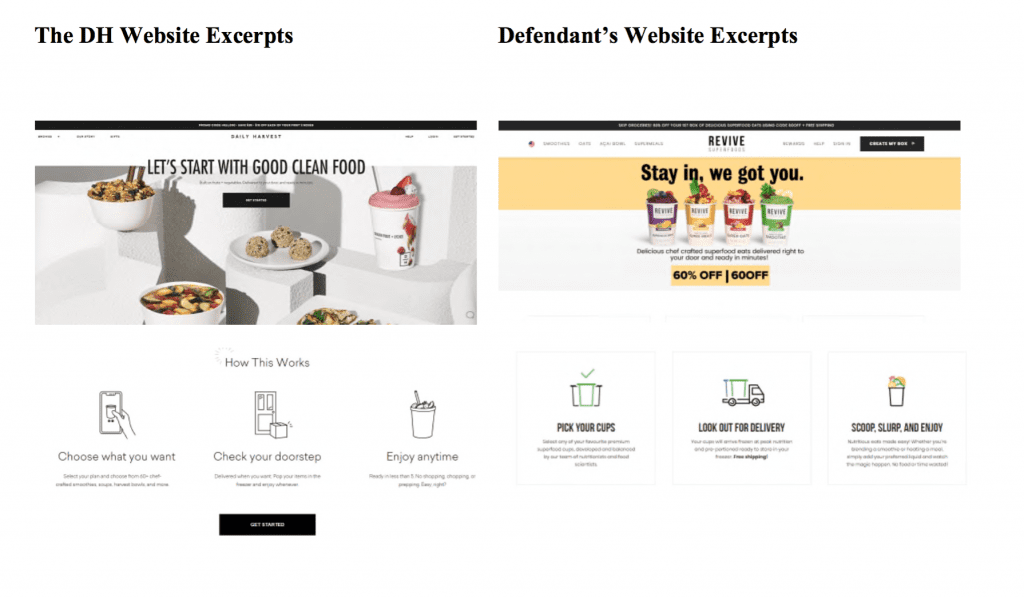

Daily Harvest and Revive Organics have reached a confidential settlement in the case that Daily Harvest filed in April, accusing its fellow frozen food subscription company of engaging in trademark and copyright infringement by allegedly adopting “an identical and confusingly similar website design, content, product packaging, [and] images.” In a notice of voluntary dismissal filed on December 22, Daily Harvest alerted the court that it was dismissing its claims “with prejudice against Revive Organics,” just a day after the court issued an order stating that it had been “advised that the parties have reached a settlement in principle.”

The short-lived case that Daily Harvest, the mighty and heavily funded direct-to-consumer (“DTC”) player, initiated against Canada-headquartered-but-expanding Revive was an interesting one in that it sheds light on and raises questions about the some of the core assets of consumer goods companies, namely, their valuable branding.

With that in mind, at the heart of the case was not the parties’ products. In fact, Daily Harvest did not actually claim that Revive copied any of its proprietary products, such as its “ready-to-blend smoothies, savory Harvest Bowls, hearty soups,” etc. Instead, the suit firmly centered on Revive’s alleged co-opting of the Daily Harvest brand. The lack of alleged copying of Daily Harvest’s products by Revive in furtherance of its scheme to “free-ride [on Daily Harvest’s] coattails” seems to suggest that the most valuable components are not the products, themselves. Instead, Daily Harvest’s most copy-worthy assets are the “distinctive” elements that (allegedly) enable consumers to link the website at play or the product packaging to a single – and increasingly-popular – source.

This emphasis on branding is, of course, not new to or exclusive to the DTC space, and in the DTC space, the products, themselves, certainly are not irrelevant. At the same time, though, it is difficult to ignore the fact that the distinguishing factor for many of these burgeoning young(ish) companies is not necessarily earth-shattering, impossible-to-get-elsewhere products. Marketing/strategy executive Ana Andjelic touched to this point this month, stating that venture capital firms “pour money into companies that do not offer a better product or operate better than the competition: they simply have more money to undercut competitors on price, gaining market share and advantage.”

In reality, what is driving much of the success of these entities is more likely carefully-crafted and highly-effective branding and (a sizable amount of) marketing that enables those branding features to function as trademarks. This can come in the form of a specific brand aesthetic, complete with certain repetitively-used – and ideally, Instagram-friendly – visual branding elements (Glossier’s pink packaging comes to mind); the consumer experience that a company provides, often via its e-commerce and m-commerce sites; and/or the specific messaging that is crafted around the brand. (In the DTC segment of the market, inclusivity and community, for instance, are pervasive messages, as is a communications strategy that centers on a sense of mission, regardless of the types of products at play).

Ultimately, what routinely proves compelling to consumers and drives them to buy into many of these VC-propelled companies (and others, including those in the luxury space) is not the offerings, themselves, or better yet, not the offerings on their own. It is the brand-centric aspects of a company and the messaging that surrounds them, which this case appears to clearly highlight.

Brands Protecting Websites

Against that background and given the sheer importance of a compelling and distinctive e-commerce (and m-commerce) experience, the issue of the protectability of “key” parts of companies’ branding – such as the design of the product packaging and the “look and feel” of a company’s e-commerce website – becomes of primary importance.

In this case, Daily Harvest argued that it maintains rights in the “unique and inherently distinctive” packaging that it uses, as well as the elements that make up its website – from the layout and some of the language to the “user shopping experience and interface design.” Its argument about the protectability of its site is in line – at least at a high level – with existing case law, such as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit’s 2014 decision in Fair Wind Sailing v. Dempster, holding that the defendant had infringed the trade dress of the plaintiff’s website.

Around the same time, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California determined in Ingrid & Isabel, LLC v. Baby Be Mine, LLC that the total look and feel of a website used to market and sell products and services can constitute protectable trade dress under the Lanham Act.

(Ingrid & Isabel argued that the combination of the “feminine … pink and orange script,” “pastel pink-orange hue,” “color and pattern of wallpaper,” and the particular poses of its models, which are used on its website are non-functional – and protectable – facets, and the court determined that Baby Be Mine’s intentional copying of those allegedly non-functional element was sufficient to create a triable issue of fact, and denied Baby Be Mine’s summary judgment motion.)

And more than that, Daily Harvest’s claims are a demonstration of an ongoing shift among brand owners to look to trademark law (as opposed to copyright law) for protection of websites.

Just as striking as the trade dress rights that Daily Harvest clams in connection with the user interface of its website, an area of trademark law for which the bounds are still somewhat undefined, is a joint letter that parties filed with the court back in July, in which Revive set out some preliminary arguments of its own that could prove to be informative for brands forced to defend themselves against website-specific trade dress claims in the future.

Primarily, Revive asserted that Daily Harvest’s alleged website trade dress is not distinctive, “meaning that the design of the website itself is not an indicator of source.” Aside from the Daily Harvest name, Revive argued that Daily Harvest’s “website is a compilation of common ornamental and functional features that are neither inherently distinctive nor have they acquired distinctiveness.” In case that is not enough, Revive claimed that Daily Harvest’s alleged website trade dress is invalid because “the vast majority of its listed elements are functional and, even when combined with ornamental elements, cannot serve as part of its protectable trade dress.”

Examples of the functional components that Daily Harvest claimed as part of its protectable trade dress? “Crisp white backgrounds,” “modern and sleek black font,” brand names “centered at the top of a homepage,” “sleek black banners,” “colorful photograph[s] of a line up [of the products sold on the website] with garnishes,” “categories of products displayed horizontally in black font,” displaying ingredients in a “transparent cup” so they can be seen, “photograph[s] from a head-on view perspective as if ready for the consumer to enjoy,” “subpages featuring rows and columns of product images” and “textual description[s] of the product, with a summary of the benefits delivered.” These things “are ubiquitous on websites and designed to make it easier to read the contents of the website,” Revive argued, and thus, are not protectable.

Finally, Revive contended that “even if Daily Harvest could prove a protectable trade dress in its website,” it cannot show that consumers visiting Revive’s website are likely to confuse its products with Daily Harvest’s. Pointing to a 2004 decision from U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in the Louis Vuitton Malletier v. Dooney & Bourke case, Revive asserted that “the prominent use of … brand names throughout [the respective companies’] websites is itself powerful evidence that confusion is unlikely.”

Revive noted that its site “significantly, contains the name REVIVE SUPERFOODS on every single page,” and that Daily Harvest, in order “to clearly identify its source … uses the name DAILY HARVEST prominently all over” its site, as well.

Revive’s points in the July letter – and the since-settled lawsuit more generally – raise some relevant issues about the protectability of website designs (in the DTC space and beyond), including “the user shopping experience and design interface,” particularly in light of the fact that websites are coming to look more and more alike (due, in part, to functional constraints), and as companies come to rely more and more on e-commerce and m-commerce both in light of onset and enduring impact of COVID-19 and almost certainly, in a post-pandemic world, as well.

Given the evolving nature of the website-as-trademark claim, it would have been interesting to see how to court handled the arguments in this case. Regardless of the outcome, it seems obvious that proving protectability of a specific trade website dress – and defending against such claims of infringement – would call for deep-pockets.

*The case is Daily Harvest, Inc., and Rachel Drori, v. Revive Organics, Inc., 1:20-cv-03087 (SDNY).