counsel Cynthia Clarke Weber states, “Trade dress creates a visual impression which functions like a word trademark,” so much so that “the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed in Two Pesos and Qualitex there is really no difference between a word trademark and a visual trademark except that a word mark may be spoken while trade dress and color per se must be seen to make a commercial impression.’

As a result of the pending “Pinbox” mark, the USPTO will wait to see whether Milbradt will be able to show use of her mark on the remaining goods/services at play, and says that it “will periodically check [Glossier’s] application to determine if it should remain suspended.”