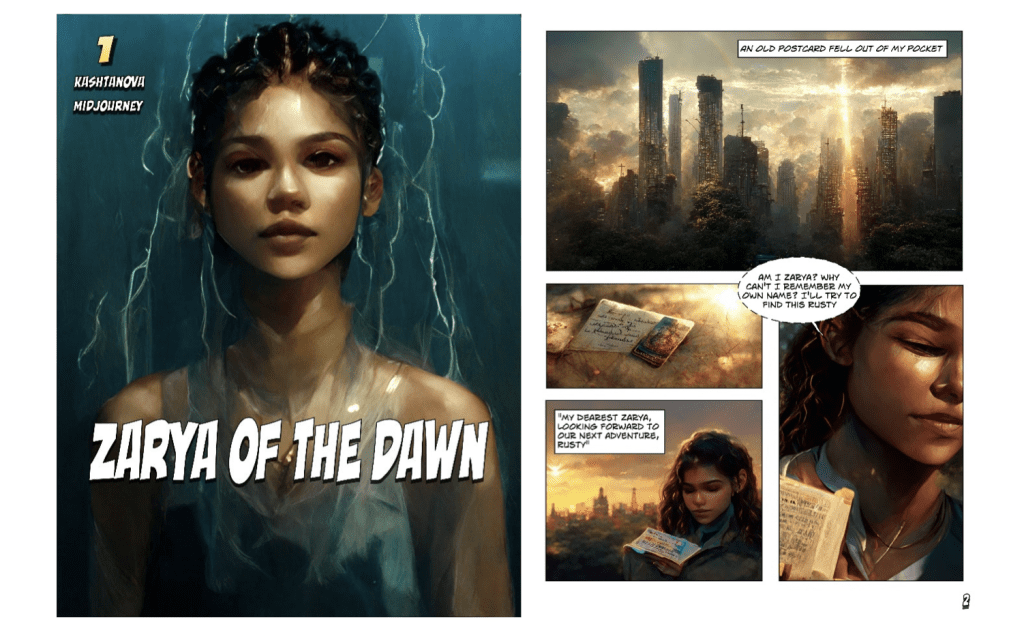

Images created by artificial intelligence (“AI”) generators are not eligible for copyright registration, the U.S. Copyright Office has confirmed. On the heels of issuing a copyright registration last year for a graphic novel called “Zarya of the Dawn,” the Copyright Office sought clarification from creator Kristina Kashtanova about her use of image-generating AI software in light of widespread media attention to the fact that while Kashtanova wrote the text of the book, she used AI image-generator Midjourney to create the images, which she did not disclose in her copyright application.

As part of the notice that the Copyright Office sent to Kashtanova back in September 2022, shortly after it registered the Zarya novel, it asked her to provide additional information, namely, about the extent to which there was human involvement in the process of creation of this graphic novel (the “work” or “Zarya novel”). The level of human – versus AI – involvement is significant, as copyright registrations in the U.S. have been reserved for works of human authorship. Against this background, the Copyright Office can cancel a registration if the authorship is insufficiently creative and/or if the work does not meet the established authorship requirements.

After reviewing Kashtanova’s original copyright registration application, as well as the relevant correspondence in the administrative record, the Copyright Office’s Associate Register of Copyrights Robert Kasunic alerted Kashtanova’s counsel in a letter dated Feb. 21 that while she “is the author of the work’s text, as well as the selection, coordination, and arrangement of the work’s written and visual elements [and] that authorship is protected by copyright,” the images in the work that were generated by the Midjourney technology “are not the product of human authorship,” and thus, not protected.

“Because the current registration for the work does not disclaim its Midjourney-generated content, we intend to cancel the original certificate issued to Ms. Kashtanova and issue a new one covering only the expressive material that she created,” Kasunic stated in the letter, noting that the “reissuance of the registration certificate will not change its effective date.” Meanwhile, the public record “will explain that the cancelled registration was replaced with the new, more limited registration.”

By back of background, Kasunic summarizes the legal principles that guide the Copyright Office’s analysis of the Zarya novel, stating in his letter that “courts interpreting the phrase ‘works of authorship’” – in the Copyright Act – “uniformly limited it to the creations of human authors.” For example, in Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, the Supreme Court held that “photographs were protected by copyright because they were ‘representatives of original intellectual conceptions of the author,’ defining authors as ‘he to whom anything owes its origin; originator; maker; one who completes a work of science or literature.’”

In cases where non-human authorship is claimed, Kasunic asserts that “appellate courts have found that copyright does not protect the alleged creations,” pointing to the decision in Urantia Found. v. Kristen Maaherra, in which the Ninth Circuit held that “a book containing words ‘authored by non-human spiritual beings’ can only gain copyright protection if there is ‘human selection and arrangement of the revelations.’” Still yet, Kasunic states that the Copyright Office “collects its understanding of the law in the Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices,” which “explains that [it] ‘will refuse to register a claim if it determines that a human being did not create the work.’”

Turning to the Zarya novel, Kasunic breaks down its various elements, finding that text, along with “the selection and arrangement of images and text” are protectable, while the imagery and at least one of the edited images is not.

Text of the Work – Kasunic says that he agrees with Kashtanova’s counsel that the text of the work is protected by copyright given that “the text of the work was written entirely by Kashtanova without the help of any other source or tool, including any generative AI program.” Based on this statement, which was provided in response to the Office’s request for additional information, “the Office finds that the text is the product of human authorship” and that it “contains more than the ‘modicum of creativity’ required for protection,” making the text of the work registrable

Selection & Arrangement of the Images/Text – Kasunic says that the Copyright Office “also agrees that the selection and arrangement of the images and text in the work are protectable as a compilation,” noting that Kashtanova states that she “‘selected, refined, cropped, positioned, framed, and arranged’ the images in the work to create the story told within its pages.” Specifically, he says that the Office finds the work to be “the product of creative choices with respect to the selection of the images that make up the work and the placement and arrangement of the images and text on each of the work’s pages,” and thus, copyright “protects Ms. Kashtanova’s authorship of the overall selection, coordination, and arrangement of the text and visual elements that make up the work.”

The Individual Images – This is where the big change comes, with the Office requiring that the images be disclaimed in the registration because they “are not original works of authorship protected by copyright.” Setting the stage here, Kasunic notes that “Midjourney offers an artificial intelligence technology capable of generating images in response to text [prompts] provided by a user.” It is relevant here, he says, “that, by its own description, Midjourney does not interpret [user] prompts as specific instructions to create a particular expressive result.”

The process by which a Midjourney user “obtains an ultimate satisfactory image through the tool is not the same as that of a human artist, writer, or photographer,” according to Kasunic, who states that “the initial prompt by a user generates four different images based on Midjourney’s training data.” While additional prompts applied to one of these initial images “can influence the subsequent images, the process is not controlled by the user because it is not possible to predict what Midjourney will create ahead of time.”

As for Kashtanova’s description of the creation of the Zarya novel images, she told the Office that she “‘guided’ the structure and content of each image” by entering a text prompt into Midjourney, picking one or more of the output images to further develop, “tweak[ing] or chang[ing] the prompt as well as the other inputs provided to Midjourney” to generate new intermediate images, and ultimately, the final image. To obtain the final images, Kashtanova says that she engaged in a “process of trial-and-error, in which she provided ‘hundreds or thousands of descriptive prompts’ to Midjourney until the ‘hundreds of iterations [created] as perfect a rendition of her vision as possible.’”

Reflecting on the process described by Kashtanova, Kasunic states that it is “clear that it was Midjourney – not Kashtanova – that originated the ‘traditional elements of authorship’ in the images.” Rather than being “a tool that Kashtanova controlled and guided to reach her desired image, Midjourney generates images in an unpredictable way,” per Kasunic. Accordingly, users of Midjourney’s AI software “are not the ‘authors’ for copyright purposes of the images the technology generates.”

Kasunic further states that “the fact that Midjourney’s specific output cannot be predicted by users makes Midjourney different for copyright purposes than other tools used by artists.” This is distinct from “editing or other assistive tools” in connection with which artists “select what visual material to modify, choose which tools to use and what changes to make, and take specific steps to control the final image such that it amounts to the artist’s ‘own original mental conception, to which [they] gave visible form.’” As such, users of Midjourney “do not have comparable control over the initial image generated, or any final image.”

The fact that Kashtanova “expended significant time and effort working with Midjourney” does not change this, per Kasunic, who notes that “courts have rejected the argument that ‘sweat of the brow’ can be a basis for copyright protection in otherwise unprotectable material.”

Edited Images – Finally, the Office refuses registration for Midjourney-authored images that Kashtanova “personally edited.” One of those photos, in which Kashtanova made changes to Zarya’s mouth, “are too minor and imperceptible to supply the necessary creativity for copyright protection,” according to Kasunic. As for the other, which Kashtanova created “‘using both the Midjourney service and Photoshop together,’ with edits in Photoshop made to ‘show aging of the face, smoothing of gradients, and modifications of lines and shapes,’” the Office found that it could not “determine what expression in the image was contributed through her use of Photoshop as opposed to generated by Midjourney.” However, “to the extent that [she] made substantive edits to an intermediate image generated by Midjourney,” the Office found that “those edits could provide human authorship and would not be excluded from the new registration certificate.”