In early 2016, an almost entirely unknown company set its sights on one of the buzziest brands in the world and began laying the foundation for what would quickly become an expansive trademark-collecting scheme, one that stretches from the tiny enclaved microstate of San Marino to the densely-populated Chinese mainland. Since then, that company, a 3-year old British firm called International Brand Firm (“IBF”), has managed to build up an arsenal of trademark registrations in the name and famous box logo of Supreme trademark for use on garments and accessories in a growing list of countries.

Playing on global demand for the 25-year old cult streetwear brand and its markedly unhurried expansion efforts outside of a few U.S. cities and a smattering of international capitals, IBF has essentially co-opted Supreme’s schtick – from its well-known logo to a fair share of its wildly-devoted followers. IBF even beat Supreme to China, where the London-based holding company announced a short-lived collaboration with Samsung and opened up shop in Shanghai.

Aside from identifying an opportunity in Supreme’s tightly-controlled distribution chain (limited quantities sold exclusively in brand-owned and operated stores), and its razor-sharp focus on very-deliberate and measured expansion, IBF’s ability to hijack an entire brand has been enabled, of course, by jurisdictional variations in trademark law across the globe. In accordance with many-a-country’s national trademark law, registrations are awarded to the first party to simply file an application, not the first to actually use the mark in commerce. This system notoriously bodes well for squatters, or those who intentionally file trademark applications for another party’s trademark in a country where the original rights holder does not currently maintain registrations.

In light of the increasing intensity of IBF’s global operations, Supreme’s legal counsel embarked on an international enforcement effort in 2016, leading to the initiation of legal battles against IBF and related entities before the San Marino Civil Court, the Business Specialized Division of the Court of Milan, and the European Union Intellectual Property Office, among other bodies. Many of those matters are still in the midst of the judicial process, and both Supreme and IBF have vowed to fight for their respective abilities to do business.

All the while, something else has been going on. Another crafty play has been advancing behind the scenes, a move that has seen IBF effectively controlling the narrative surrounding its activities, and thereby painting a far prettier picture of the legality and the legitimacy of its efforts than might otherwise meet the untrained eye.

By way of an affiliated-but-carefully masked website – thestreetwearmagazine.com – and a network of unrelated, third-party publications, the latter of which operate by publishing quickly-aggregated news without significant fact-checking or additional research, IBF, with the help of the modern-day race to publish mentality of most websites, appears to have been able to deftly focus the information that is being spread about itself and its business dealings.

The most striking aspect of IBF’s influence over the media coverage of its ongoing battles with Supreme can be seen in the very terminology that is almost-uniformly used. Nearly every mainstream media article devoted to Supreme v. IBF refers to the copycat red sweatshirts, which feature the word “Supreme” in a Futura Heavy Oblique font, and the knockoff accessories bearing Supreme’s box logo, for instance, that IBF and its partners are proffering, by using one specific descriptor: “legal fakes.”

The term – which refers to “a legal copy of a brand, where ‘legal’ indicates that the fake brand is a trademark registered in a country where the original mark has yet to be launched,” according to Italian trademark attorney Silvia Grazioli of Bugnion SpA – is entirely novel. In other words, “legal fakes” has no foundation in trademark law in the U.S. or elsewhere, and you will not find it mentioned in legal textbooks, case law, or scholarship, unless it is in reference to Supreme and IBF.

According to London-headquartered law firm Bird & Bird, “legal fakes” – which suggests, by its very name, that legally, IBF and co. are not necessarily in the wrong – was adopted “by media outlets to describe Supreme Italia.”

Despite a lack of a legal foundation for this term, it has been used extensively and exclusively in connection with the activities of IBF, Trade Direct, and related entities. Such use can – for the most part – be traced back to two websites: an Italian menswear site called nss Magazine, which has devoted significant coverage to the global fight for Supreme, and another called The Streetwear Magazine. In terms of the latter site, which almost exclusively publishes only articles covering about IBF and Supreme, a rep for IBF told TFL that they do “not have enough information” to confirm whether the website is linked to IBF.

However, according to pre-GDPR Whois.com records, the domain is, in fact, registered to an individual named Michele Di Pierro, the very same person who is listed on public records as the director of IBF.

While the exact origin of the this seemingly legitimate – albeit completely makeshift – legal term of art is relatively vague, one thing is perfectly clear. In pushing a “legal fakes” agenda, IBF and its public relations department has essentially been able to dupe just about anyone without an international trademark law background. More than that, it has been able to put an entirely different – and far more complimentary – face on what would otherwise be characterized as counterfeiting and/or trademark and domain name squatting, and treated accordingly by the media and consumers.

And counterfeiting is precisely how Supreme views IBF’s activities. As TFL first reported in December, and Supreme founder James Jebbia has since confirmed in a recent interview, Supreme and its legal counsel consider the use of “legal fakes” to describe IBF’s dealings to be “misleading and technically erroneous.” In the company’s eyes, IBF’s use of the Supreme trademark on garments “is simply illegal in Italy,” as well as in other countries.

“People should know that the idea of legal fakes is a complete farce,” Jebbia told BoF early this month. “It would be sad if a new generation thinks [that IBF’s activities are] actually legit.”

Beyond the very favorable-for-IBF terminology that has dominated the discussion in this sphere to date, the reporting of the legal proceedings – including the various court decisions and the significance of those developments – have been distorted routinely.

As counsel for the notoriously press-shy Supreme told Hypebeast last month (in furtherance of an effort to correct inaccurate reporting about Supreme and IBF on that site, as aggregated from nss Magazine), “Reports from publications like The Streetwear Magazine [that are subsequently] funneled through other publications like nss Magazine” are responsible for widespread “inaccuracies” in regards to the reporting on Supreme and IBF.

For instance, an August 2018 article from nss – which was widely aggregated by a number of popular menswear sites across the web – stated that Supreme had “lost a case” against IBF in Italy. In reality, what transpired was that a regional court ordered that three websites, www.supremeitalia.it, www.supremeitalia.com and brandshopstore.com – which had been subjected to a court-ordered block as a result of litigation initiated by Supreme’s corporate arm Chapter 4 – be released back to IBF. However, what virtually all articles failed to mention was the fact that what remained intact was a court order barring Trade Direct and IBF from manufacturing and selling products bearing Supreme’s trademarks, including on those websites.

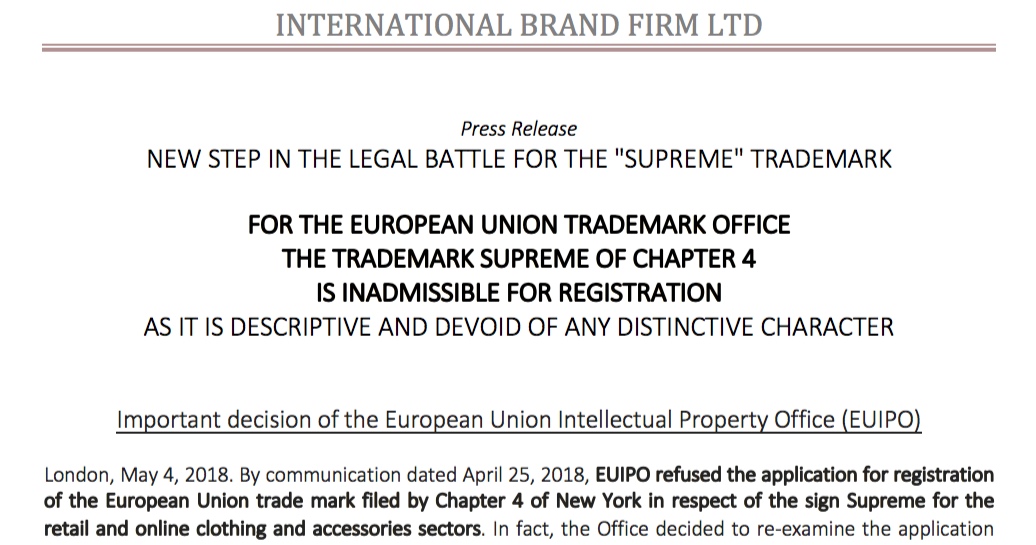

Nonetheless, the development was characterized as a “significant win” for IBF, in much the same way as a preliminary blow to Chapter 4 from the European Union Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”) was. Shortly after the EUIPO released an appeal-able – and thus, non-definitive – decision in April 2018 that one of Supreme’s European Union trademarks was “descriptive, laudatory, and lacking in distinctiveness,” and therefore, potentially not registerable, IBF circulated a press release declaring that “the trademark ‘Supreme’ of Chapter 4 is inadmissible for registration.”

IBF’s press release called the EUIPO’s finding “an important and authoritative statement in the European Union regarding the invalidity of the Supreme sign.” What IBF failed to note in its statement was that Chapter 4 could – and would – fight the EUIPO’s decision, as is thoroughly customary in such trademark proceedings.

In addition to widespread misreporting or overstating of the significance of legal outcomes in the various pending cases, The Streetwear Magazine has been busy publishing regular coverage of the legal fights over Supreme, making sweeping statements that disparage the New York-based Supreme, while helping to bolster the legitimacy of the the Italian and Spanish copycats.

In one article, the unknown author states that Supreme “does not register its own brand,” referring to Supreme’s alleged failure to amass trademark registrations, which is only partially correct, as Supreme’s corporate entity Chapter 4 Corp., does, in fact, maintain an array of registrations.

In another instance, an article contains generalized proclamations, such as “the brand is not really original, but taken from the works of the well-known American artist Barbara Kruger (who did not like the copying and complained openly),” while propping up the workings of Supreme Italia, noting that “SUPREME ITALIA [is] legitimately registered [as a trademark in Italy]” and “since 2015 [Supreme Italia] has made effective and constant use of [its trademark-protected name] in the Italian market through the widespread distribution of [its] products in the best shops” – finding their way into the mix.

As Mr. Jebbia said early this month, more than merely seeing an opportunity to cater to consumers outside of Supreme’s immediate circle of consumers, IBF has “taken full advantage” of the fact that Supreme is well-known to shy from traditional media endeavors. “We haven’t had the time,” he said, “to basically go on this massive disinformation tirade or press thing that most people would.”

Unfortunately for Supreme, however, the ongoing barrage of fake news may be the most damaging part at play here. After all, while bad faith trademark filings, such as IBF’s, can – in many cases – be fought in court, reversing the widespread infiltration of misinformation about the nature of IBF’s endeavors, and the phenomenon of legal fakes more generally, will not be such a straightforward task.

IBF maintains, of course, that is has done nothing wrong. The operators of IBF and Trade Direct vehemently oppose any suggestions that they are running afoul of the law. “Supreme Italia does not sell ‘fakes,’” a representative for IBF told nss early last year. “We are carrying out a completely different project from Supreme New York,” a project that they say the market has “authorized” them to do.