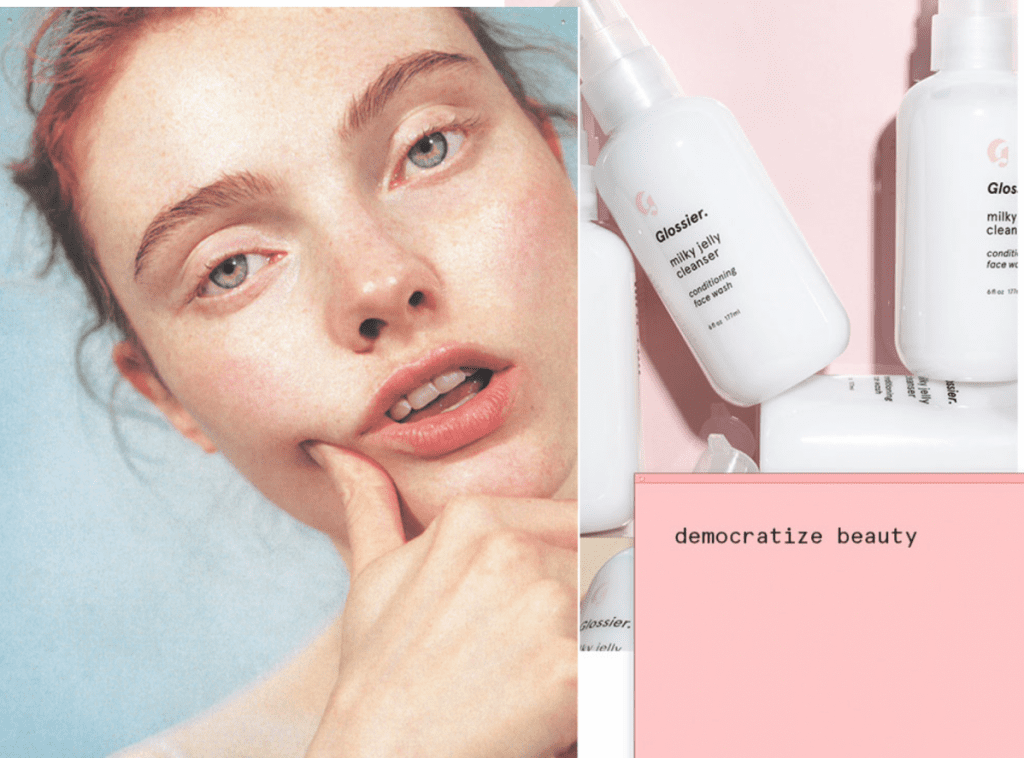

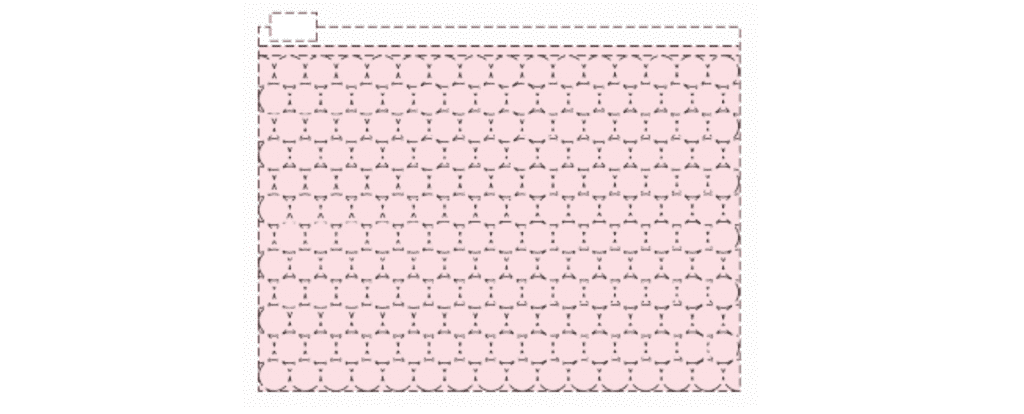

For every order that a consumer makes on Glossier’s e-commerce site or in its small network of brick-and-mortar outposts (pre-COVID, that is), the products come in a millennial pink ziplock pouch. In much the same way as the 6-year old brand’s stylized “G” logo and its catchy product names – from the cult-favored “Boy Brow” eyebrow product to its “Balm Dotcom” lip salve – have become trademark elements of the billion dollar brand, so, too, have certain aspects of its packaging. That is precisely what Glossier argued when it filed two trademark applications in the spring of 2019 for its inherently-Instagrammable packaging.

A little over a year after Glossier filed applications for those packaging-specific trademarks, it has been issued a registration for one of them. On Tuesday, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) handed Glossier a registration for the pink bubble wrap pouch that the venture capital-magnet has been using since October 2014 in connection with an array of cosmetics. Specifically speaking, the mark consists of a certain shade of the color pink – presumably Pantone’s 705C hue – “as applied to bags featuring lining of translucent circular air bubbles and a zipper closure.”

The registration for the pink pouch comes after Glossier – which was born on the back of founder Emily Weiss’ popular beauty site, Into the Gloss, and has since gone on to nab a $1.2 billion valuation (as of Match 2019) – faced pushback from the trademark office, which preliminarily responded to Glossier’s application by refusing to register the mark. In a July 2019 Office Action, USPTO examining attorney Michelle Dubois stated that while she could not find any conflicting marks in the trademark office’s database of registered and pending marks that would stand in the way of the registration of Glossier’s mark, she, nonetheless, took issue with the pink pouch for a couple of key reasons.

Functional & Non-Distinctive?

For one thing, Dubois asserted that the pink pouch was ineligible for registration because it is “a functional design for such packaging,” which is problematic, as functionality is an absolute bar to registration. (Glossier was able to overcome this aspect of the refusal by submitting a new trademark drawing, and “clarifying that the air bubbles and the packaging itself are not claimed as features of the mark,” which exclusively consists of “the claimed color pink as applied to a very particular type and configuration of product packaging.”)

More than that, Dubois argued that the mark “consists of a nondistinctive configuration of packaging for the goods,” making the ziplock pouch incapable (on its face) of identifying the source of the products at play. This was due, at least in part, to the fact that bubble wrap lining is a common feature of “goods that are going to be in transit or are going to be shipped,” per Dubois, and Glossier’s use of “the color pink … on such pouches is not unique.”

With that in mind, Dubois preliminarily refused the mark on the basis that “consumers will not immediately consider [Glossier’s] packaging as an indicator of source.”

“Glossier’s Pink Pouch”

On the heels of the USPTO’s Office Action, counsel for Glossier filed a 252-page response in January, in which it set out to establish that the pink pouch does, in fact, serve to indicate the source of the products associated with it. The bulk of that filing centered on the brand’s assertion that its use of the color pink on its packaging has acquired distinctiveness, namely “based on five years’ use of the mark, as well as extensive evidence that when the relevant consumers see the color pink on a bubble-lined, zip-top pouch, they immediately recognize it as Glossier’s Pink Pouch.”

To prove that, Glossier provided third-party media articles about the company that mention its use of the pink pouch. It also pointed to examples of consumer social media posts featuring the pink pouch, which Glossier says “demonstrate that many consumers already associate the Pink Pouch with [it], [while also] serving to educate even more consumers and reinforce the association between the Pink Pouch and Glossier.”

The brand asserted that the pink pouch “has been used continuously since at least as early as 2014 [by Glossier], and in 2018, the revenue generated by sales of goods [that included use of] the mark amounted to more than $100 million.” And all the while, the company says that it “has consistently promoted the Pink Pouch by featuring it on the Glossier website, in numerous marketing emails, in social media posts, and even on New York City subway ads.”

With such an “abundance of evidence” in mind, Glossier asserts that “the color pink, as applied to bags featuring lining of translucent circular air bubbles and a zipper closure, has acquired source-indicating significance in the minds of the relevant consumers.” In other words, “when consumers see the Pink Pouch, they immediately recognize it as emanating from Glossier,” and thus, the mark should be registered. As of August 25, the USPTO agreed, issuing a registration to Glossier for the mark.

It Makes Sense

Beyond being a clear demonstration of what brands are endeavoring to do in a branding sense in order to help set themselves apart in the minds (and wallets) of consumers in an inherently digital age, Glossier’s successful quest to earn a trademark registration for its use of the specific color pink on specific product packaging is interesting for a whole host of reasons, including what this potentially says about the role that social media can play in brand building (and showing secondary meaning). This is particularly relevant for young companies that do not have decades of continuous use of a mark and tens of millions of dollars in sales to point to, which is precisely what 125-year old Barbour, for instance, had in 2018 when it filed an application for registration with the USPTO for its famed wax jacket.

Speaking of social media, University of New Hampshire School of Law professor Alexandra J. Roberts says that it is noteworthy that Glossier’s evidence of secondary meaning included not only its own social media posts and those from paid influencers in its filing as evidence of secondary meaning, but also made use of examples of individual consumers posting photos on social media that feature the pouch. Such consumer-generated content “both reflects and contributes to the acquired distinctiveness” of the pink pouch trade dress, and overall, amounts to evidence that she says is “really strong.”

Beyond the sheer power of social media and influencer marketing, Roberts sees “Glossier’s speedy success with the registration” as reflecting the power of look-for advertising when it comes to establishing secondary meaning in the minds of consumers. “In assessing whether trade dress has acquired distinctiveness,” a registration pre-requisite for marks that are not inherently distinctive, “the USPTO and courts often want to see advertisements that highlight and play up the particular [trade dress] feature for consumers.” She says “that type of marketing does not always explicitly include language like ‘look for___ ,’ but may take the approach that points to the feature and directs consumers to pay attention to it as a source indicator.”

“That is what Glossier did by featuring the pink pouch on its website, in marketing emails, in social media posts, and in subway ads.”

Ultimately, Glossier’s process here, which has seen it “decide on packaging of a notable color and notable ‘translucent circular’ air-bubble design, identifiable at a glance, and endeavor to get it in front of as many eyes as possible, as often as possible,” as trademark attorney and former USPTO trademark examining attorney Ed Timberlake characterizes it, is right up the alley of the U.S. trademark statute … even if the mark at play is not a traditional wordmark or logo. In other words, many marks that people tend to characterize as non-traditional are actually “playing entirely traditional cognitive roles under the Lanham Act,” and that is what is going on here.

“At least as I read it, the Lanham Act [treats trademark rights] less like real estate,” or property, “and more akin to cognition.” With that in mind, “The point is not simply to make claims but to make an impression,” he says.

Timberlake states that it is likely that “an aggressive social media campaign behind a symbol less capable of distinguishing the source of goods [than Glossier’s pouch] may well have made less of an impression on consumers (potentially leading consumers to make less of a connection with applicant’s goods) and may well have had little but litigation to fall back on in an effort to carve out cognitive space.”

Viewed in this light, he says that Glossier’s approach – which has seen it adopt a symbol, notably, colored bubble-bags, by which its goods may be distinguished from the goods of others – “seems to make a great deal of sense.”