This spring, Glossier filed two trademark applications with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). It turns out, Glossier is looking to register a couple of new marks with the national trademark body, which – if granted – will join the growing arsenal of registrations held by the 5-year old beauty unicorn that was spawned from entrepreneur Emily Weiss’ popular Into the Gloss blog. However, unlike its existing registrations for its name, its stylized “G” logo, and many of its individual product names – from Balm Dotcom to Boy Brow, these two new(er) applications are a bit different.

Looking beyond its most immediate branding, Glossier – which nabbed a $1.2 billion valuation early this year after raising $100 million in series D funding – applied to register two iterations of its product packaging: its millennial pink-lined boxes and similarly pink bubble wrap-lined zip-lock pouches for use in connection with its marketing and sale of “cosmetics; makeup; [and] skincare products.”

By asserting rights in these things, Glossier is essentially claiming that in much the same way that consumers link the word “Glossier” with its brand, they make a connection in their minds when they see boxes with pink interiors and pink bubble wrap pouches. In other words, those two forms of packaging function as trademarks – or better yet, trade dress – of the Glossier brand.

In its preliminary review of the two applications this summer, the USPTO refused to register both marks, at least preliminarily. According to a USPTO examining attorney, the bubble wrap trademark is problematic, as it “appears to be a functional design … with a specific utilitarian advantage,” namely, the bubble wrap serves “a protective feature for the goods being stored in the interior.” That is an issue, as functionality is an absolute bar to registration.

Additionally, the examining attorney stated in the July 2019 letter that assuming that the pink bubble wrap is not entirely functional, it cannot be registered unless Glossier can show that as a direct result of its “extensive use and promotion of the [pink bubble wrap pouch]” consumers have come to “directly associate the [pouch] with [Glossier] as the source of goods” associated with it.

This might be difficult for Glossier to prove, the USPTO notes. Not only is “the use of bubble wrap lining a common feature of “goods that are going to be in transit or are going to be shipped,” but Glossier’s use of “the color pink … on such pouches is not unique.” According to the USPTO, a “toiletry case from victoriassecret.com is [also] sold with bubble wrap lining.”

(While novelty is not a requirement for trademark rights like it is for say, patents, it is relevant here, nonetheless, because trademark rights depend on the ability of consumers to link a trademark to a single source (or brand). So, if many brands are using a design feature, such as pink bubble wrap pouches, there is less of a likelihood that consumers will link one brand’s use of that feature to that single brand.)

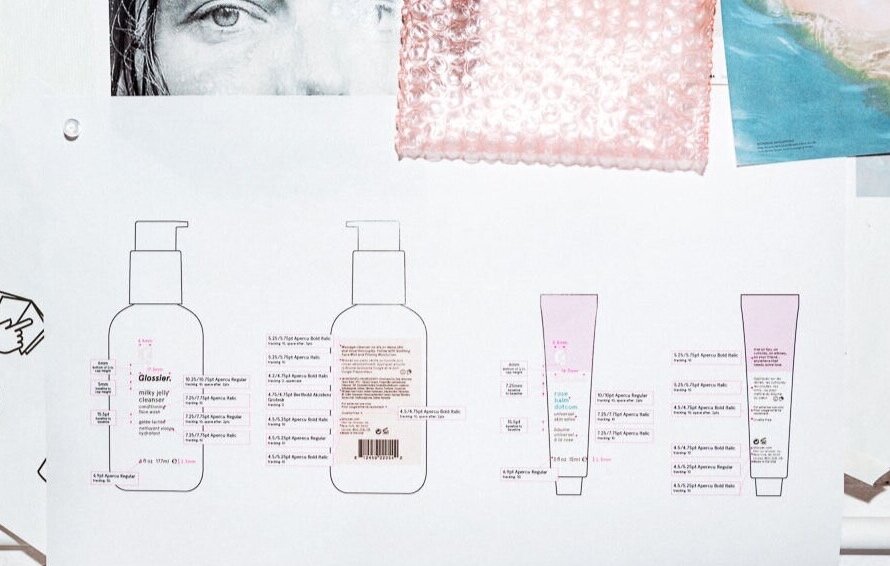

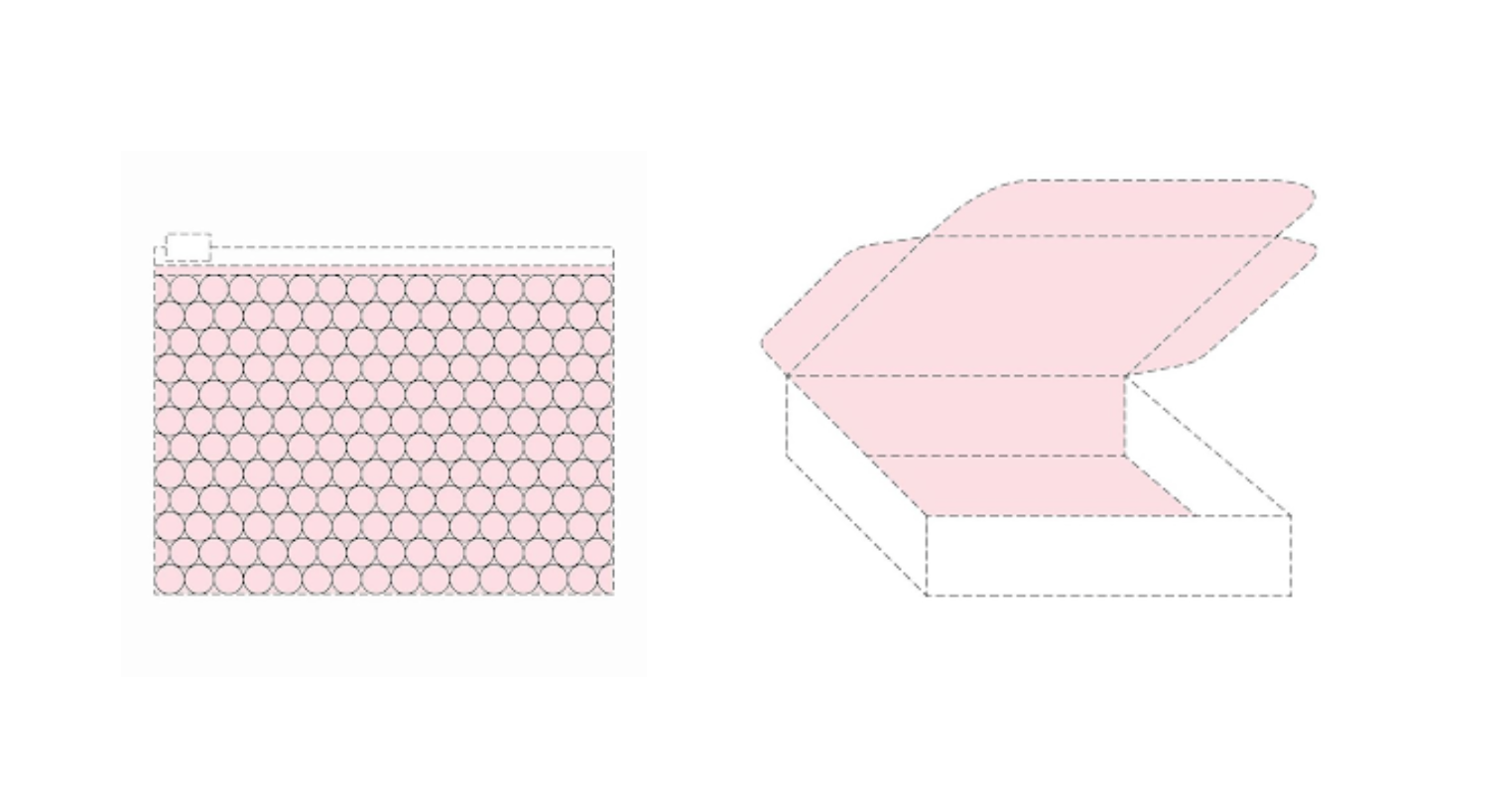

Glossier’s bubble wrap pouch (left) & its pink interior box (right)

Glossier’s bubble wrap pouch (left) & its pink interior box (right)

In terms of Glossier’s application for boxes of “various sizes” that have a pink-colored interior, the USPTO asserted in a separate letter in August that the mark is not registrable because, among other things, it is decorative and thus, does not function as a trademark – aka it does not serve to identify the source of the boxes or the products inside the boxes. According to the USPTO, consumers are not likely “to perceive the color pink as identifying the origin of [Glossier’s] goods; but rather, they will perceive the colors as decorative features … because they are accustomed to encountering various colors, including pink, on various packaging for cosmetics and beauty care goods.” The examining attorney points to pink-hued packaging from Sephora, Kylie Cosmetics, and Petit Vour, among others brands, as examples.

Glossier’s counsel now has the opportunity to respond to the USPTO’s concerns by submitting evidence and arguments in support of registration for the two marks.

It is worth looking beyond Glossier’s individual applications to the larger evolution in branding that they represent, particularly when it comes to direct to consumer (“DTC”) brands, i.e., ones that sell products directly to consumers without the help of third-party retailers. With the rise of the DTC model – which has seen the rapid rise of billion dollar-plus brands, such as Glossier, Warby Parker, Casper, and Harry’s, just to name a few – has come a push by those brands (and others) to “invest more time, money and effort” in the visual elements of their products compared to what has generally proven to be the status quo for many of the companies that came before them.

This increased emphasis on product presentation vis-à-vis packaging makes sense for digitally-native DTC companies because for them, a product’s packaging and even its configuration, itself, is in many ways “the store front, experience, service and product,” as business site Raconteur stated in a packaging-specific white paper this spring.

For Glossier, in particular, the focus on – and attempt to federally register – its product packaging makes sense for a host of reasons. For one thing, with a core audience of millennial and Gen-Z consumers – who are 3 times more likely than prior generations to discover new skincare/cosmetics brands and products on social media – it follows that the aesthetic and visual appeal of the brand would play a central role in consumers’ discovery process, and thus, it makes sense that Glossier “designed its chic pink-and-white packaging with the visually obsessed Instagram set in mind,” as AdWeek put it.

Add to that the fact that despite maintaining two permanent brick-and-mortar locations, as well temporary pop-up shops, the 5-year old company says that “most of its products” are, in fact, “purchased online by younger consumers who often follow the brand on Instagram and other social-media channels,” according to the Wall Street Journal. Still yet, e-commerce purchases of Glossier’s products – along with those of other digitally-native beauty, fragrance, and skincare brands – often occur without so much as “a swatch or a sniff,” as beauty writer Cheryl Wischhover aptly noted earlier this year. As such, “really good branding is a big part of why” many of Glossier’s $100 million-plus in sales in 2018 took place. And an essential part of that branding is the packaging and configuration of products, themselves.

The increased focus on and significance of packaging, especially in the DTC space, comes as the nature of branding, itself, continues to evolve. Traditionally, branding has largely consisted of a company’s name, its logo, maybe staple style names, and the like. But, as Glossier clearly demonstrates, for a growing number of brands, product packaging is becoming just as essential to the making – and marketing – of products and services, while also proving a critical element in terms of how consumers are interacting with (unboxing videos, anyone?) and identifying brands in the modern market.

In other words, brand names and logos are not the only identifiers of source that brands are pushing in an effort to entice young – often traditional-advertising-averse – consumers, especially in the crowded social media ecosystem.

Packaging, if done right, can function in just the same way – or potentially, even more enticing (and thus, efficient) ways – than conventional trademarks like a brand name or logo by enabling consumers to connect a product and its packaging with a single source, and in the process, communicating important messaging to consumers about the brand’s reputation, values, and other core identity elements.

That level of consumer recognition and embodiment of goodwill (as it’s referred to in a legal context) is valuable and that is precisely why brands are seeking to protect it just as they would a name or logo, Glossier included.