Axel Dumas, the Executive Chairman of Hermès, told shareholders this week that management for the stalwart luxury brand is “curious about and interested in” the metaverse as a potential communication tool. The metaverse-focused commentary comes amid the trademark battle that the Birkin bag-maker has waged against Mason Rothschild, the creator of a collection of MetaBirkins non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”), for allegedly running afoul of Hermès’ rights in the Birkin name and trade dress-protected design. Hermès lodged its trademark infringement and dilution and cybersquatting case against Rothschild in a New York federal court in January, arguing that Rothschild has leveraged the fame of its name and Birkin bags to offer up and sell his NFTs as something akin to luxury commodities.

In one of the latest developments in the case, counsel for Rothschild, which is looking to get the case tossed out of court, doubled-down on its claims in an April 18 letter to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, arguing that Hermès cannot escape the precedent set by Rogers v. Grimaldi. (Under the Rogers test, expressive use of a trademark can be protected by the First Amendment and shielded from trademark infringement liability “unless the use of the mark has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever” and “unless it explicitly misleads as to the source or the content of the work.”) (In that filing, counsel for Rothschild primarily argues that the court should stay discovery until his motion to dismiss is decided.)

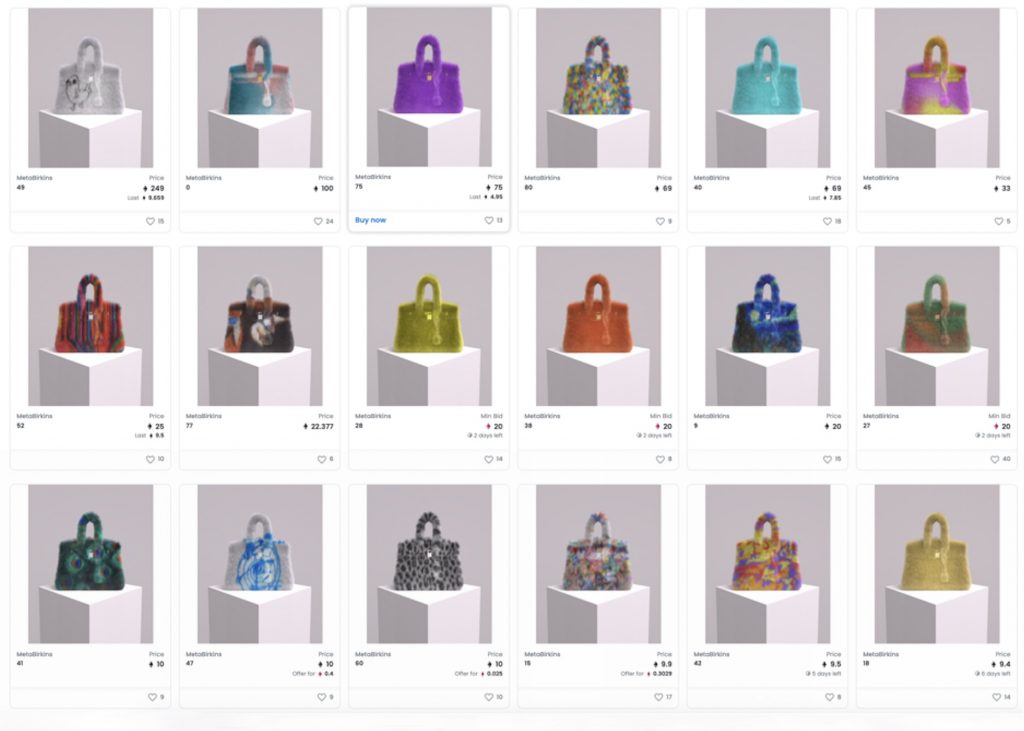

Hermès attempts to “exile [the] MetaBirkins from the world of art (and, consequently, from First Amendment protection)” by “characteriz[ing] the MetaBirkins as ‘virtual handbags’ or ‘digital knock-offs,’ or digital versions, of physical BIRKIN handbags,” according to Rothschild’s counsel. In that same vein, the luxury goods purveyor argues that Rothschild created and offered up those virtual bags – or “commodities” – as an “analog to [its] physical handbags (and at similar prices!),” all while “trading off the substantial goodwill” held by Hermès.

However, Rothschild argues that Hermès falls short, as it “cannot help but admit that MetaBirkins are in fact static digital images, not actual handbags in any sense,” and as a result, the court should reject Hermès’ “assertion that MetaBirkins are somehow outside the First Amendment’s concern.”

The distinction between virtual handbags or commodities, which is how Hermes describes the MetaBirkins NFTs, and art, which is what Rothschild says they are, is critical, as “to escape defeat by Rogers v. Grimaldi, and its progeny,” Hermès has to “plausibly allege that the MetaBirkins are something other than art.” This is precisely why the bulk of the arguments from both sides have centered on what – exactly – is at issue here and how the court should construe the nature of the MetaBirkins NFTs.

This case – and the critical issue of whether the MetaBirkins are, in fact, art that is subject to First Amendment protections – will ideally provide guidance for others in the space by potentially shedding light on how art and fashion can both exist in the so-called “metaverse.”

At the same time, the recently-initiated Nike v. StockX case raises questions about the purpose and value of NFTs. In that case, Nike claims that StockX is on the hook for trademark infringement and dilution, as well as unfair competition, for offering up NFTs tied to images and physical versions of Nike footwear – albeit without Nike’s participation or authorization. The sneaker and apparel marketplace has argued fair use in response, claiming that its Vault NFTs “are absolutely not ‘virtual products’ or digital sneakers,” and rather, each of the NFTs is “tied to a specific physical good that has already been authenticated by StockX.” As such, the NFTs, themselves, have “no intrinsic value,” and essentially serve as a “claim ticket, or a ‘key’ to access ownership of the underlying stored item,” placing them within the realm of the first sale doctrine and nominative fair use. (Rothshild has made similar claims, arguing that the NFTs, themselves, are merely “the technological means by which [he] authenticates his artworks.”)

Both cases demonstrate that “applying even well-settled trademark concepts to NFTs requires a determination of what the NFT represents; is it a physical good, a digital good, a mere certificate of ownership?,” according to Winston & Strawn LLP’s Laura Franco and Dhruva Krishna. And these questions are “just the tip of the iceberg,” they state, noting that “as NFT technology develops and their use expands to non-commercial products, the application of traditional trademark principles to this new technology will only become more complex.”

For instance, Franco and Krishna point to the use of NFTs as governance tokens for Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (“DAOs”) – which are member-owned communities without centralized leadership that are organized and governed by smart contracts on a blockchain network – as bringing to the table “layered uses” of NFTs that beyond mere representation of physical and digital products. For DAOs, they contend that “NFTs not only represent an underlying image or a practical function, but also convey valuable governance” – and ownership – “rights,” representing each person’s stake in the DAO and potentially enabling purchasers to vote on things like “how the organization is run, how assets are allocated, how to vest authority, [and] how the tokens are used.”

As the use of NFTs continues to evolve, “Trademark owners be forced to answer the question of what the NFT represents, but they will also have to answer the question of who it can sue, and whether a remedy in the form of an injunction is even possible,” per Franco and Krishna. And “as NFTs fulfill increasingly diverse purposes, the complexity of issues trademark owners will face to protect their brands is destined to grow in lockstep.”