A California federal judge granted North Face and its owner VF Corp’s April 26 motion to dismiss the trademark infringement complaint that Leonard McGurr – aka Futura – filed against them early this year, alleging that North Face “inexplicably began using a copy of” his famous “atom” design as the logo for a new line of apparel and fabric technology in 2019 “without [his] consent.” McGurr – who filed suit with the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California in January – claimed that he “has become known for a signature element that appears over and over in his work: a particular stylized depiction of an atom,” which he has used repeatedly over the past fifty years “as a traditional logo, to identify himself as the source of consumer products he offers, including apparel.”

In response to the suit, VF and co. took issue with the validity of McGurr’s atom mark, claiming that the “spherical atomic symbol” is not a valid trademark because “(1) it is aesthetically functional; (2) it is merely ornamental based on its size, location, and dominance on the goods on which it is placed; (3) it does not identify a ‘secondary source;’ and (4) it is purely artwork,” and thus, “does not function as a source identifier,” which is the primary function of a trademark. Beyond that, the defendants argued that this spring that the McGurr’s case should be tossed out of court because the artist “does not use his design in a consistent fashion,” and instead, the atom symbol is “not a singular design but the representation of a concept with a limitless number of iterations.”

As Judge Stanley Blumenfeld set out in his June 1 decision, McGurr states in his complaint that he “was an early adopter of a ‘fluid trademark’ – i.e. one with different iterations that feature enough of a family resemblance that the target audience can recognize it in all its variation.” The problem with this, according to the court, is that McGurr “cites no legal authority endorsing a theory of fluid trademarks,” and at the same time, “this Court [is not] independently aware of any judicial or USPTO finding of trademark protection based on a collection of similar but different designs.”

While McGurr is correct in his assertion that “there are no formal limitations on what can function as a trademark,” with Judge Blumenfeld noting that “things such as colors, flavors, and fragrances can be trademarks if they are non-functional and serve as a source identifier,” he states that McGurr, nonetheless, “cannot seek refuge in this broad principle” in order to protect a “style.”

According to the court, McGurr “does not purport to have a single distinctive identifier that serves as his trademark,” and instead, he asserts “trademark protection to control the commercial use of a spherical atomic symbol,” an assertion that Judge Blumenfeld says “is extraordinary in its seemingly boundless application – boundless because the purportedly protected symbol need not be accompanied by any word, name, product, or any other source identifier to run afoul of the alleged trademark, and boundless because the design of the spherical atomic symbol is ‘fluid.’”

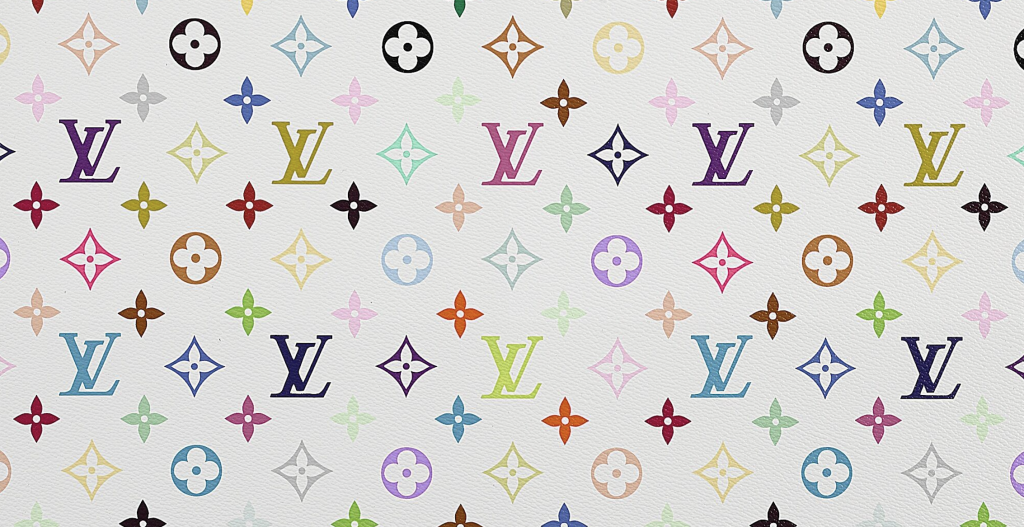

Pushing back against McGurr’s attempt to rely on trademark protection in connection with the “spherical atomic symbol,” Judge Blumenfeld held that “[b]asic geometric shapes, basic letters, and single colors are not protectable as inherently distinctive.” Citing a “useful point of contrast,” the judge notes the Louis Vuitton Malletier v. Dooney & Burke, Inc. case, in which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit found that Louis Vuitton had a trademark in the “Multicolore” pattern that introduced in 2002 in collaboration with artist Takashi Murakami, which was a colorful play on “the brand’s famous [brown and gold] Toile Monogram, featuring entwined LV initials with three motifs: a curved diamond with a four-point star inset, its negative, and a circle with a four-leafed flower inset.”

In its 2006 decision, the Second Circuit concluded that “Louis Vuitton’s Multicolore mark, consisting of styled shapes and letters – the traditional Toile mark combined with the 33 Murakami colors – is original in the handbag market and inherently distinctive.”

Ultimately, McGurr’s “novel theory of fluid trademarks, if permitted as proposed here, would give new meaning to federal trademark law with far-reaching consequences,” according to Judge Blumenfeld, who granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss, but also gave McGurr the opportunity to amend his pleading “to specify a distinctive mark, composed of a symbol next to his commercially famous name.” Counsel for McGur has until June 14 to file an amended complaint.

The case is Leonard McGurr v. The North Face Apparel, V.F. Corp., et al., 2:21-cv-00269 (C.D. Cal.)