Moda Operandi and Conde Nast have landed a few wins in the latest round of an ongoing lawsuit accusing them of using images of nearly 50 models in order to sell runway garments and accessories without those models’ authorization. On the heels of the high fashion retailer and the magazine publisher pushing back against the models’ false endorsement and Right of Publicity claims by way of respective motions to dismiss, a court has stripped down the case, dismissing all of the models’ false endorsement claims against Conde Nast, more than a dozen of the models’ false endorsement claims against Moda Operandi, and most of the models’ Right of Publicity claims against both defendants in a case that could have noteworthy implications for certain fashion advertising going forward.

Filing suit in a New York federal court in September 2020, dozens of Next Management-represented models – including Abby Champion, Grace Elizabeth, Grace Hartzel, Linsiey Montero, Anna Cleveland, and Binx Walton, among others – allege that in furtherance of a commercial arrangement, Moda Operandi and Vogue used photos and videos of them walking in seasonal runway shows in order to “steer traffic” to Moda Operandi’s e-commerce site, where consumers can then purchase the specific runway looks, all without “seek[ing] or obtain[ing] their prior written consent” from the models or paying them for such use of their images.

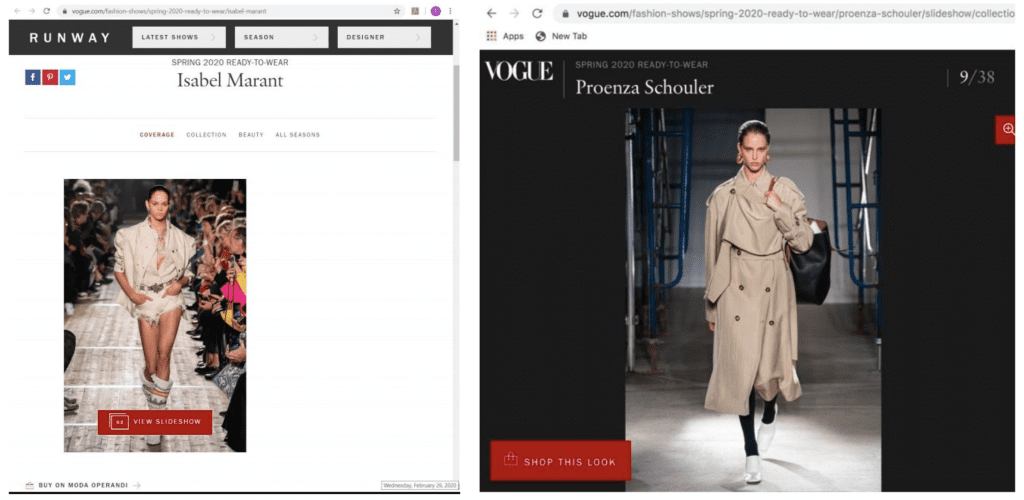

In a nutshell: The models allege that they are “routinely hired by companies for their modeling services to sell products,” and as a result, when Condé Nast and Moda Operandi include links that enable consumers to “Shop This Look” next to images of them on the runway (which, interestingly, no longer appear on Vogue’s site), “the general public is likely to be, and has been, deceived and/or confused into thinking that the plaintiffs have provided their respective sponsorship or approval to the services offered by Moda and Vogue.”

False Endorsement

In response to the models’ suit, Conde Nast and Moda argued early this year that the models failed to make their case for a number of reasons, including because Conde Nast’s use of the photos is protected by the First Amendment, and given that “Moda’s typical consumers” will understand the use of the images not meant “to imply source, sponsorship, or endorsement of Moda or its products,” and thus, will not be confused into believing that the models are endorsing or associated with it and/or its e-commerce website.

Fast forward to late last month, and a New York federal court agreed to toss out an array of the claims set out in the models’ “unnecessarily long complaint,” a bulk of which center on the allegation that the defendants’ use of photos of the models is likely to cause consumers be confused or to draw the mistaken inference that the models “have provided their respective sponsorship or approval to the services offered by Moda Operandi and Vogue.”

There are a few problems with this premise, Judge Colleen McMahon stated in a memo and order dated September 22. Among them is the court’s view that this is “a classic right of publicity” scenario, but that the many non-New York-domiciliated models have turned into a false endorsement case is “a blatant effort to federalize a state law claim and extend its reach to individuals who have no rights under this state’s law.” (More about that later.) Beyond that, the court takes issue with the false endorsement claims, as “Vogue’s Runway [vertical] is an expressive work.” While the court “does not question the undeniable fact that the reference to ‘Buy on Moda Operandi’ on the ‘home’ page of each designer’s segment of the Runway [vertical], as well as the ‘Shop This Look’ link to Moda’s website on the individual pages of the slide show, have a commercial purpose,” Judge McMahon is clear that the “purpose of the Runway [vertical], as a whole, is not commercial.” Instead, it is “to report and comment on the season’s various runway collections.”

Additonally, the court found that Conde Nast’s “use of the plaintiffs’ images is artistically relevant,” which should not be surprising, as “the threshold for ‘artistic relevance’ is deliberately low and will be satisfied unless the use ‘has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever.’” There is “no question that Vogue’s use of the photos, taken on the runway, in a summary document about the season’s new fashions intends an ‘artistic’ and non- commercial purpose,” the court stated, noting that Vogue’s use of the photos does not “explicitly mislead as to the source or content of the work.” As such, Conde Nast’s use of the imagery “easily falls within the safe harbor of the Rogers test,” and thus, the publisher is shielded from the models’ false endorsement claims by the First Amendment.

Turning its attention to the false endorsement claims waged against Moda, the court states that the claims “are in some ways similar to those against Conde Nast – and in some highly significant ways are not.” Namely, “there is no question of journalism or application of the Rogers test to Moda’s use of the plaintiffs’ photos,” as the e-commerce company “displayed the runway pictures on its website for one reason only: to show off clothing it had for sale.” Nonetheless, the court held that “many of the claims against Moda can be dismissed.”

For instance, the court agreed to dismiss at least six of the models’ false endorsement claims against Moda because the record “does not adequately allege that pictures of [those] plaintiffs appeared on Moda’s website at all.” Those models argued that “Moda should [still] be liable for the use of their photos on Vogue’s website.” However, since Vogue’s use of the photos “is constitutionally protected and does not violate the Lanham Act,” the court held that “there is no ‘infringement’ by Conde Nast for which Moda could be held liable to plaintiffs on a theory of ‘contributory infringement.’”

The court also put a stop to a number of the other models’ false endorsement claims, as the individual models are not readily identifiable in the photos either because the photos show them from behind or among a group of models, or the photos were cropped and thus, do not show the models’ faces. Such use does not form the basis for a false endorsement claim, according to Judge McMahon, as the models “cannot be recognized by a viewer of Moda’s website,” and so, “consumers would not infer that an unknown model was ‘endorsing’ a product.” On this same front, the court stated that “the very fact that their faces are not identifiable renders the allegation that Moda intended to trade on the good will associated with their personas totally implausible.”

As for the remaining 25 models whose false endorsement claims against Moda that were left intact, Judge McMahon said that she was still not convinced that they will ultimately prevail. Specifically, the judge said that she has doubts when it comes to misrepresentation of fact, which is the second element in a false endorsement claim. The models (somewhat head-scratchingly) argue that the use of photos of them from the runway shows that appears on Moda’s website “falsely represent that [they] are endorsing Moda as their preferred place to purchase the clothes they are modeling – in other words, that [they] are working for Moda.”

Judge McMahon stated that she views this argument as “highly unlikely to succeed.” However, since it is “at least plausible” that, by featuring the models’ faces on its website, Moda has confused consumers, the court has enabled the claim to remain.

(In addition to the court’s reasonable skepticism about whether consumers would believe that the use of runway photos by both Vogue and Moda suggests that the models are endorsing Moda (which does seem like a potentially far-fetched argument given the context of the photos), it is worth noting – that in reviewing the Polaroid factors in connection with the models’ false endorsement claims against Moda (which the court says could ultimately weigh in favor of the models), Judge McMahon held that the second factor, sophistication of audience, “favors Moda, as it is unlikely that individuals who can afford to” – or are in the habit of “purchas[ing] designer clothing and who follow fashion design would be easily misled about what it was that the plaintiff models were, and were not, doing.” This is likely an accurate assumption, as well, given the nature of the typical Moda client.)

Right of Publicity

In addition to false endorsement claims, Judge McMahon states that all 43 plaintiffs assert Right of Publicity claims against both Conde Nast and Moda, as “they do not want their photographs not to be used by Conde Nast or Moda,” but instead, “want to be paid for the use of their visages in connection with the sale of the clothing they modeled.” As such, the models invoke Right of Publicity claims under New York law, which prohibits the “use for advertising purposes, or for the purpose of trade, the name, portrait or picture of any living person without first having obtained the written consent of such person.”

“These claims are, of course, what this lawsuit is all about,” the court states, but not without issue, as “it is absolutely and indisputably the case that an individual who does not reside in New York cannot bring a claim under New York’s Right of Publicity Law.” The problem here, according to the court, and the reason that many of the models’ “Right of Publicity claims must be dismissed” is because “the majority [of them] are not New York domiciliaries and so, [they] enjoy no protection under New York’s Right of Publicity Law.”

With that in mind, the court ultimately dismisses most of the models’ Right of Publicity claims, including the 18 non-resident plaintiffs who argued that their business ties to New York should be considered as a sufficient basis for maintaining their state law claims. Unpersuaded, the court stated that “the mere fact that a majority of their modeling work takes place in New York is not sufficient to establish domicile, when the plaintiffs reside elsewhere.” As such, the court left in place the Right of Publicity claims of just 17 of the models who are residents of the state of New York against Moda, which has not moved to dismiss the right of publicity claims of those plaintiffs. As for Conde Nast, it asked the court to decline to exercise supplemental jurisdiction over these purely state law claims, which the court refused due to the various claims that are still in place against Moda.

The case is Champion et al., v. Moda Operandi, Advance Publications d/b/a/ Conde Nast, 1:20-cv-07255 (SDNY).