Estée Lauder Companies and a handful of its brands have escaped a lawsuit accusing them of violating Illinois’ biometric data lawby way of their virtual try-on tools. Fellow defendant, Perfect, has similarly sidestepped the plaintiffs’ claims, with a judge for the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois granting Estée Lauder Companies, Bobbi Brown Professional Cosmetics, Estée Lauder Inc., Smashbox Beauty Cosmetics, and Too Faced Cosmetics’ (collectively, “ELC”) motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim, and virtual try-on tool technology provider Perfect’s motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction or, alternatively, for failure to state a claim. The closely-watched case is not necessarily over, as the court granted the plaintiffs leave to file a second amended complaint by February 8, 2024.

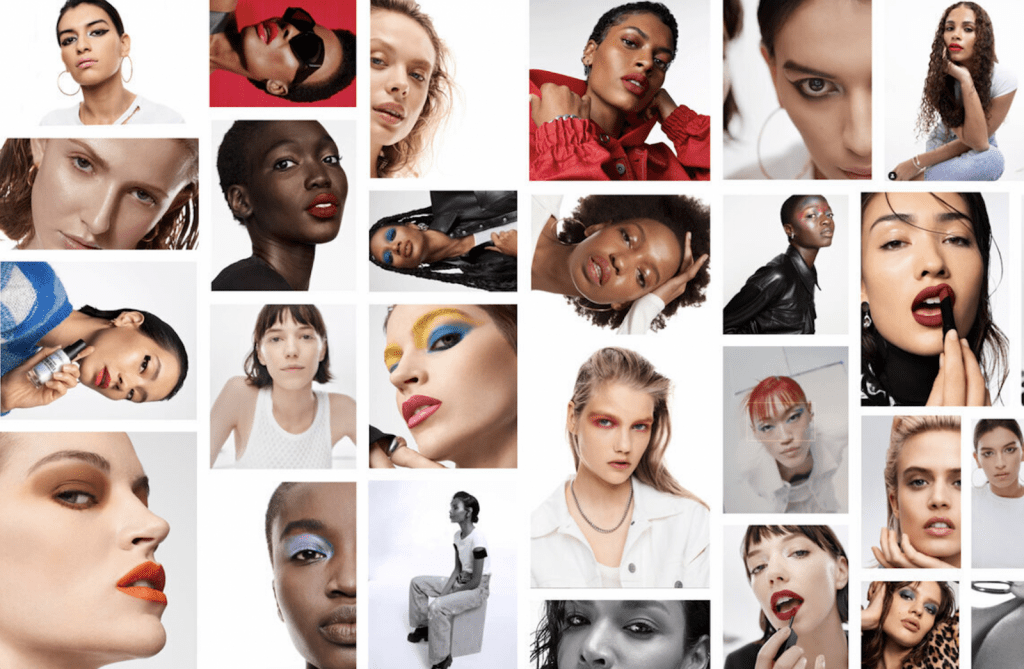

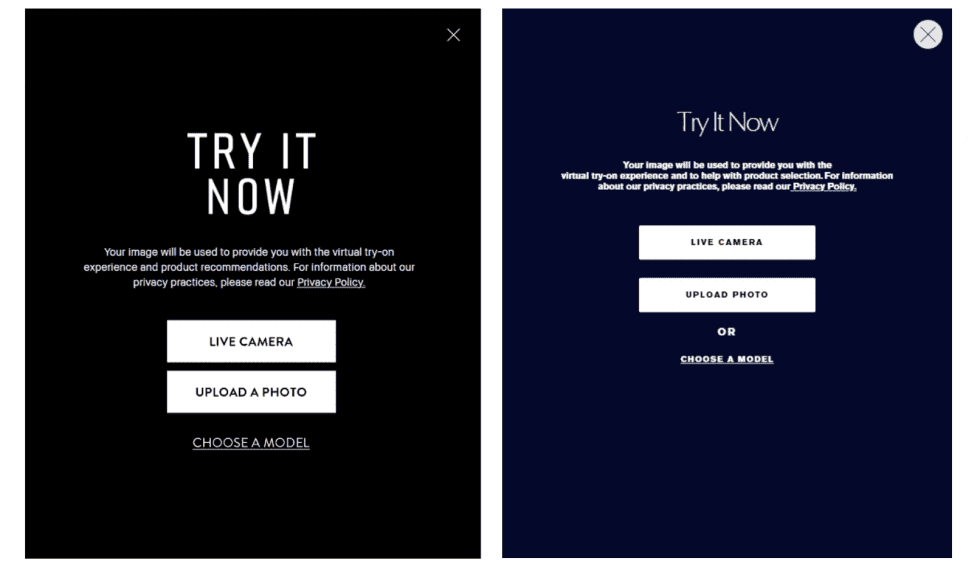

Setting the stage in her order on Wednesday, N.D. Ill. Judge Lindsey Jenkins stated that the case at hand concerns a virtual try-on tool (“VTOT”) that Perfect licenses to ELC that allows consumers visiting the ELC brands’ websites to virtually “try on” cosmetic products using a photo of themselves. The problem, according to Celia Castelaz, Brittanie Nalley, Northa Johnson, and Lori Carter (collectively, the “plaintiffs”), is that when they used ELC’s VTOT “on several occasions in 2021 and 2022,” they were not informed that their biometric data would be captured and used.

Moreover, they alleged that the brand websites’ privacy policies “failed to reference biometric data [or] the VTOT,” ELC did not “require or obtain visitors’ written consent to collect, capture, possess, and/or obtain their biometric data when they used the VTOT on the brand websites,” and the defendants (ELC and Perfect) “failed to craft, publish, comply with, or make publicly available a written policy establishing a retention schedule and guidelines for permanently destroying biometric identifiers or biometric information obtained from brand website users.”

As a result, the plaintiffs argued that ELC and Perfect violated Illinois’ Biometric Information Privacy Act (“BIPA”) by: (1) failing to inform consumers in writing and obtain written release from users prior to capturing, collecting, or storing biometric identifiers; (2) failing to develop and make publicly available a written policy for retention and destruction of biometric identifiers; and (3) running afoul of BIPA’s prohibition against “selling, leasing, trading, or otherwise profiting from a person’s biometric identifiers or biometric information.”

Perfect’s Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Personal Jurisdiction – The court first considered Perfect’s motion to dismiss, noting that the plaintiffs “do not argue that the court has general jurisdiction over Perfect, [and thus,] only specific jurisdiction is at issue here.” The plaintiffs – who need to show, in part, that Perfect “purposefully directed its activities or availed itself to Illinois, and the relationship between Perfect, Illinois, and the litigation arose out of contacts that Perfect created itself with Illinois” – fall short here, according to Judge Jenkins. Among other things, the court found that Perfect’s “unrefuted evidence states that the VTOT is geographically neutral in the U.S. and operates the same for any user who chooses to access and engage with it on ELC’s brand websites, regardless of the state in which the user is located.”

In this case, there is “no indication” that New Taipei City, Taiwan-headquartered Perfect “ever ‘reached into’ or targeted Illinois using the VTOT on ELC’s brand websites,” and instead, the plaintiffs’ claim “hinges solely on the allegation that they visited ELC’s brand websites, where they accessed and engaged with the VTOT; thus, the only connections between Perfect and the forum state are the plaintiffs and ELC,” Judge Jenkins found.

The court also shot down the plaintiffs’ argument that Perfect’s privacy policy establishes personal jurisdiction as the policy and its terms of service provide that Perfect “may collect information about a VTOT user’s location, refers to BIPA,” and states that “it or a third party using VTOT technology may collect biometric information.” According to the plaintiffs, “this shows that Perfect knew and expected to be sued in Illinois and sought the protection of Illinois law in connection with licensing and running the VTOT.” Judge Jenkins was unpersuaded by this argument, noting that she “has not identified any Seventh Circuit case law addressing whether a defendant’s reference to a state’s privacy laws on its website and/or terms of use confers personal jurisdiction over the defendant.”

ELC’s Motion to Dismiss for Failure to State a Claim – In an attempt to escape the plaintiffs’ BIPA claims, ELC argued in its motion to dismiss that the plaintiffs “failed to plead facts that plausibly establish it is capable of using the collected biometric data of brand website users to determine their identities,” and emphasized that the amended complaint does not allege that the plaintiffs provided ELC with “any identifying information, such as names and email addresses (or that they were required to do so in order to use the VTOT), that could connect the VTOT’s facial geometry scans to the plaintiffs’ identities.”

In siding with ELC, the court cited two earlier cases heard by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois …

> Clarke et al. v. Aveda Corp., No. 21-cv-4185 (N.D. Ill. Dec. 1, 2023), in which the court granted Aveda’s motion to dismiss because the complaint contained no plausible allegations that Aveda’s collection of biometric data made Aveda capable of determining their identities.

> Daichendt v. CVS Pharmacy, Inc., 2022 WL 17404488, (N.D. Ill. Dec. 2, 2022) – In reaching its conclusion, the court in Clarke relied on Daichendt, in which the court dismissed the plaintiffs’ BIPA section 15(b) claim because they failed to plead that CVS was capable of identifying them in connection with its collection of their digital passport photos that were scanned for biometric identifiers. Specifically, the court concluded that plaintiffs failed to allege that CVS had collected plaintiffs’ “real-world” personally identifying information, such as names and addresses, which could be connected to the collected scans of their facial geometry.

The plaintiffs in that case subsequently amended their complaint, alleging that CVS had collected their names, email addresses, and phone numbers before scanning their facial geometries, prompting he court to hold that the plaintiffs “plausibly allege[d] that [CVS] collected and stored their personal contact data (‘real-world identifying information’), such as their names and email addresses, which made [CVS] capable of identifying them when associated with scans of their face geometry (‘biometric identifiers’).”

With the foregoing in mind, Judge Jenkins determined that the plaintiffs “fell short of providing any specific factual allegations that ELC is capable of determining [their] … identities by using the collected facial scans, whether alone or in conjunction with other methods or sources of information available to ELC (e.g., the user’s account information such as their name, email, physical address, etc.).” And as such, they “have failed to plead the most foundational aspect of a BIPA claim.”

THE BIGGER PICTURE: The win for ELC and Perfect comes amid a rapid rise in BIPA litigation, which is expected to continue. “While growing BIPA litigation and [a number of] plaintiff-friendly decisions may be cause for concern for many companies,” Ropes & Gray’s Ashley Fisher recently stated in a note, “proposed amendments have leaned in businesses’ favor, and relatively simple steps can bring entities into compliance.”

At the same time, some defendant-friendly decisions have arisen, especially in the fashion/cosmetics context. With this case and a since-dismissed one waged against Dior in mind, there are at least two points worth highlighting for BIPA defendants. An important defense to VTOT-centric BIPA case was demonstrated in the case filed against Dior, with the court finding that Dior successfully argued that its use of a VTOT for eyewear falls under BIPA’s statutory exemption that excludes “information captured from a patient in a health care setting” from its definitions of “biometric identifiers” and “biometric information.” (More about that case here.)

In addition to the “healthcare” exemption, as the case at hand indicates, defendants may also successfully sidestep BIPA liability in the event that they exclusively collect facial geometry from VTOT users without collecting any additional identifying information, such as names, email addresses, and phone numbers, among other things, from them.

The case is Celia Castelaz, et al., v. Estèe Lauder Cos., Inc., et al., 1:22-cv-05713 (N.D. Ill.)