The ongoing shift in the state of luxury licensing has taken a new turn, as Estée Lauder looks to buy out the Tom Ford brand and take control over its former licensor in the process. The New York-based cosmetics giant made headlines early last week, confirming that it will acquire the American fashion brand – which it has held a fragrance/beauty license for since 2006 – for $2.8 billion by way of a combination of cash, debt and $300 million in deferred payments. The headline-making transaction has taken the title of the biggest deal of the year in the luxury segment.

Estée Lauder’s impending acquisition of the Tom Ford brand comes amid enduring changes in how companies approach the well-established practice of licensing. Over the years, luxury names, having built their businesses on leather goods and apparel, have relied on the likes of Coty, L’Oreal, Estée Lauder, and Puig, among others, to produce trademark-bearing fragrance and beauty collections, and/or to Marcolin, Marchon, Safilo, EssilorLuxottica, etc. in order to offer up logo-bearing eyewear. These endeavors – which see companies trade the exclusive right to use their trademarks in certain categories of goods/services in exchange for a lump sum payment and/or royalties based on revenue (or a combination of the two) – enable luxury brands to expand their operations and revenues by way of new product categories and geographic markets with greater ease than if they were to do so in-house.

However, this time-tested pattern of fashion/luxury brands outsourcing certain divisions has not stopped big-name groups from going against the grain and bringing previously-licensed categories in house – or at least, closer to home (via joint ventures). Gucci’s parent company Kering, for instance, announced back in 2014 that it would create an in-house eyewear division in order to tighten control over the business (and the revenues generated) and would gradually walk back on all of it licenses with third parties, such as Safilo. (Kering’s Eyewear division, which manufactures eyewear for Kering’s own brands and has been the licensee of Richemont-owned Cartier’s eyewear since 2017, contributed 706 million euros in revenue to the group in 2021.)

Kering has also been the topic of enduring discussion in connection with reports that it is plotting to bring at least some of beauty licenses in-house, as well, a move that would enable it to better compete with the likes of Chanel and Dior, for example, which run their own fragrance/beauty divisions in lieu of licensing. “Today, the jewels in Kering’s crown are Gucci, whose beauty license is held by Coty Inc., and Yves Saint Laurent, [which is] still with L’Oréal,” WWD reported this summer.

Not to be outdone, luxury’s biggest player LVMH formed a joint venture with eyewear maker Marcolin in 2017 in order to have a stronger hand over its eyewear offerings, and last year, revealed that it would buy out Marcolin’s 49 percent stake in the venture in charge of manufacturing eyewear for brands like Dior, Fendi, and Celine, thereby, giving it complete control over the business.

These moves come as part of a larger push by luxury groups to shore up their supply chains (likely driven, at least in part, by the onset and impact of COVID-centric disruptions) and to exert greater control over the manufacturing and distribution of goods bearing their brands’ names.

A Larger Shift in the Luxury Segment

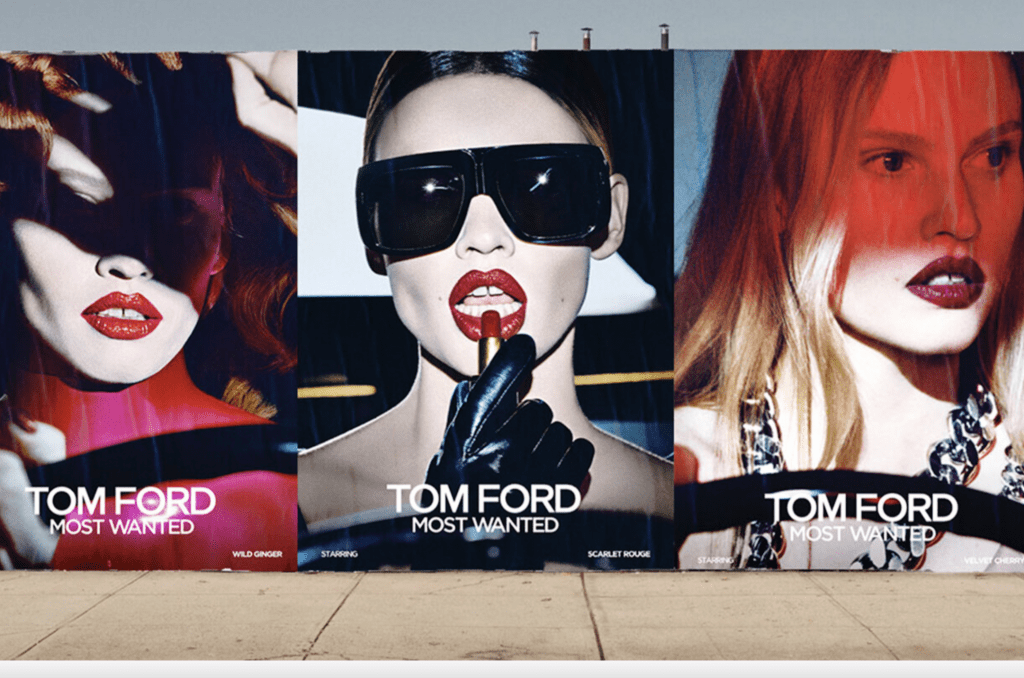

The Estée Lauder, Tom Ford deal is something of a shift in another direction altogether, with the former licensee now becoming the owner and licensor. As Estée Lauder noted in a deal-related release last week that since it first acquired the Tom Ford Beauty license 16 years ago, the venue has “grown into one of the most successful and aspirational beauty brands in the world,” consisting of a “highly differentiated collection of fragrance, makeup, and skin care that reflects Tom Ford’s singular vision of modern glamour, crafted with ultimate quality.”

The deal does not, of course, mark a total shift away from licensing, as Estée Lauder will maintain Ford’s existing deal with eye-manufacturer Marcolin, and in fact, will expand the company’s long-running menswear licensing arrangement with Zegna, which will now produce and distribute both Tom Ford menswear, as well as womenswear, accessories, jewelry, children’s wear and home wares.” (And others in the luxury space are still readily relying on licensing, as well, with Brunello Cucinelli and EssilorLuxottica announcing on Tuesday that they have entered into a 10-year licensing deal for the design, production and distribution of branded eyewear collections.)

In addition to serving as a further nod to the fact that the luxury licensing ecosystem is still evolving, the Tom Ford deal seems to speak to the sheer value of these licensing tie-ups, which can generate revenue that exceeds that of entire fashion brands. UBS estimated that Tom Ford generated almost $1.5 billion in sales in 2021, no small portion of which was driven by beauty/fragrance sales. In its FY 2022 report (for the fiscal year that ended on June 30, 2022), Estée Lauder stated that it expects that the Tom Ford Beauty brand will achieve annual net sales of $1 billion “over the next couple of years.”

“As an owned brand, this strategic acquisition will unlock new opportunities and fortify our growth plans for Tom Ford Beauty,” Estée Lauder said last week. “It will also further help to propel our momentum in the promising category of luxury beauty for the long term, while reaffirming our commitment to being the leading pure player in global prestige beauty.”

THE BOTTOM LINE: The exact model of trademark licensing has been in flux in the luxury segment over the past decade or so, particularly as large luxury goods look to gain greater control over the manufacturing and distribution of their offerings. Licensee-turned-licensor is the latest example of such an ongoing evolution.