MSCHF is looking to put a swift stop to the lawsuit waged against it for allegedly infringing a streetwear brand’s trademark by way of its headline-making Wavy Baby sneakers. In an April 16 pre-motion conference request addressed to Judge Rachel Kovner, counsel for MSCHF states that the lawsuit that Plaintiff WaveyBaby Holdings filed in a New York federal court late last month is “doomed” given that MSCHF’s use of the “Wavy Baby” name amounts to descriptive fair use, is protected by the First Amendment, and does not create a likelihood of confusion with WaveyBaby. And still yet, in addition to these “immediate failings,” MSCHF asserts that “discovery would establish that [WaveyBaby] does not possess a valid trademark registration because (among other reasons) many others preceded [its] use of the name to sell clothes.”

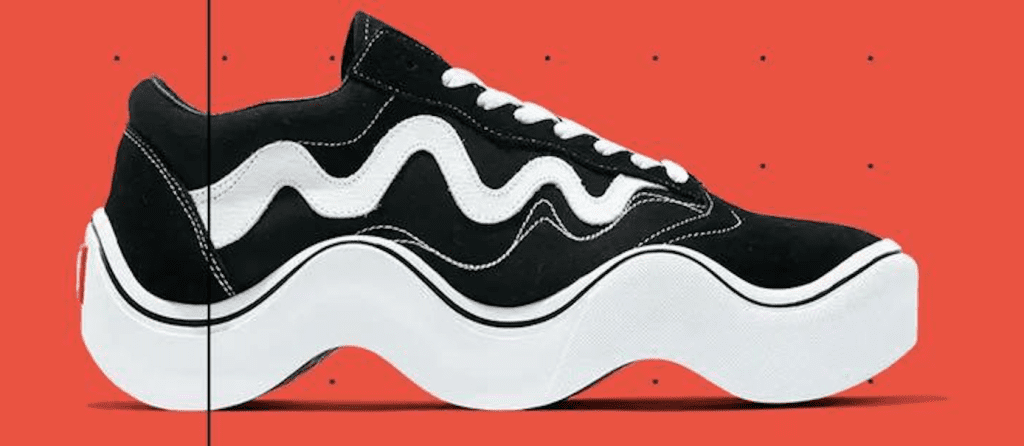

Setting the stage in the request, MSCHF states that it is “an American art collective whose art projects, exhibited at the most renowned art galleries and venues, critique and comment upon American culture.” In line with its pattern of critiquing/commenting on consumer culture, MSCHF maintains that it created a “wildly distorted evocation of Vans’ iconic skate shoe, Old Skool” in furtherance of “a commentary on the Old Skool’s fall from grace as a symbol of west-coast skateboard culture to a paragon of mass-consumerism.”

Against that background, MSCHF – which released the sneaker in April 2022 alongside rapper Tyga – claims that descriptive fair use is a complete defense here, as the complaint and referenced documents “demonstrate that our titled use of Wavy Baby is use (a) other than as a mark, (b) in good faith, and (c) to describe characteristics of our artwork.” Specifically, MSCHF argues that “the title of a creative artwork (such as Wavy Baby) that is not part of a series is not a trademark use,” as “without such a series, no continued use in commerce exists – a necessary component of trademark use.”

In addition to choosing the “Wavy Baby” name in good faith (“the name is relevant to our artwork”), MSCHF states that the “descriptive title stands in service of our critique of the Old Skool’s symbolism.” (The “term ‘wavy’ describes shape and taps into the use of ‘wavy’ as slang for something stylish and fresh – the antithesis of Vans’ Old Skool.”)

Turning to its First Amendment argument, MSCHF contends that WaveyBaby’s complaint warrants dismissal under Rogers v. Grimaldi, which protects trademark uses that are: (1) artistically relevant and (2) not explicitly misleading as to the source of the expression. “Both characteristics are clear from the face of the complaint,” per MSCHF, which claims that it “deploy[ed] Wavy Baby as the title of an expressive piece – to underscore commentary on Vans’ Old Skool, thus making our use artistically relevant to its expression.” As for the second prong, MSCHF says that it does not use Wavy Baby “to identify the source of that piece (i.e.,MSCHF), and certainly do[es] not use the term in a manner that ranks as an ‘explicitly misleading’ attempt to deem WaveyBaby Holdings LLC (rather than MSCHF) as the source of the artwork.”

MSCHF notes that the test from Rogers “protects our title usage, even while broader application of the test undergoes review in the U.S. Supreme Court.”

Finally, MSCHF asserts that WaveyBaby does not even try to establish that likelihood of confusion under the Polaroid factors. Arguing against a potential confusion claim, MSCHF states that other companies maintain over twenty registrations for word “Wavy” in Class 25, meaning that any trademark rights that WaveyBaby has in its name “are narrow and do not reach MSCHF.” In case that is not enough, MSCHF says that the uses of the “marks” are not similar: “Unlike WaveyBaby LLC, we never put the title of our piece on the ‘shoe;’ instead, we use a mark with the word ‘Wavy.’”

MSCHF also notes that the complaint “contains no allegation that the title Wavy Baby, let alone the Plaintiff’s mark (WaveyBaby), appears anywhere on the piece. Instead, the shoe contains three uses of the word Wavy (all without an ‘e’): on the bottom (in a parody of a legal disclaimer); inside (as critique of trademark practices); on the heel (as part of the shoe’s logo).”

An additional note: Timing is an interesting element here. The WaveyBaby lawsuit was not only filed one year after MSCHF first released the sneakers (for a point of reference, Vans filed its trademark suit against MSCHF over the Wavy Baby sneakers on April 15, 2022, ahead of the formal release of the allegedly infringing sneakers on April 18), the filing also comes almost one year after the district court entered an injunction in the Vans v. MSCHF case. In an April 29, 2022 decision and order, the court barred MSCHF from marketing, offering up, and selling the Wavy Baby sneakers for the duration of the Vans case. As such, WaveyBaby’s case is not only striking from a timing perspective, but it also raises some questions from a remedies POV since WaveyBaby is seeking injunctive relief to bar MSCHF from “advertising, marketing, promoting, offering for sale, distributing, or selling the infringing Wavy Baby shoes.”

Also worthy of note is the fact that WaveyBaby asserted in its complaint that it “sent a cease-and-desist letter to MSCHF via its counsel on or about April 12, 2022,” which seemed to suggest (to me) that its delay in filing suit could have been the result of failed discussions between the parties to resolve the matter. However, MSCHF states in a footnote in its letter to the court that “contrary to the allegations, MSCHF never received a cease and desist letter. Instead, prior counsel addressed invited discussion.”

With the foregoing in mind, MSCHF tells the court that WaveyBaby’s complaint warrants treatment on Rule 12 motion.

The case is WaveyBaby Holdings, LLC v. MSCHF Product Studio Inc, et al., 1:23-cv-02486 (EDNY).