Marc Jacobs and Nirvana made headlines late last year when a corporate entity of the world-famous band filed a strongly-worded lawsuit against the New York-based brand for allegedly “infringing Nirvana’s copyright [and] misleadingly using Nirvana’s trademarks” in its iconic x-eyed, squiggly-mouthed smiley face graphic, “and utilizing other elements with which Nirvana is widely associated to make it appear that Nirvana has endorsed or is otherwise associated with” Marc Jacobs’ “Bootleg Redux Grunge” collection.

That case is currently underway before a federal court in California, and while certainly noteworthy in its own way, the case is not entirely unique. In fact, property fights over the ubiquitous, universal symbol for happiness are nothing new. Companies other than Nirvana have brought frown-inducing lawsuits claiming exclusive rights in smiley face designs, and companies other than Marc Jacobs have found themselves on the receiving end of such litigation for their use of various smiley-centric iconography.

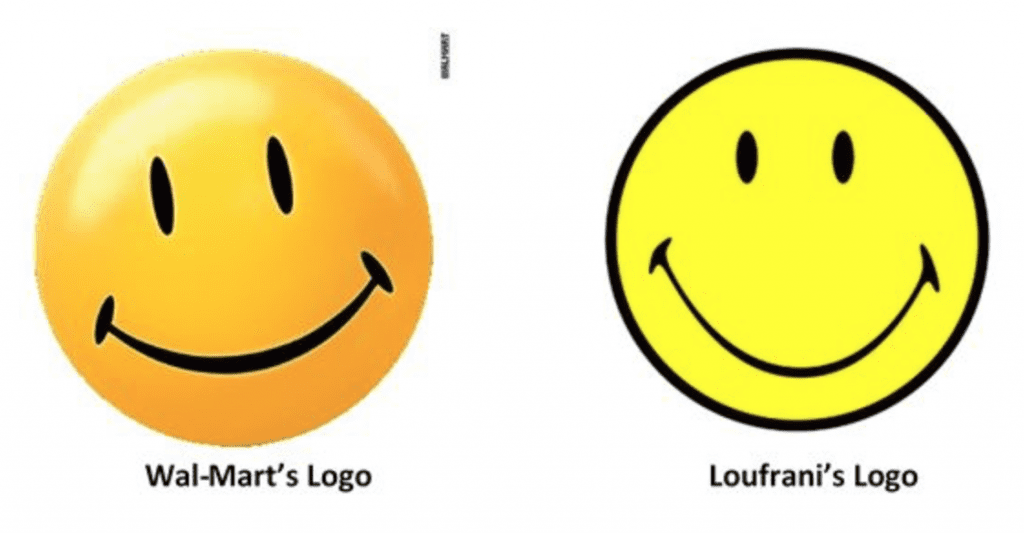

Wal-Mart, for instance, has used a minimalist, yellow smiley face logo for decades to alert shoppers to deals. That smile – which Walmart had used since 1990 – faded to a frown in 2001 when the American retail behemoth discovered that multi-national licensing company The Smiley Company was earning millions by leveraging its rights in a similar yellow smiley face around the world. (The Smiley Co.’s simple-but-lucrative little symbol dates back to 1971, when CEO Nicolas Loufrani’s father, Franklin Loufrani – a former journalist who was working as a business consultant for Paris-based publication France-Soir at the time – drew the circular smiley graphic in the wake of the 1968 student riots in France).

After Franklin Loufrani filed a U.S. trademark application to secure the exclusive right to its smiley face logo in the United States, Wal-Mart took action by commencing an opposition proceeding before the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“TTAB”) of the United States Patent and Trademark Office. In its opposition filing, Wal-Mart alleged that Loufrani’s smiley face was not distinctive enough to function as a trademark, and even if it was, Wal-Mart had prior and superior rights in its own smiley face design. Wal-Mart also alleged that Loufrani’s logo was likely to cause consumer confusion with its logo.

The opposition proceedings between Walmart and The Smiley Company went on for nine long years until the TTAB issued a decision in Wal-Mart’s favor. The TTAB held that while neither of the parties’ respective smiley face logos were inherently distinctive, Wal-Mart’s logo had acquired distinctiveness in the United States, whereas London-based Loufrani’s had not. The TTAB also held that Loufrani’s logo was likely to cause confusion with Wal-Mart’s logo.

Undeterred, in 2009, Loufrani filed a lawsuit in Illinois federal court, alleging that his smiley face logo was “readily distinguishable” from Wal-Mart’s. The parties eventually settled their dispute in 2011, and both parties continue to use their respective logos.

Since then, the fights over happy faces have continued. In 2015, Pennsylvania-based restaurant chain Eat n’ Park – which holds a trademark registrationfor a smiley face logo in connection with cookies – sued Chicago American Sweet and Snack for using a smiley face on its cookies. To many social media users, the dispute appeared absolutely ridiculous. Based on court documents, the parties appear to have settled their dispute before that ridicule could continue for too long.

Ownership Rights in the Smiley Face Design

While companies like Nirvana, Wal-Mart, and Eat n’ Park might claim rights to the depiction of a smiley face, many believe that the original yellow smiley face was first created over 50 years ago in Worcester, Massachusetts by graphic artist Harvey Ball. As the story goes, Ball conceived of the design in 1963 when he was asked to create an iconic graphic to raise the morale of insurance company employees after a series of corporate mergers. Ball apparently completed the design in less than 10 minutes and received $45 in cash for his work.

The State Mutual Life Assurance Company (now known as Hanover Insurance) created tons of buttons bearing Ball’s iconic design as a way to get its employees to smile more. While we do not know if Ball’s design actually worked to boost employee morale, the smiling face became an iconic image.

Although neither Ball nor State Mutual appear to have tried to register the design as a trademark or assert their copyright over others, they may have the strongest historic claim to this iconic symbol.

Natasha Reed is a partner in Foley Hoag’s Intellectual Property practice, resident in the firm’s New York office. Her practice covers all aspects of trademark and copyright law with an emphasis on global protection for multinational businesses. (Intro courtesy of TFL.)