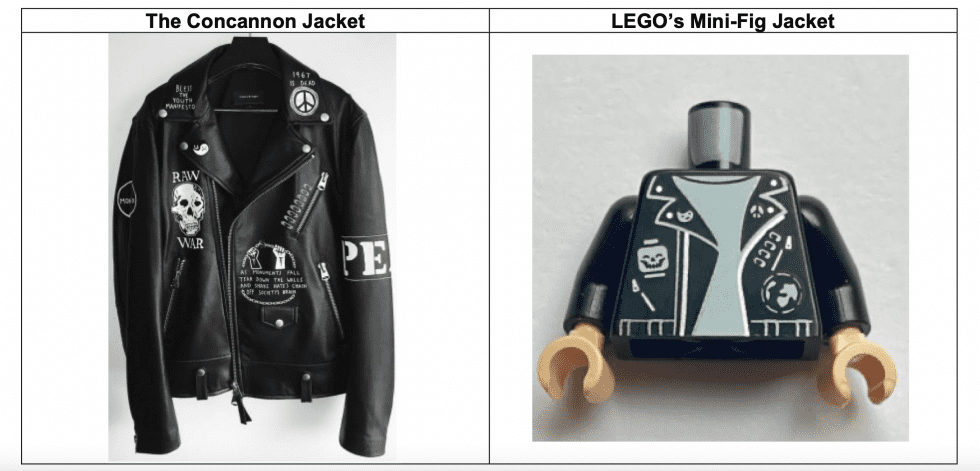

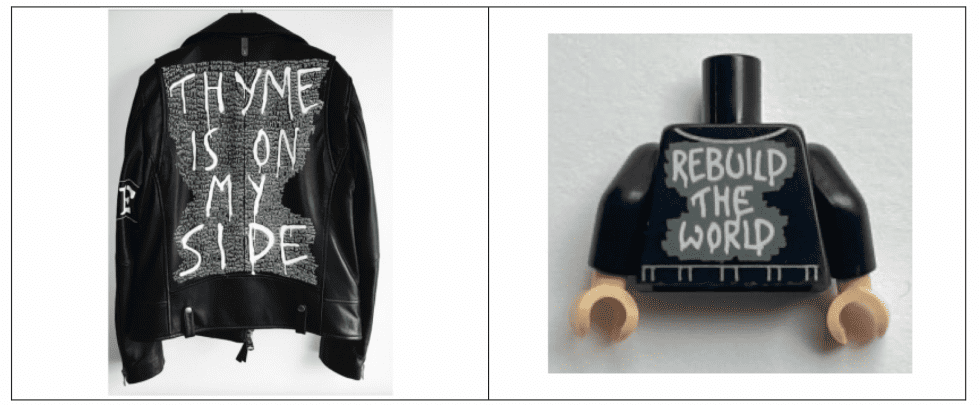

A federal court in Connecticut has refused to toss out the lawsuit that a designer is waging against LEGO, accusing the Danish toy giant of co-opting the design of a leather jacket that he created for Queer Eye cast member Antoni Porowski and replicating it for a figurine in its own Queer Eye-themed set – albeit without his authorization. In the most recently amended complaint that he filed in a Connecticut federal court in July, James Concannon claims that LEGO copied his “signature style and brand” – which consists of “short, provocative statements in hand-painted, graffiti-style lettering” that appear on t-shirts, jackets, and accessories – and in doing so, ran afoul of his trademark rights in the design, which he says serves as an indicator of source, and of his rights in “the unique placement, coordination, and arrangement of the individual artistic elements,” for which he maintains a U.S. copyright registration.

In response to Concannon’s trademark and copyright claims, counsel for LEGO argued that the lawsuit should be dismissed. In particular, LEGO asserted that Concannon’s copyright infringement claim should be dismissed given that it has “a valid license that permits use of the jacket, or in the alternative, that its actions constitute fair use.” His trade dress and unfair competition claims also fall short, per LEGO, as he has failed to plead a prima facie trade dress infringement claim. Still yet, LEGO maintains that because Concannon has failed to plead a claim for direct copyright infringement, his contributory and vicarious copyright claims should be dismissed, as well.

In a decision on Wednesday, Judge Janet Bond Arterton of the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut, refused to grant LEGO’s motion to dismiss Concannon’s case.

Copyright Infringement – The court first looked at LEGO’s defenses to Concannon’s copyright infringement claim, namely, that: (1) it has an implied non-exclusive license to use the jacket design because Concannon gifted the jacket to Porowski knowing that he was likely to wear it Queer Eye, thereby, granting Netflix a license to use the jacket in “any manner it pleased – including sub-licensing the work to LEGO;” and (2) its use of the jacket in the LEGO set constitutes fair use.

In terms of the potential license, the judge found that she “does not currently have sufficient factual info. on the face of the complaint to determine whether the license existed, and thus, says that dismissal on this basis is “unwarranted.” While Concannon saw that Porowski wore the jacket on an episode of Queer Eye before the LEGO set was released and did not take legal action, “that alone is not enough to infer that he intended for it to be copied and distributed, or that he and Mr. Porowski had any common understanding of how the jacket would be used,” according to the court. Moreover, Concannon alleges that he did not and “he had no reason to believe based on his prior dealings with Porowski and Netflix” – that the jacket would be used by LEGO to create a new product.

In an attempt to evade this conclusion, the court noted that LEGO points to the outcome in Solid Oak Sketches, LLC v. 2K Games, Inc., in which a New York federal court found that the inclusion of tattoo designs in a videogame to depict the likeness of an athlete constitutes fair use. The court distinguished the facts of that case and the case here, stating that in Solid Oak Sketches, the tattoo artists “plainly stated that they ‘intended the players to copy and distribute the tattoos as elements of their likenesses,” whereas Concannon “has made no such admission [here], nor can his consent be implied from his silence, alone.”

As for fair use, the court was similarly unpersuaded, finding that “factual issues remain as to the purpose, character, and nature” of Concannon’s jacket design and the LEGO figure jacket. Among other things, Judge Arterton asserted that “without materials such as affidavits or depositions to draw on, it would be premature for [her] to decide whether [LEGO’s] purpose [for recreating a similar jacket design] was accurate portrayal of Mr. Porowski, exploitation of the original work’s values, or something else,” such as “exploiting the creative values of the jacket,” as Concannon argues. Meanwhile, the court determined that the remaining fair use factors do not weigh in LEGO’s favor.

Trade Dress Infringement – Turning to Concannon’s trade dress infringement claim, Judge Arterton stated that when such a claim is based on the product’s design, the plaintiff must show “(1) non-functionality, (2) secondary meaning, and (3) a likelihood of confusion,” and it must also offer “a precise expression of the character and scope of the claimed trade dress,’ and describe the elements of design with specificity.” Here, Concannon contends that his trade dress includes “three distinct elements that appear in both his ready-made and his custom pieces: ‘short, provocative phrases; satirical commentary on punk rock and mainstream pop culture; hand-painted graffiti-style lettering.’”

Interestingly, LEGO has argued that differences in the phrasing of Concannon’s trade dress definition in his third amended complaint, such as using “short, provocative statements” in one section, and “unique combination of provocative, tongue-in-cheek phrases relating to pop culture” or “pop culture pun” in others, demonstrates a “failure to articulate a single definition.”

(Failure to clearly and consistently articulate what the trade dress consists of is not an uncommon roadblock, with courts opting to toss out infringement claims in response to imprecise pleadings by plaintiffs in trade dress litigation. The MZ Wallace v. Fuller case comes to mind, as the court held there that “while MZ Wallace submitted evidence of some attempts to enforce its rights against third parties, a fact that would support a showing of secondary meaning, the trade dress described in the cease-and-desist letters sent to these brands is inconsistent and often contains significant variations from that proposed in this case.”)

Siding with Concannon again, the court said that “at this stage,” it accepts Concannon’s trade dress definition for two reasons: First, the definition is “sufficiently specific,” and allows the court “to determine by visual inspection whether each item of clothing falls within the proposed definition” of the trade dress. “Some variation in the phrasing used to describe the trade dress is not fatal to the definition,” the court asserted, as “the product’s trade dress is not, in a legal sense, the combination of words which a party uses to describe or represent [its] ‘total image,] [but] rather, the trade dress is that image itself, however it may be represented in or by the written word.”

Judge Arterton further stated that “at least one court has found that even ‘pictures in the complaint’ were sufficient to convey the ‘overall image’ of a trade dress,” noting that Concannon’s photos in the amended complaint “sufficiently pled that his product line makes use of the elements he claims as part of his trade dress.”

Second, the court determined that Concannon proposed an adequately specific trade dress, as he also alleges in the complaint that “the defined elements are distinctive ‘because no other artist or designer has released a line of clothing containing this unique combination of specific elements.’”

In addition to setting forth a sufficient trade dress definition, the court found that Concannon adequately pled secondary meaning and likelihood of confusion (three of the eight Polaroid factors weigh in his favor at this stage, according to the court, and several require further factual development before the court can fully evaluate them) to show a plausible trade dress infringement claim, and thus, the court refused to toss out the claim.

As for the merits of the case, lawyer and intellectual property researcher Mike Dunford previously dove in, pointing to issues on the damages front (namely, that while Concannon’s copyright was registered in November 2021, the use by LEGO predates that, ruling out statutory damages and attorney’s fees), and the extent to which the jacket is actually protectable given that “the allegedly infringed work is the art on the jacket, separated from the jacket,” itself, as copyright law only protects creative elements that are separable from a useful article, such as a jacket. (This was the big takeaway from the Supreme Court’s 2017 decision in the Star Athletica case.)

From a copyright POV, Dunford says that the case hinges on whether or not the court finds that the “unique placement, coordination, and arrangement” of the elements that appear on the jacket are, in fact, “protectable and infringed notwithstanding the substitution of different individual artistic elements.” It is worth noting, of course, that since filing his lawsuit against LEGO back in 2021, Concannon added a trademark infringement claim, which also raises some interesting questions, including the extent to which the allege trade dress serves as an indicator of source, as opposed to as a decorative feature of the products upon which it appears.

The case is Concannon v. Lego Systems Inc., 3:21-cv-01678 (D. Conn).