A New York federal judge has sided with Hermès in the latest round of a closely-watched battle over trademarks and non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”). In a newly-released opinion and order, Judge Jed Rakoff of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York refused to certify Mason Rothschild’s appeal of a May decision, in which the court denied Rothschild’s motion to dismiss Hermès’s claims that he “violated” the Birkin bag-maker’s trademark rights by way of his headline-making MetaBirkins project. In his September 30 opinion, Judge Rakoff determined that the issues at play in Rothschild’s appeal are not so “exceptional” as to warrant immediate appellate review (“Interlocutory appeals should … be reserved for only the most exceptional circumstances,” the judge asserts), and thus, denied Rothschild’s motion in full.

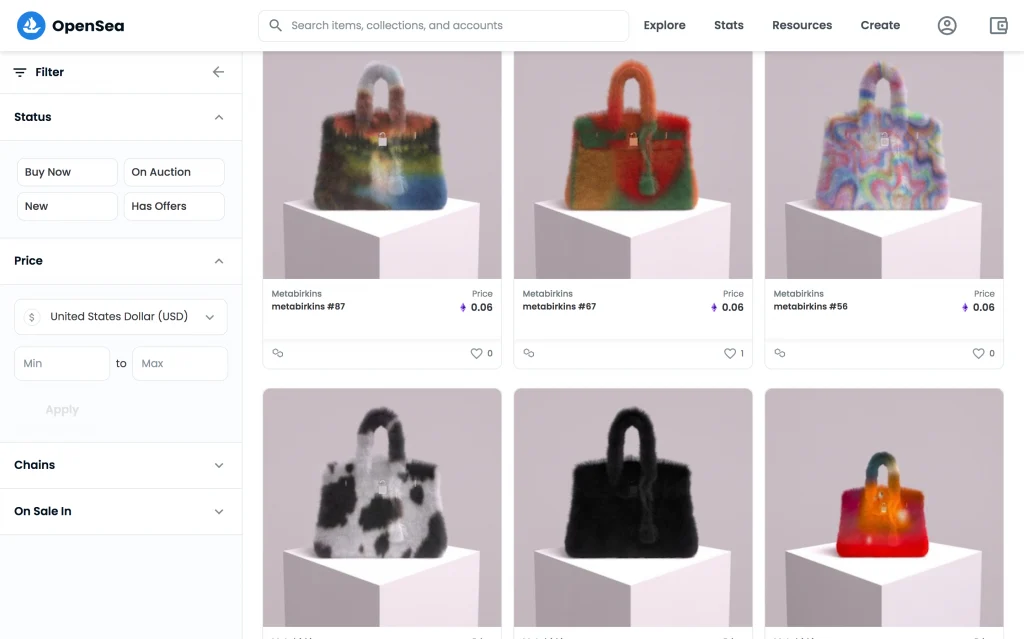

Setting the stage in his decision, Judge Rakoff states that the lawsuit centers on the “collection of digital images depicting faux-fur-covered Birkin handbags titled ‘MetaBirkins’” that Rothschild “designed and marketed” and then sold using NFTs. “Like the physical Birkin handbag itself, MetaBirkins are extremely valuable commodities,” the court asserts, noting that “the NFTs have sold for over a million dollars collectively.” As for the harm at play, the court maintains, echoing what Hermès alleged in its complaint, that “consumers and media outlets have expressed actual confusion as to whether Hermès is affiliated with Rothschild’s line of NFTs, with many believing it to be the product of a partnership between the two.”

In an order in May, the court refused to grant Rothschild’s motion to dismiss, in which he argued that Hermès’ trademark infringement claim should be tossed out given that the Birkin bag imagery is art protected by the First Amendment. (Despite applying the Rogers test, the court found that the “MetaBirkins” title may not be “artistically relevant,” and even if it is, Rothschild’s use of “MetaBirkins” may be explicitly misleading as to the source of the artwork.) The court also denied Rothschild’s argument that Hermès’s claims are barred by Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox, in which the Supreme Court held that only misrepresentations as to the source of tangible goods are actionable under the Lanham Act.

Against that background, Rothschild presented two issues in the order from the court this spring as appropriate for interlocutory appeal. The first issue was “Rothschild’s disagreement with the court’s determination that there are sufficient factual allegations in the amended complaint to survive a First Amendment challenge under the Second Circuit’s Rogers v. Grimaldi test.” The second issue was Rothschild’s argument that “the thrust of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dastar is to restrict the scope of the Lanham Act to the misuse of trademarks in the sale of tangible goods, whereas here, the goods are intangible. “

Reflecting on Rothschild’s argument on the Rogers front, Judge Rakoff claims in his Sept. 30 order that the MetaBirkins-maker took issue with his determination that Hermès makes sufficient allegations that his use of its trademarks was not artistically relevant to the NFTs. “The order’s failure to find artistic relevance is a legal error,” Rothschild urged in his appeal, making it “immediately reviewable.” Specifically, Rothschild claimed that “because ‘the threshold for artistic relevance is intended to be low,’ this issue functionally amounts to a question of law appropriate for interlocutory appeal.”

The court disagrees, stating that “an issue is not a legal one just because the defendant says it is,” and more than that, “an issue that involves the application of law to alleged facts is not, at bottom, a purely legal one.”

Taking this analysis “one step further,” Judge Rakoff finds that Rothschild’s arguments would still fail to persuade “even if one assumes he is seeking review on a purely legal issue … [because] a court that determines that the use of a trademark was ‘artistically relevant’ to the underlying work must still decide whether the defendant’s work was ‘explicitly misleading’ as to its source and thereby, not entitled to First Amendment protection.” Because reversing the court’s decision on the “artistic relevance” point would not, by itself, terminate the litigation, “interlocutory appeal is doubly unwarranted,” according to the judge.

In terms of the “explicit misleadingness” prong of the Rogers test, Rothschild also sought interlocutory review of the court’s ruling, arguing that the court erred in finding there are sufficient allegations in the amended complaint that his work is explicitly misleading, and second, that “the court should not have applied the Polaroid factors to assess consumer confusion because they are relevant only where the title of one work allegedly infringes the trademark of another work – so-called ‘title-vs-title’ conflicts.” (In shooting down Rothschild’s motion to dismiss, the court found that based on its application of the Polaroid factors, Rothschild’s use of “MetaBirkins” could be misleading if it caused consumers to believe that Hermès had authorized the infringing use.)

Judge Rakoff states again that “neither argument provides persuasive grounds for certifying an immediate appeal.” Rothschild’s first argument on this front “can be dismissed in much the same way as [his] earlier contentions,” the judge contends. As for Rothschild’s second claim, the judge asserts that “the bare question [of] whether to restrict the scope of the Polaroid factors to title-vs-title conflicts is not ‘controlling’ and thus, reversal on it would not, by itself, terminate the action.”

Moving on to Rothschild’s Dastar-centric claims, the court similarly shoots down Rothschild’s arguments here, stating, that he “cannot show that courts view the Lanham Act as restricted to claims against the misuse of trademarks involving tangible goods after the Supreme Court’s decision in Dastar.” Rothschild argued that because the MetaBirkins are “creative works and there is no copyright at issue – circumstances analogous to that of Dastar,” the Supreme Court’s decision “bars Hermès from bringing Lanham Act claims directed at intangible goods like his.”

One of the problems, per Judge Rakoff, is that “Dastar said nothing at all about the general applicability of the Lanham Act to intangible goods.” The judge contends that in Dastar, “the Supreme Court sought to underscore the subtle distinction” between copyright and trademark, the latter of which is “aimed principally at preventing confusion regarding consumer goods.” In other words, “neither Dastar nor its progeny require that a defendant’s goods be tangible for Lanham Act liability to attach.” Instead, the courts “draw a sharper distinction between copyright and trademark by requiring consumer confusion as to the defendant’s goods – whether tangible or intangible – rather than with respect to their creative content.”

Here, Rakoff contends that “it is plausible that the use of [Hermès’s] trademarks by Rothschild did generate consumer confusion with respect to the defendant’s intangible goods for sale – the MetaBirkins – and so, Dastar does not bar Hermès from pursuing its Lanham Act claims.” Unlike the plaintiffs in Dastar and related cases, “Hermès can reasonably contend that consumers would be confused about the source of Rothschild’s goods – not just their creative content – and more likely to buy those goods if they believed Hermès was associated with the project,” the court states. “These factual allegations, taken as true, make Dastar and its related cases entirely distinguishable.”

With the foregoing (and other reasons) in mind, Judge Rakoff ordered that Rothschild’s motion for interlocutory appeal on the court’s motion to dismiss order be denied in its entirety. The judge noted that in accordance with the current schedule, the parties are slated to be ready for a trial by November 4.

THE BIG PICTURE: The case is one of a number of web3-centric battles that brands and attorneys, alike, are keeping a close eye on, with “the court’s balancing act between trademark protection and First Amendment concerns,” in particular, “likely [to] influence both brand owners and artists, at least in the near future,” according to Stinson LLP’s Abigail Flored and David Kim. For example, they note that “many brand owners have already been racing to file trademark applications for the anticipated use of their marks with NFTs and/or virtual goods in the metaverse.” With consumers “becoming increasingly interested in digital experiences,” they say that “it is critical” for players in this space (and those eyeing an expansion into the virtual world) “to understand the metes and bounds of our intellectual property and actively police both the physical and digital world in order to keep up with any changes in technology and the law.”

The case is Hermès International, et al. v. Mason Rothschild, 1:22-cv-00384 (SDNY).