Dior’s quest to register the shape of its enduringly-popular Saddle Bag is facing more pushback. On the heels of filing a trademark application with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) a year ago for the “it” bag that John Galliano first conceived of in 1999 during his tenure with the French fashion house, and that has since been reintroduced (and heavily marketed) by Dior under the watch of current creative head Maria Grazia Chiuri, the LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton-owned brand’s application for registration has been preliminary shut down for a second time by the trademark office because the bag design consists of “a nondistinctive product design or nondistinctive features of a product design.”

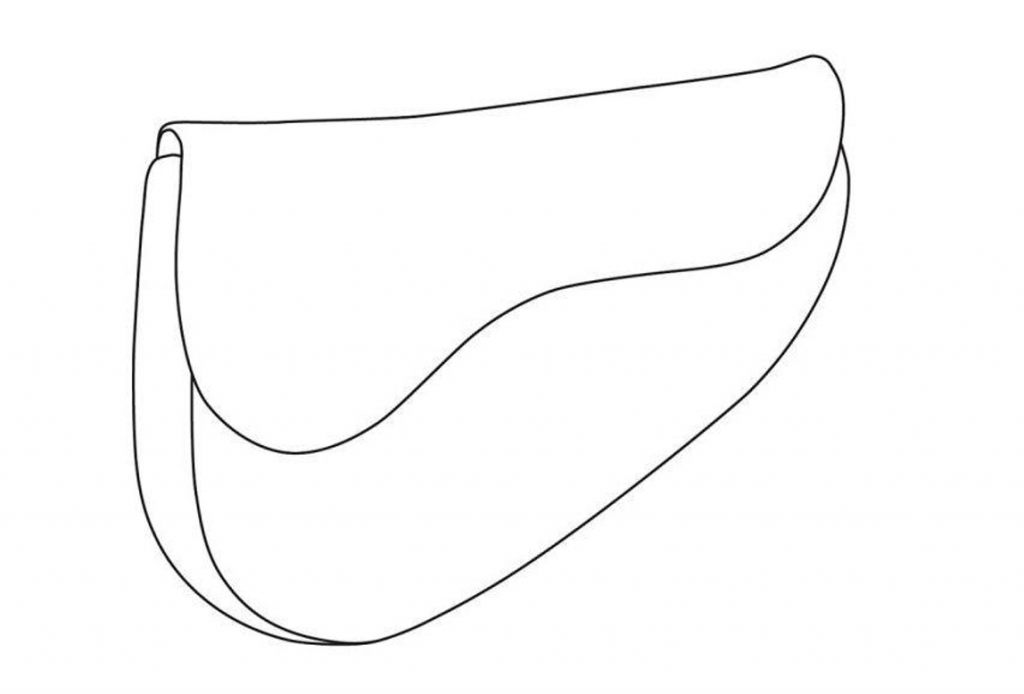

According to a March 9 Office Action from the USPTO, the second refusal letter from the national trademark body, Dior’s Saddle Bag mark – i.e., “the three-dimensional product design of a bag with a curved and sloping base, and a single flap with curved contours covering the opening of the bag” – is ineligible for registration on the USPTO’s Principal Register without Dior showing that the bag design has “acquired distinctiveness,” or in other words, without proof that as a result of Dior’s extensive use and promotion of the bag design, “consumers now directly associate [the design] with Dior.”

USPTO examining attorney John Mitchell sent Dior an initial Office Action in August, in which he refused to register the mark on the basis that it is a non-distinctive product design. While there are no “conflicting marks that would bar registration,” Mitchell wrote this past summer, the design of the 22-year old Saddle Bag was still barred from registration (at least preliminarily) because the mark consists of a product design, which “can never be inherently distinctive as a matter of law.” Citing the Supreme Court’s 2000 decision in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Mitchell stated that “consumers are aware that [product] designs are intended to render the goods more useful or appealing rather than identify their source.” As such, proof that the design functions as a trademark is a pre-requisite to registration.

More than that, in his first Office Action, Mitchell also took issue with Dior’s “inconsistent use” of the mark on several different types of goods. (Dior originally claimed rights in the design of the bag for use in Class 25, which covers clothing and footwear; Class 9, which extends to eyewear, “bags, satchels and covers for computers,” chains for eyeglasses, etc.; and Class 18 for leather goods). Mitchell stated in his August 2020 Office Action that “slight variations in appearance of a mark comprising a three-dimensional product design may be acceptable,” but only “if all products in a product line or series have a ‘consistent overall look’ such that (1) the product design conveys a single and continuing commercial impression, and (2) any changes to the product design do not alter its distinctive characteristics.”

In lieu of fighting this, Dior opted to remove its claims to “Classes 9 and 25 in their entireties, and amends Class 18 to restrict the identification of goods to ‘coin purses; bags in the nature of purses, clutches and handbags; handbags; leather clutch bags’ in Class 18,’” in response to the initial Office Action. (At some point between the application being filed and the second Office Action being issued, Dior also amended the description of the trademark from “a design of a tote” to “the three-dimensional product design of a bag with a curved and sloping base, and a single flap with curved contours covering the opening of the bag.”)

As for the USPTO’s refusal on “non-distinctive product design” grounds, Mitchell states in the most recent Office Action that instead of providing “evidence or arguments” showing that the shape of the Saddle Bag has achieved “secondary meaning” in the minds of consumers in its response in order to overcome the “nondistinctive product design” refusal, counsel for Dior responded with “a conclusory statement that ‘[Dior’s] applied-for-mark is distinctive and has become recognized as one of the most iconic bag designs in the world.’”

With that in mind, Mitchell stated in his March 9 letter that the “refusal is maintained because of a lack of evidence of acquired distinctiveness,” and that in order to overcome the remaining refusal, Dior will need to show that its mark has acquired distinctiveness. This can be achieved by way of “a prima facie showing of acquired distinctiveness based on five years’ use of the mark with related goods [since Dior filed its application on an intent-to-use basis], or actual evidence of acquired distinctiveness for the same mark with respect to the other goods.” More than that, Dior must also show “sufficient relatedness of the goods in the intent-to-use application and those for which the mark has acquired distinctiveness to warrant the conclusion that the previously created distinctiveness will transfer to the goods in the application upon use.”

Dior now has six months to respond to the Office Action and provide such proof in order to avoid having the application being deemed “abandoned.”