The European Union reached a provisional agreement on Friday to regulate artificial intelligence, with negotiators agreeing on harmonized rules “to ensure that AI systems placed on the European market and used in the EU are safe and respect fundamental rights and EU values.” In a statement on Friday, the European Council said that the AI Act is “a flagship legislative initiative with the potential to foster the development and uptake of safe and trustworthy AI across the EU’s single market by both private and public actors.” The essential EU decision-making body noted that “the main idea is to regulate AI based on the latter’s capacity to cause harm to society following a ‘risk-based’ approach: the higher the risk, the stricter the rules.”

Calling the AI Act “the first legislative proposal of its kind in the world,” the Council asserted that it “can set a global standard for AI regulation in other jurisdictions, just as the GDPR has done, thus promoting the European approach to tech regulation in the world stage.”

Among some of the points worth noting …

Defining AI: To ensure that the definition of an AI system provides sufficiently clear criteria for distinguishing AI from simpler software systems, the provisional agreement aligns the definition with the approach proposed by the OECD. That definition is as follows: “An AI system is a machine-based system that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that [can] influence physical or virtual environments. Different AI systems vary in their levels of autonomy and adaptiveness after deployment.”

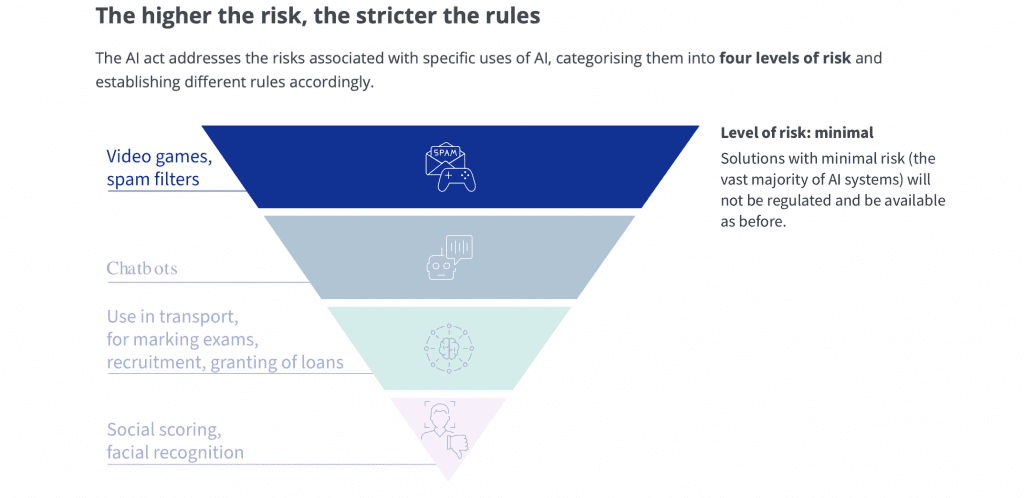

Risk-based approach: The new rules will be applied directly across all EU Member States and will follow a risk-based approach, in which risk level is defined as …

(1) Minimal risk: The vast majority of AI systems fall into the category of minimal risk. Minimal risk applications – such as AI-enabled recommender systems or spam filters – will benefit from a free-pass and absence of obligations, as these systems present only minimal or no risk for citizens’ rights or safety.

(2) Limited risk(s): AI systems that present only limited risks will be subject to very light transparency obligations, such as disclosure that their content was AI-generated, so that users can make informed decisions concerning further use.

(3) High-risk: AI systems identified as high-risk will be required to comply with strict requirements, including risk-mitigation systems, high quality of data sets, logging of activity, detailed documentation, clear user information, human oversight, and a high level of robustness, accuracy, and cybersecurity. Examples of such high-risk AI systems include certain critical infrastructures for instance in the fields of water, gas, and electricity; medical devices; systems to determine access to educational institutions or for recruiting people; or certain systems used in the fields of law enforcement, border control, administration of justice and democratic processes. Biometric identification, categorization, and emotion recognition systems are also considered high-risk.

(4) Unacceptable risk: For some uses of artificial intelligence, the risks are deemed unacceptable, so these systems will be banned from use in the EU. These include cognitive behavioral manipulation, predictive policing, emotion recognition in the workplace and educational institutions, and social scoring. Remote biometric identification systems such as facial recognition will also be banned, with some limited exceptions.

General purpose AI systems & foundation models: Originally designed to mitigate the dangers from specific AI functions based on their level of risk, from low to unacceptable, the AP recently reported that lawmakers “pushed to expand it to foundation models, the advanced systems that underpin general purpose AI services like ChatGPT and Google’s Bard chatbot.” Specifically, the EU Council states that new provisions have been to the provisional rules to consider “situations where AI systems can be used for many different purposes (general purpose AI – or ‘GPAI’), and where general-purpose AI technology is subsequently integrated into another high-risk system.”

“The provisional agreement also addresses the specific cases of GPAI systems,” according to the Council, which noted that “specific rules have been also agreed for foundation models, large systems capable to competently perform a wide range of distinctive tasks, such as generating video, text, images, conversing in lateral language, computing, or generating computer code.” In particular, the provisional agreement provides that “foundation models must comply with specific transparency obligations before they are placed in the market.” The companies behind such GPAI models will need to provide “technical documentation, comply with EU copyright law and disseminate detailed summaries about the content used for training,” among other things.

Meanwhile, a “stricter regime” was introduced for high risk/impact foundation models – or those “trained with large amount of data and with advanced complexity, capabilities, and performance well above the average, which can disseminate systemic risks along the value chain.” For models in this realm, companies will need to “conduct model evaluations, assess and mitigate systemic risks, conduct adversarial testing, report to the European Commission on serious incidents, ensure cybersecurity, and report on their energy efficiency.”

Exceptions for law enforcement: Several changes to the Commission proposal were agreed relating to the use of AI systems for law enforcement purposes. “Subject to appropriate safeguards, these changes are meant to reflect the need to respect the confidentiality of sensitive operational data in relation to their activities,” according to the Council. For example, an emergency procedure was introduced allowing law enforcement agencies to deploy a high-risk AI tool that has not passed the conformity assessment procedure in case of urgency.”

Moreover, with regards to the use of real-time remote biometric identification systems in publicly accessible spaces, “the provisional agreement clarifies the objectives where such use is strictly necessary for law enforcement purposes and for which law enforcement authorities should therefore be exceptionally allowed to use such systems.” The provision agreement provides for “additional safeguards and limits these exceptions to cases of victims of certain crimes, prevention of genuine, present, or foreseeable threats, such as terrorist attacks, and searches for people suspected of the most serious crimes.”

Penalties for non-compliance: The fines for violations of the AI act were set as a percentage of the offending company’s global annual turnover in the previous financial year or a predetermined amount, whichever is higher. This would be €35 million or 7 percent for violations of the banned AI applications, €15 million or 3 percent for violations of the AI act’s obligations and €7.5 million or 1.5 percent for the supply of incorrect information.

The provisional agreement provides for what the Council calls “more proportionate caps” on administrative fines for SMEs and start-ups in case of infringements of the provisions of the AI act.

The agreement also makes clear that a natural or legal person may make a complaint to the relevant market surveillance authorityconcerning non-compliance with the AI act and may expect that such a complaint will be handled in line with the dedicated procedures of that authority.

Enactment & next steps: While the provisional agreement provides that the AI act should apply two years after its entry into force, with some exceptions for specific provisions, the agreement is still subject to formal approval by the European Parliament and the Council and will entry into force 20 days after publication in the Official Journal. The AI Act would then become applicable two years after its entry into force, except for some specific provisions: Prohibitions will already apply after 6 months while the rules on General Purpose AI will apply after 12 months.

THE BIGGER PICTURE: The AI is the not the first national/bloc-wide rule to regulate AI; this summer, China rolled out what the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace called “some of the world’s earliest and most detailed regulations governing AI.” Even still, the AI Act is significant, as it is sweeping in scope and may set a blueprint for other countries. Critics have primarily pointed to the speed with which the Council is adopting new rules, arguing that more time is necessary to determine the specific aspects in need of regulation before enacting legislation. Others have pointed to exceptions for law enforcement, opt-outs for developers, and the potential impact on the EU economy, among other things, as problematic.

On the other hand, the provisional agreement is also receiving praise as giving players in the AI space a framework for the assessment and mitigation of risk, providing protection for consumers amid the striking rise of AI technology, and balancing the need to technological innovation against the tenets of safety and fairness.