Luxury watches are coming to the metaverse. Sportswear brands like Nike and adidas, and fashion companies, such as Gucci, Versace, and Ralph Lauren are not the only ones eyeing the burgeoning combination of the “real” and virtual worlds, and filing trademark applications for registration for uses of their marks in the so-called “metaverse” in the process. Luxury watchmakers appear to be increasingly considering their role in the virtual world, and in a growing number of instances, they are filing trademark applications with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) and other national trademark bodies to register their names and logos – and even more interestingly, their famed watch faces – in virtual form.

One of the most recent efforts on this front comes by way of Audemars Piguet, which filed a trademark application for registration for a mark that consists of the “configuration of a watch face together with a bezel having a circular inner shape and an octagonal outer shape with slightly rounded sides together with eight visible screws placed in the angles of the octagonal shape and forming an outer ring around the glass of the watch face.” The mark at the heart of the intent-to-use application – which was filed with the USPTO on February 23 and cites impending uses in Classes 9 (downloadable virtual goods), 35 (retail store services featuring virtual goods), and 41 (entertainment services, namely, providing on-line, non-downloadable virtual goods) – is a nod to the design of the Swiss watchmaker’s Royal Oak.

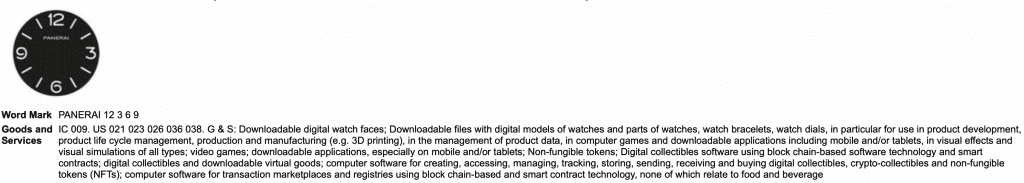

Not the only pending trademark application for registration of its kind, Panerai filed a Class 9 application with the USPTO in January for a mark that consists of a “circular watch face design” with a dial that features “oversized stylized numerals ‘12’, ‘3’, ‘6’, and ‘9’ and markers at the remaining hour positions,” and the “stylized wording ‘PANERAI’ [that] appears below the ‘12’ o’clock position.”

Meanwhile, Bulgari filed an application with the European Union Intellectual Property Office in January for a mark that extends to elements of the face of its Octo Finissimo watch for use in Classes 9, 14 (namely, “watches and jewelry incorporating digital codes, labels, tags and chips linked to a non-fungible token”), and 35.

Secondary Meaning in the Metaverse

Efforts by watchmakers to protect the source-identifying configurations of their famous products is not new. Brands ranging from Panerai to Patek Philippe maintain trademark rights in – and in no small number of cases, registrations for – elements of their timepieces for use on physical watches, watch parts, and corresponding retail services. And in much the same way as they have had to establish that their product designs have acquired distinctiveness in order for those marks to be registered by the USPTO – by showing that that “in the minds of the public, the primary significance of [the mark] is to identify the source of the product rather than the product itself,” the pending trademark applications for their marks in the metaverse will undoubtedly call for showings of secondary meaning, as well.

(When it comes establishing secondary meaning for configurations of physical goods, companies usually point to five years of exclusive use in addition to an array of factors, such as advertising expenditures, sales, unsolicited media coverage, etc. These elements may or may not be helpful for brands seeking to register their marks for use in the metaverse due to brands’ limited activities in this burgeoning space to date.)

The notion of secondary meaning in the metaverse (which we previously touched on here) will certainly raise some interesting – and potentially novel – issues, including how you evaluate or prove secondary meaning for products in the virtual world.

“The typical strategy of pointing to five years of use of the mark in commerce in connection with the goods would seem not to apply here,” trademark attorney and former USPTO Examining Attorney Ed Timberlake tells TFL, given that few brands have been operating consistently in the virtual goods space for that amount of time. And while the USPTO is free to accept other evidence to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness, it is too soon to tell what brands are likely to submit – and what the USPTO will find persuasive. As of now, the USPTO has not reviewed many – or any – trademark applications for registration for virtual product configurations; Audemars Piguet’s February 23 application may be the first on this front, and thus, could provide a blue print for future filing parties.

“Under the circumstances,” Timberlake says that “evidence of prior trademark registrations might be the most appealing strategy,” which then, of course, poses the question of whether a company’s tangible goods from prior registrations would be considered “sufficiently similar to the virtual goods identified in the pending application(s) for registration for the purpose of establishing that distinctiveness as to source has been acquired.”

Watches in the Metaverse

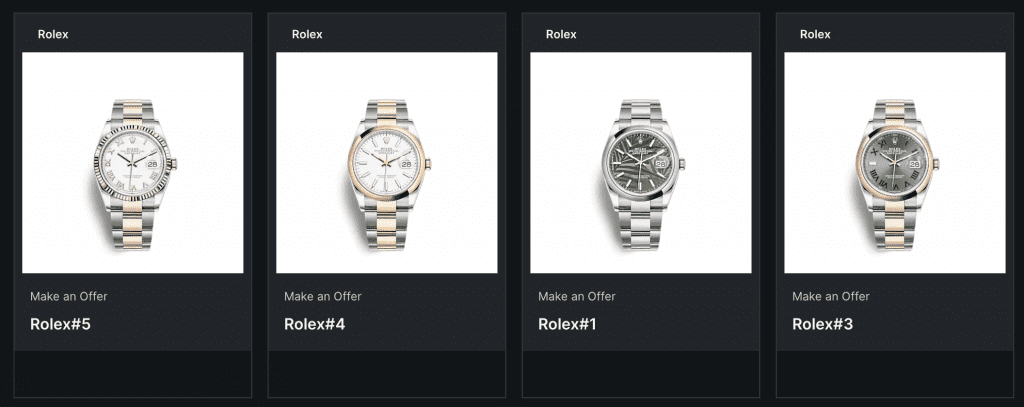

The impetus behind brands’ attempts to seek out virtual goods registrations are numerous, with one, of course, being plans to participate in the virtual world in some capacity – if for no other reason than to potentially build up more robust rights to fend off the inevitable infringement. Non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) tied to images of Rolex watches, for example, have populated marketplaces like OpenSea and LooksRare. The same goes for Audemar Piguet, Patek Philippe, Paneria, Bulgari, etc. Actually operating in the metaverse might give brands more room to claim likelihood of confusion, for instance, in a trademark infringement case.

At the same time, it is worth noting that while many luxury watch brands are not rushing to pop up in any of the existing metaverse platforms, others are making inroads without them. Swiss watchmaker Richard Mille, for instance, is at the center of another party’s NFT venture – albeit in a seemingly unaffiliated capacity. The owner of Bored Ape 6068 – which is known as Richape Mille – recently revealed a collection of NFTs called Metalus. (Note: As distinct from the terms tied to most NFTs, buyers of Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs maintain commercial rights in their apes and thus, can make use of images of their apes in a variety of ways.)

Consisting of “digital reproductions of 100 of the most iconic watches in watchmaking history” – from Patek’s Nautilis to Rolex’s Daytona, the Metalus collection is Richape Mille’s “way of paying homage to an iconic piece of watchmaking history, the Patek Philippe Nautilus,” one of the project’s founders Hannu Siren told Bitcoinist. Before that, Jesus Calderon launched Gen Watches, which exist as “digitally rendered spoofs” on famous watches, Hodkinee reported in January. Among Calderon’s JPG or GIF-centric offerings? Rødex Daitonas and Rødex Bitmariners. The rise in such third-party uses may prompt brands to consider how they can participate in the virtual world if for no other reason than to “own” the space – and exert careful control over the experience – when it comes to their famous marks.

Still yet, in the same way as watchmakers release limited products aimed at deep-pocketed brand devotees (Tiffany & Co.’s latest offering in collaboration with Patek Philippe comes to mind), it is easily conceivable that watchmakers will court collectors, a portion of whom may also happen to be crypto fans, by way of limited-edition NFT-tied offerings.

But beyond purely creative uses of their famed products in the so-called metaverse, the likely outcome (and the arguably stronger use case) for hard luxury brands in the virtual world will probably consist of a combination of creative products, and uses born from a utility perspective, hence, the reference to NFTs in many of watchmaking brands’ trademark applications.

Speaking about the potential for use of NFTs in connection with Tag Heuer products, CEO Frédéric Arnault recently said that owner LVMH “believes that blockchain can transform” luxury brands’ operations by “giving digital ownership” to consumers, among other things. Arnault’s father, LVMH chairman Bernard Arnault has vocally opposed to notion of selling entry-level virtual products, Frédéric states that the group sees potential in terms of “track[ing] products in the supply chain and then afterwards, selling those products with a digital twin,” which could come in the form of an NFT.

Bulgari and Hublot are currently making use of LVMH’s Aura blockchain technology, and as of last spring, Tiffany & Co. was said to be the next “obvious” brand to give it a go. And all the while, other watchmakers, such as Kering-owned Ulysse Nardin and Richemont’s Vacheron Constantin, have been deploying blockchain certification across their collections of timepieces for several years.

A Road Map

As for an example that could prove to be a blueprint for others going forward: Panerai’s very recent “entry into Web3.” In partnership with blockchain technology provider Arianee, the Swiss watchmaker revealed the Radiomir Eilean Experience Edition, a limited-edition watch available in only 50 pieces that is tied to NFT tech. “Each purchaser will receive from Panerai one of the 50 Panerai Genesis NFTs associated with Radiomir Eilean watch in a unique cryptographic wallet allowing them to truly own this non fungible token,” Richemont-owned Panerai revealed on Wednesday.

“The digital asset will unlock exclusive content directly related to the Panerai Experience Edition watches, and will evolve as the experience unfolds to reveal the art piece,” per Panerai, and will give owners “priority access to all future web3 initiatives from Panerai and will be invited to enjoy exclusive services, events and offerings from the brand.”

In a nod to how it will use navigate web3 and NFTs going forward, Panerai says that its inaugural offering “represents the beginning of a deepening engagement,” and that “in time, every Panerai watch will be issued a Digital Passport, as a service to protect its valuable, singular identity, maintain an open line of communication with the brand and unlock benefits and services.”

Chances are, similarly-situated brands will follow suit.