It is almost impossible to discuss the style of pop mega-star Billie Eilish without the word “bootleg” coming up. There was the headline-making Louis Vuitton-esque toile monogram-printed denim look that she wore on stage at the Coachella Music Festival last spring, and the rainbow-bright “LV” printed outfit she chose for the Los Angeles launch party for her Grammy Award-winning album, “When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go?,” before that. Remember the chocolatey-brown interlocking “G” logoed hoodie-and-shorts combo she wore to perform on Jimmy Fallon in 2018? Or how about the roomy cargo shirt-and-shorts emblazoned with Chanel’s double “C” logo that she appeared in for her Camp Flog Gnaw performance that same year?

In each of those instances, the legally-protected logos (i.e., trademarks) of Louis Vuitton, Gucci, and/or Chanel were emblazoned upon the materials used to make the garments. Yet, none of those outfits were the products of the brands, themselves. The same goes for the marigold-hued shorts-and-jacket set that 18-year old Eilish wore at an event promoting her album this spring. While the textiles for that look were authentic (and crafted from authentic Louis Vuitton towels), the look, itself, was – again – not a creation of the Paris-based luxury goods brand. This same set of facts also holds true for the magenta string bikini that fellow musician Lizzo wears in a recent Rolling Stone spread. The bathing suit was made from real Louis Vuitton materials, but the modified version was not created – or authorized – by the brand.

These instances – which very well might give rise to trademark infringement, dilution, and/or counterfeiting claims for the brands – are hardly isolated ones. They are part of a larger movement being heralded by “bootleg” creators, such as Imran Moosvi, Chanel Copy, Vandy the Pink, and Etai Drori, who have found fans in some of the biggest names in music and pop culture years after Harlem-based tailor Dapper Dan famously put this phenomenon in motion in the 1970s when he first began offering up designer bootlegs from his atelier at 43 East 125th Street in New York City.

There is something more striking at play than the rise of this new breed of “knockoff artists,” as they are often called, and their logo-laden wares: the fact that they have been able to thrive. In other words, as of now, court dockets in the U.S. are not being saturated by lawsuits filed by the brands whose logos have been co-opted – without their authorization – for these popular wares.

Interestingly, the fact that brands have not (yet) called foul by way of litigation is not necessarily because they lack the basis to do so. In fact, potential legal grounds abound. For example, when the textiles at issue are outright fake, such as the ones used by Moosvi, counterfeiting claims are available to the trademark rights holders, which Dapper Dan learned when he found himself on the wrong side of the now-LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton-owned Fendi and the law in the 80s. (At the time, Fendi did not fall under LVMH’s ownership umbrella).

As for the garments created from authentic materials and reconstructed into different products, brands still might have claims. Trademark infringement could be one viable cause of action, given the risk of confusion that comes with this specific breed of high-end bootlegs.

The risk that consumers might be confused as to the source of the bootleg products, themselves (in a post-sale capacity), and/or the brands’ involvement in the making of those products – which is the central element in a trademark infringement inquiry – is particularly relevant in light of the adoption of these wares by celebrities. Such a potential for confusion is heightened due to high fashion’s obsession with streetwear and its penchant for streetwear/skatewear-centric collaborations – from Louis Vuitton and Supreme’s highly-anticipated tie-up in 2017 to Stussy and Dior Homme’s more recent partnership for Pre-Fall 2020. And after years of being on the wrong side of trademark law, Dapper Dan is now actively collaborating with Gucci.

Against this background, it is not outlandish that someone might think that the aforementioned “bootleg” wares are the result of a collaboration with the luxury brand at issue.

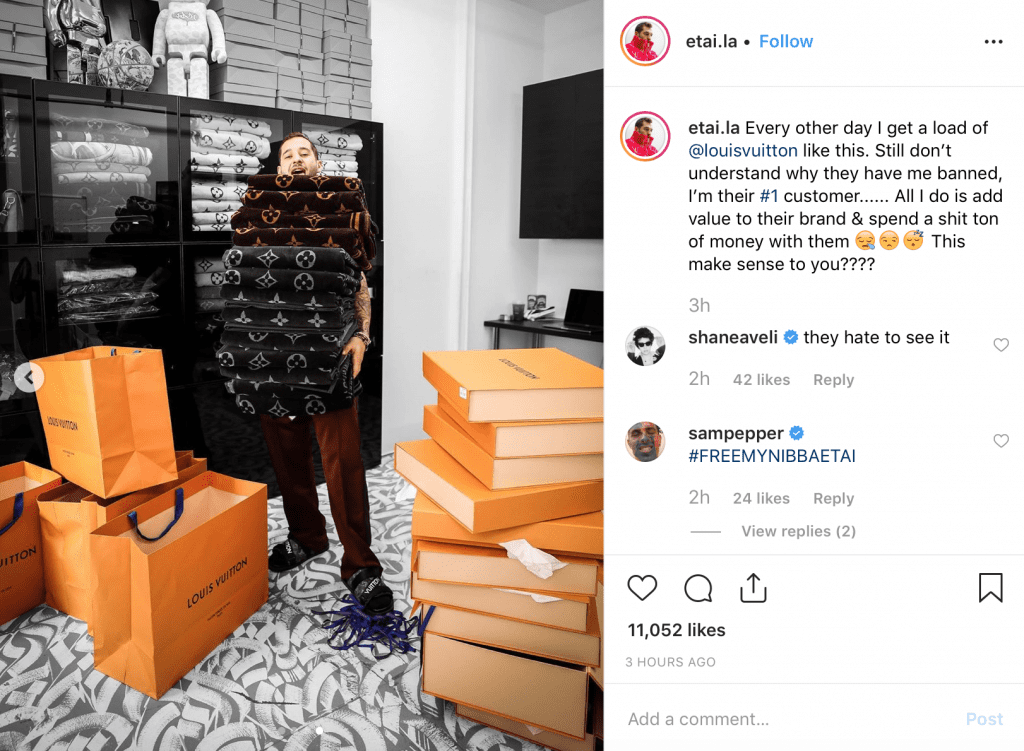

It also bodes well for the brands’ hypothetical cases that their potential infringement claims likely would not be overcome by sale doctrine arguments on the part of the bootlegger. A trademark (and copyright) tenant, the first sale doctrine is a defense to infringement that holds that once a trademark owner, such as Chanel, releases its goods into the market, it cannot prevent the subsequent re-sale of those goods by their purchasers. This rule assumes, of course, that the physical condition of the goods in question has not been altered or impaired. That latter bit is the kicker for bootleggers, as the subsequent use (i.e., the Etai Drori-designed garments, for example) is “materially different” from the initial one (i.e., the Louis Vuitton towels or blankets that Drori purchased and crafted into clothing), a distinction that would likely stomp out any first sale protections.

With the foregoing in mind, the fact that brands have not taken public-facing legal action (as of now) likely does not mean they are without the ability to do so. It also does not mean that they are not potentially dealing with these issues in an out-of-court capacity.

There are suggestions that this very well may be the route that brands are taking. For example, the Instagram account of Tsuwoop, one of Eilish’s go-to creators, used to be filled with Louis Vuitton logo-covered wares – from Toile Monogram-printed hoodies and sweatsuits to multicolore-covered board shorts and bucket hats. Those posts have all disappeared, which might suggest that the brand objected, albeit without filing suit. Meanwhile, Drori alleged in an Instagram post in September 2019 that Louis Vuitton “banned” him from making purchases, presumably to cut down on his pattern of churning out logo-emblazoned wares of his own.

The potential for quiet efforts falls neatly in line with the sentiment that Louis Vuitton CEO Michael Burke shared with the Wall Street Journal back in May 2019. Speaking of the “bootleg” creations that have found their way onto some of the buzziest names in music, Burke revealed that he does not think that lawsuits “are a good solution.”

To some extant, Burke’s approach stands in stark contrast to many major luxury brands’ traditional practice of aggressively policing unauthorized uses of their trademarks in order to avoid consumer confusion, genericization of their marks, and/or dilution, and to ensure that their wildly valuable marks remained in-tact both from a legal perspective and also from a consumer perception one; brand valuation can be impaired by a market saturated with counterfeits or otherwise infringing products.

At the same time, though, he also told the publication that he “doesn’t rule out legal action against” bootleg creators, which very well might mean that if the perfect case comes along, the brand’s mighty legal department could pounce.

After all, that is precisely what Louis Vuitton did when it filed suit against Junkmania, accusing the popular Japan-based online seller of customized footwear and accessories of running afoul of the law by way its “customized” products that incorporate textiles covered in Louis Vuitton’s trademarks. In that case, Louis Vuitton called these wares little more than glaring examples of unfair competition, and the Japan Intellectual Property High Court agreed, siding with the Paris-based brand and its argument that Junkmania was violating the Japan Unfair Competition Prevention Act, which outlaws the use of “another’s famous indication of goods or business … for a purpose of acquiring an illicit gain.”

It will be interesting to see if luxury brands take similar action in the U.S., as while Eilish may have moved on the real thing as indicated by her wardrobe on recent red carpets, some of her favorite bootleggers are still up to their old tricks leaving room for brands to take action if/when the right case comes along.