Rebranding has been on the rise in the wake of the pandemic. Companies are looking to reflect changes in their operations, including expanded e-commerce capabilities, and tap into rising consumer attention to – and generate a competitive advantage from – environmental, social, and governance issues by promoting themselves and their goods/services as climate-friendly. Surveying 600 business owners and brand marketing experts across the U.S. and Canada last year, Chicago-based marketing consultancy UpCity found that 51 percent of businesses have changed their branding strategy since the COVID-19 pandemic, with many respondents stating that “revising or changing actual branding assets and visuals, as well as the language used to describe [their] brands” has been a priority in the post-pandemic landscape.

More than merely making changes to company branding and messaging, UpCity determined that the majority of survey respondents were also concerned about “enhancing or modifying” the platforms they are using – their websites, social media channels, etc. – and/or “the types of products and services” they are offering up. The pandemic forced “a major pivot for many brands to expand the products or services available in order to attract a broader spectrum of customers,” UpCity said. At the same time, the enduring impact of the pandemic also pushed many brands to embrace e-commerce (and digital platforms more broadly) in order to “fulfill orders and meet customer needs,” and expand the scope of their operations to reach “ideal new customers that have emerged.”

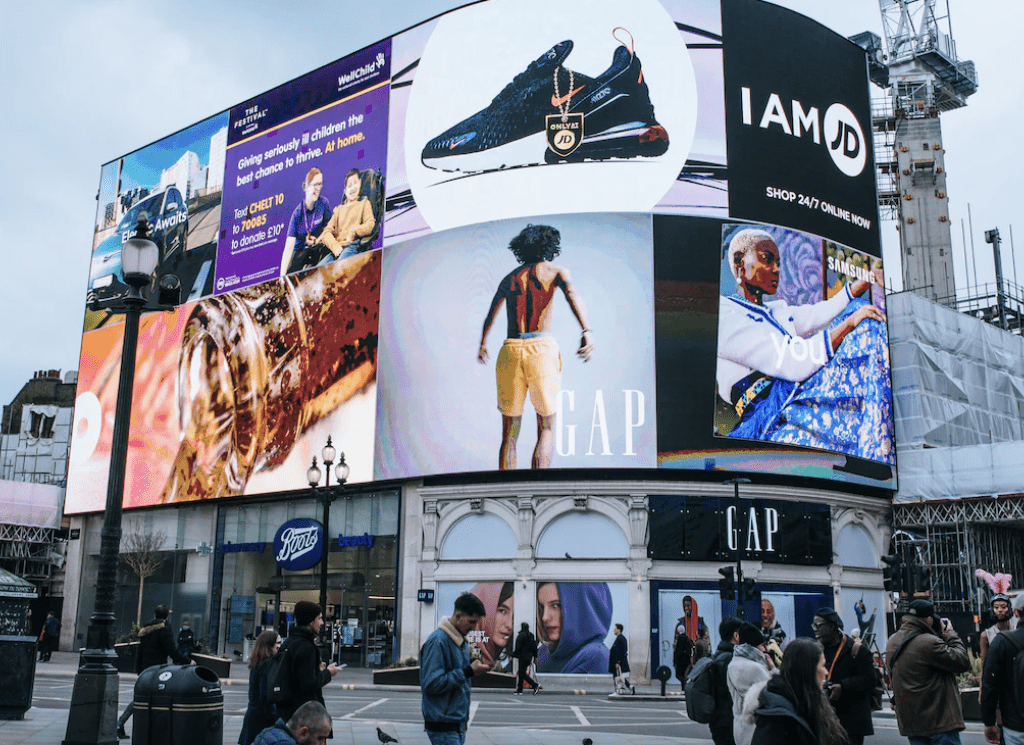

As a result, UpCity stated that amid “a massive restructuring and shift” in terms of how companies “serve their customers and clients, and the types of products and services on offer,” many have “reimagine[d] their branding and marketing” in order to: (1) “recover or retain client relationships and capture the attention of potentially previously untapped client segments who now fall within their target audience,” and (2) ensure that their branding assets are uniform across online platforms. (The push to adopt uniform branding across an array of mediums – from ad campaigns in print media to branding at the heart of companies’ social media accounts – has been underway since before the pandemic, of course, as reflected in the blanding phenomenon. This trend could now be in the process of reversing to some extent, with some brands – like Burberry – re-adopting earlier versions of their logos and/or stylized word marks that are not devoid of serifs.)

Dropping Vowels

Another “interesting dynamic in play” among the survey respondents in the realm of rebranding (or in many cases, sub-branding), per UpCity, is the number of companies that have “leaned heavily on using made-up words and/or acronyms as a short-hand for communicating about what a brand does, what it’s about, and often as a way to stand out in the crowded economic landscape.” While more than half (53 percent) of respondents “currently have a brand name comprised of made-up words and/or acronyms,” UpCity cautioned that “there are significant disadvantages to this approach, as customers could misconstrue what an acronym might stand for or lose the thread of your branding and forget your company name if you use nonsense words or phrases rather than a naturally occurring set of words, but instead made-up words with no intrinsic meaning.”

Not an entirely novel approach, we previously addressed the rate at which companies – from Vetements to British asset manager Standard Life Aberdeen – have been dropping vowels from their names in order to fashion new branding and reap new benefits. By adopting these arguably distinctive monikers, brands may be able achieve a few things: For one thing, they potentially stand to avoid running into confusingly similar trademarks that are already in use, which would likely prevent them from amassing trademark rights of their own. At the same time, and in an even more practical sense, the adoption of unused names – no matter how unconventional – provides new brands with the chance to secure the valuable social media handles and domain names of their choice, which might otherwise be difficult (or expensive) to obtain since so many of these assets have, in fact, already been claimed.

Maybe more compelling, though, is the fact that this type of rebranding may enable companies to register versions of marks that would otherwise be rejected by trademark offices. While Vetements, for instance, has successfully amassed registrations for its name across an array of goods/services, it has been unable to register it for use on apparel/clothing and corresponding retail services. (In fact, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“TTAB”) is expected to issue a final decision in a reconsideration proceeding over the registrability of VETEMENTS for use in Classes 25 and 35, following denials based on the doctrine of foreign equivalents. More about that here.)

Despite the difficulty that it has experienced when it comes to the VETEMENTS word mark, the fashion company has been able to register VTMNTS – the name of a separate brand the company launched in 2021 – with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Officefor use on clothing and clothing-centric retail services.

The same might prove to be true for Nike, which is currently awaiting a decision from the TTAB in a matter over two trademark applications for SNKRS for use in connection with an online marketplace featuring footwear and clothing, among other things. Given that USPTO examiners refused to register the mark on the basis that SNKRS is “generic,” or alternatively, is “merely descriptive and has not acquired distinctiveness in connection with Nike’s services,” it is safe to say that Nike would have no luck if it were to try to register the word “sneakers” in any relevant classes of goods/services. (Note: It has not attempted to do so). By dropping the vowels to fashion a slightly less straightforward take on the word sneakers and citing widespread use of the app and consumer survey evidence that shows that 62 percent of respondents “identified SNKRS as a brand name,” Nike may be able to nab registrations.

As for a company that has had success in registering a vowel-less mark, Chanel comes to mind, with the brand amassing a trademark registration in the U.S. for CHNL for use on footwear back in 2020.