Three brands reign supreme when it comes to dominance in the soft luxury segment: Hermès, Chanel, and Dior. In a lengthy note on Thursday, Bernstein analyst Luca Solca dove into the three luxury power players, noting that while they occupy “the same space [in the market], these brands come from very diverse backgrounds, which leads to different category mix and relative price positions,” and also different strategies when it comes to growth. Referencing the “soft luxury pyramid,” Solca situates the likes of Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Celine, Balenciaga, Prada, Bottega Veneta, and co. right below these three “high-end mega-brands” – in the “aspirational” tier, and below that, puts the likes of Coach, Ralph Lauren, and Michael Kors, among others, in the “accessible luxury” camp.

Among the key points of interest in the Bernstein note is, of course, the pricing positions – and approaches to price increases – that Hermès, Chanel, and Dior are taking, with Hermès’ iconic handbags, for instance, “traditionally [sitting] at the top of the pricing pyramid,” while Dior has taken the title of “the homegrown Chanel challenger” thanks to the strategy that has been envisioned and implemented in recent years by CEO Pietro Beccari, who succeeded Sidney Toledano in 2017, and creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri, who has been at the helm of the LVMH-owned brand since 2016.

Specifically, Solca states that under the watch of Beccari and Chiuri (and since the brand was fully integrated under the LVMH umbrella in 2017), the “new” Dior – complete with its “pioneering” position when it comes to collaborations, market share gain in the skincare segment, successful adoption of local brand ambassadors, including in China, and high visibility across social media channels – has “resonated with consumers and has been in recent years the hottest brand in the high-end.” This comes “hand in hand with continuing increases in pricing to further establish the brand’s high-end credentials.”

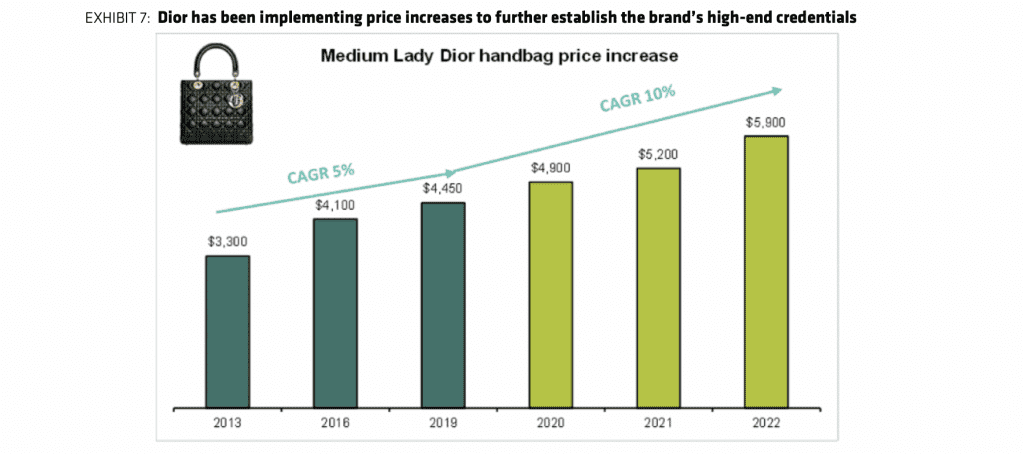

Dior has been implementing prices hikes for its bags, such as the Medium Lady Dior, which is up by almost $1,500 from 2019 (with a compound annual growth rate of 10 percent between then and now). Rising price tags are particularly noticeable in China, where the CAGR for certain models, such as the Medium Lady Dior, amounts to 20 percent between November 2019 and January 2022. Bernstein states that Dior, nonetheless, “offers the highest pricing upside” of the three brands at issue, as the Lady Dior is still sold today at a 30 percent discount to its Chanel counterpart. That gap is likely to slim given that LVMH chairman Bernard Arnault said in an earnings call last week that “reasonable” price increases are on the horizon. (Bernstein estimates that Dior had sales of EUR 9.099 billion ($10.37 billion) for the 2021 fiscal year.)

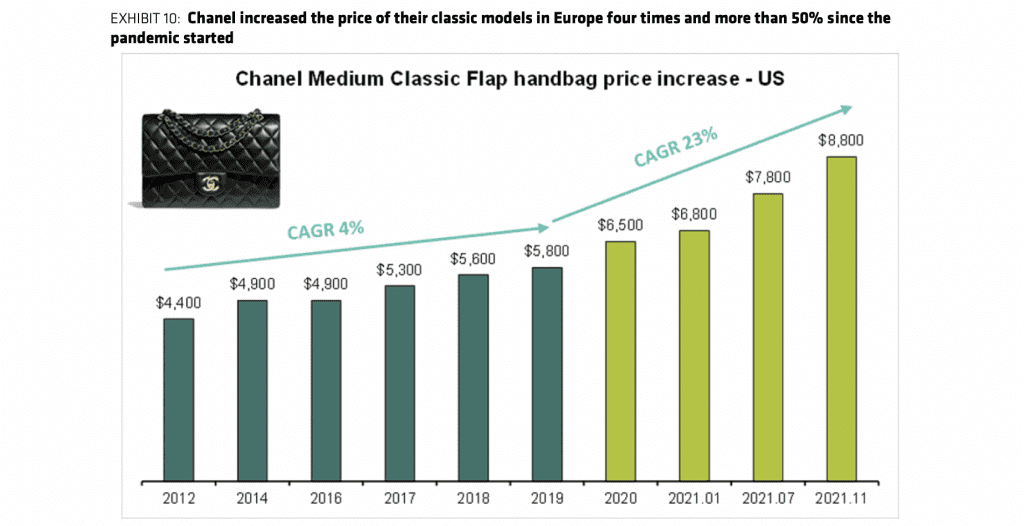

Turning their attention to Chanel, the Bernstein analysts noted that the company increased the pricing of its classic models four times and more than 50 percent since the pandemic started, thereby, “bringing them in line with a Birkin/Kelly 2.” For example, Chanel’s Medium Classic Flap bag increased in price in the U.S. from $6,500 in 2020 to $8,800 as of November 2021, giving it a CAGR of 23 percent. (For some perspective, the CAGR for the same bag was 4 percent from 2012 to 2019.) The growth rate for Chanel bags more broadly, including the Small, Medium, and Large Flap styles, was outsized in China, reaching 32 percent, and despite such high price increases, Berstein states that the Classic Flap bags are still “sold out everywhere in China.”

Moreover, Chanel – which likely generated sales of EUR 14.247 billion ($16.27 billion) in FY21E – adopted a quota system for certain bags, prompting comparisons (including by TFL) to the distribution model that has been in place at Hermès, thereby, limiting the number of certain bags that consumers can purchase within a certain period of time, prompting at least some consumer pushback, namely on the quality front. (Chanel’s president of fashion Bruno Pavlovsky stated in December that Chanel had “not put new limitations on selling in any country,” but simply “had a big successful year, especially in Korea,” and did not “have enough products – especially for handbags.”)

“Secondary market prices have yet to catch up with the primary market shift, with Chanel bags selling on average for 75 percent of their retail value vs. Hermès at 90 percent-plus,” per Bernstein, which “suggests that the latter brand has potential to gain market share from Chanel as consumers still perceive Hermès bags to be more valuable than Chanel bags (despite them selling for very similar retail prices).”

Finally, in terms of Hermès, it has “stuck to its well-established formula,” meaning that prices of the French luxury goods brand’s most iconic bags, namely, its Birkin, have “remained relatively stable in the past ten years,” Solca states. The only major event was “a mild price hike across products in China in 2021, at the risk of suffering from production bottlenecks in the face of outsized consumer demand.” Bernstein says that it expects Hermès’ 2021 sales to amount to EUR 9.069 billion ($10.36 billion).

Looking beyond bags, Solca notes that with their roots in couture, Chanel and Dior “stand at the top of the pricing scale with their apparel,” with Chanel boasting “the most sizable couture business of the industry,” and introducing relatively “new product categories – like watches and jewelry – [which] have been set up with a sharp focus on quality.” Meanwhile, both brands have developed “very material” beauty businesses in order to boost additional growth. As for Hermès, Solca notes that “apparel and even more so beauty are more recent developments,” with the brand first launching its beauty range in 2020, and more traditionally, Hermès has “used silk (e.g. ties and scarves) as the entry point to the brand.”

Reflecting on the three brands together, Solca notes that what they “have done with iconic handbags [in terms of] item scarcity and price increases has pushed their bags to new desirability levels,” which is no small feat in light of the fact that “establishing icons is a most difficult process in the luxury goods industry,” and even once they are established, “icons need to stay relevant to consumers,” whic is “a more subtle process than reinventing the catwalk collection every season, and more similar to what Rolex does with Daytona or Porsche with 911.”