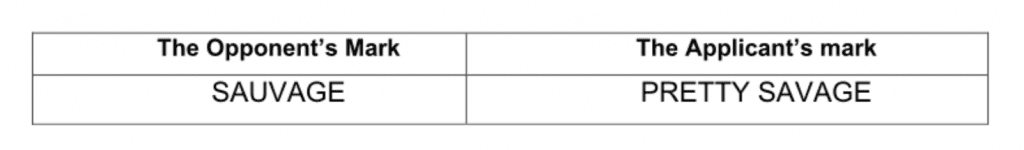

Christian Dior has been handed a loss in its attempt to block another party’s “confusingly similar” trademark from being registered. According to the opposition that Dior initiated with the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office (“UKIPO”) late last year, the “Pretty Savage” trademark application for registration that a Caterham-based woman named Adele Savage filed with the same trademark body for use on “soaps, hair care products, and exfoliants,” as well as soap holders and dishes, is too similar to its “Sauvage” cosmetics trademark, and thus, should not be registered. The trademark office disagreed.

In his August 4 decision, UKIPO Hearing Officer Matthew Williams sided with Ms. Savage and let her “Pretty Savage” application move ahead in the registration process, despite arguments from Dior to the contrary. The case got its start in late 2019 when Dior filed an opposition to Savage’s September 2019 application on the basis that it began using its “Sauvage” mark before Ms. Savage adopted her mark, and in fact, has maintained registrations of its own for “Sauvage,” including in the European Union and the UK, since as early as August 2015 for use of the mark on “perfumery products, cosmetic products, soaps, [and] shower gels,” among other products.

Sauvage v. Pretty Savage

As Dior argued in its opposition, as summarized by the UKIPO in its recent decision, “The parties’ marks are similar and that their goods are identical or similar such that there is a likelihood of confusion whereby the relevant public will believe that the marks are used by the same undertaking or think that there is an economic connection between [Dior and Ms. Savage’s company].” Williams revealed that the Paris-based brand also argued that its “Sauvage” mark “benefits from a reputation for the goods [at issue]” and thus, Savage’s use of the “Pretty Savage” mark “would take unfair advantage of, or would be detrimental to, the reputation and distinctive character of” its mark.

To be exact, LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton-owned Dior claimed that by using the “Pretty Savage” mark, Savage would be “trading on the back of [Dior’s] goodwill and reputation … and could increase its own sales of products bearing the mark … without having had to make the associated investment.” In short: Savage’s “marketing could be made easier by association with [the Dior] mark, thereby, gaining an advantage that is unfair.”

The potential “detriment” that could be caused by the “Pretty Savage” mark is heightened by the fact that Dior “has no control over [the unrelated company’s] activities or the quality of the goods” in connection with which the mark will be used, the brand claimed. More than that, Dior asserted that the use of the similar mark could cause “dilution and blurring of the distinctive character of [its] mark,” especially consumers cannot “quickly identify or accurately identify the source of” the unrelated parties products.

To establish the level of goodwill and reputation at play, Dior revealed that its annual advertising spend to “create and produce the advertising campaigns for Sauvage products” between 2014 and 2019, ranged from nearly 3 million euros ($3.53 million) in 2015 to over 6 million ($7.06 million) in 2016 to nearly 10 million ($11.76 million) by 2019. As for its “annual media investment specifically in the UK for Sauvage products between 2015 and 2019,” that sum amounts to 5.7 million pounds ($7.44 million) annually between 2016 and 2018, and over 7 million pounds ($9.13 million) in 2019.

In response to Dior’s opposition, Ms. Savage claimed that she has been using the mark to sell “handmade soap, bath bombs, and wax melts” since October 2018, and asserted that while there is a “likelihood that [Dior] has goodwill and reputation in the UK for ‘Sauvage’ in connection with men’s fragrance (only),” the markets for soap and men’s fragrances “are completely different,” thereby, leaving room for the potential that consumers might not be confused between her products and those of Dior.

Dior argued, nonetheless, that it is common for luxury brands (including Chanel, Tom Ford, and Hermès) to offer both fragrances and body products, including soaps.

Confusion, Dilution

Reflecting on the parties’ respective arguments, Williams determined that the requisite level of confusion and the risk of passing off are not present. In his decision, Williams noted that Dior’s “Sauvage” mark for use in Class 3, was, in fact, registered before Ms. Savage’s application for “Pretty Savage” was filed, and while there “is an overlap in the purpose of the goods … and there is likely to be an overlap in the relevant public and distribution channels, there are also differences in the physical nature and methods of use [of the respective parties’ products].”

Looking specifically to the differences between the two marks, Williams states that the overall impression of Dior’s mark “resides in the single word ‘Sauvage,’ which has no meaning in English.” Ms. Savage’s mark, on the other hand, “comprises the two ordinary English words, ‘Pretty’ and ‘Savage.’” With this in mind, and given Savage’s use of the word “Pretty” and the “addition of the extra letter ‘U’” in Dior’s mark,” the UKIPO Hearing Officer found that the respective marks “are visually similar to a low to medium degree.”

Ultimately, Williams found that “the differences between the marks” – two English words versus one French word – “are such that even were the marks [are] used in relation to goods that are identical, there will be no direct confusion.” In other words, there is “no likelihood that the average consumer … will mistake one mark for the other.”

He stated that this decision is dependent on the fact that not only does “the average consumer normally perceive a mark as a whole and does not … analyze its various details,” perfumery products are “typically bought with less frequency and at greater expense [than soaps and other toiletries], and may, therefore, engage a higher level of attention,” thereby, further removing the likelihood that consumers will be confused as to the source or (lack of) affiliation between Dior and Ms. Savage and their respective offerings.

Turning to dilution and passing off, Williams held that Ms. Savage’s applied-for mark does not give rise to an actionable risk of either, largely due to his finding that “the average consumer, on seeing the mark ‘Pretty Savage’ used in relation to soaps, wax melts, exfoliants, [etc.], will not call to mind, even fleetingly, Dior’s mark.” Because establishing that link “is a necessary component for success based on a [claim that the registration of the mark would “damage or be detrimental” to Dior’s reputable mark]” and a passing off claim, Dior falls short on both, per Williams.

With the foregoing in mind, the UKIPO states that Dior’s opposition has “failed on each of its grounds,” and Ms. Savage’s application “may proceed to registration in its entirety.” In addition to walking away with a loss, Dior may contribute to the costs that Savage had to pay to “defend her application,” an amount of nearly $2,300.

While there is an opportunity for Dior to appeal the UKIPO’s decision, it is not yet clear whether the brand will do so.