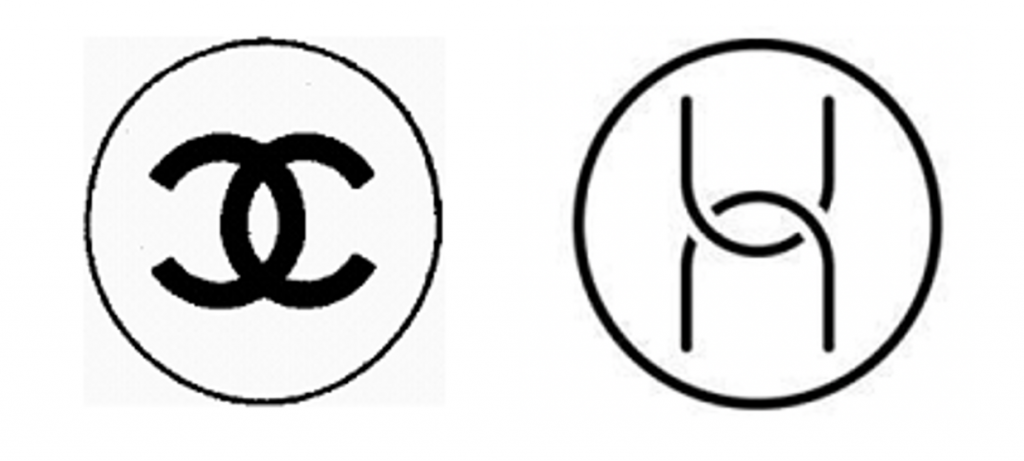

Typically the subject of trade secret misappropriation and “forced technology transfer” headlines in connection with allegations lodged against it by the U.S. government, Huawei has also been embroiled in another matter over the past several years, a trademark case waged against it by … a luxury fashion brand. The Chinese tech behemoth has been facing off against Chanel, with the French fashion house seeking to block Huawei’s quest to register a trademark with the European Union Intellectual Property Office (“EUIPO”) for use on computer hardware and software programs on the basis that the mark is too similar to its famed double “C” logo. In a decision on Wednesday, a panel of judges for EU General Court sided with Huawei in the nearly 4-year-old matter, holding that since the respective parties’ marks “must be compared as applied for and registered, without altering their orientation, the figurative marks at issue are not similar.”

The trademark squabble got its start in December 2017 when Chanel initiated an opposition proceeding with the EUIPO in order to block the impending registration of Huawei’s logo. In its opposition, Chanel pointed to its registration for a logo that consists of interlocking C’s for use on goods in Class 9 (namely, “cameras, sunglasses, glasses; earphones and headphones; computer hardware”), which is the same class that Huawei is looking to register its logo, and argued that Huawei’s mark is confusingly similar. Beyond that, Chanel also pointed to the registration that it has maintained in France since the mid-1980s, for the same double “C” logo – albeit, this time with the circle – for use “in Classes 3, 14, 18 and 25,” including “perfumes, cosmetics, costume jewellery, leather goods, [and] clothes.’” With that longstanding registration in mind, Chanel argued that if the EUIPO allows for the registration of Huawei’s mark, it would enable the Chinese giant to inappropriately piggyback on the fame of Chanel’s mark.

The matter has resulted in a string of losses for Chanel. Following a defeat before the EUIPO’s Opposition Division in early 2019, Chanel appealed to the Fourth Board of Appeal of EUIPO, which also dismissed the appeal. In a decision in November 2019, the Board of Appeal stated that “from a visual point of view the marks had a different structure and were composed of different elements,” asserting that “the mere presence, in each of the marks at issue, of two elements that are connected to each other does not render the marks similar even though they share the basic geometric shape of a circle surrounding those elements.” The court went on to find that that there was no likelihood of confusion on the part of the relevant public in connection with the two companies’ trademarks, in large part because Huawei’s mark is “different from [Chanel’s] allegedly reputed mark.”

With yet another loss in hand, Chanel appealed again, this time to the EU General Court, arguing, among other things, that “from a visual point of view, the comparison of [its mark and Huawei’s] mark, in the orientation in which they were applied for, does not exclude certain similarities, so that those marks may be regarded as displaying similarities.” According to Chanel, “when [Huawei’s] mark is rotated by 90 degrees,” it is “at the very least, visually similar to an average degree” to Chanel’s existing mark. “From a phonetic point of view,” Chanel asserted that the Board of Appeal “was right to find that a phonetic comparison of the marks at issue was impossible, since they could not be pronounced.” However, from “a conceptual point of view,” Chanel argued that the Board of Appeal erred in finding that the marks are dissimilar. Chanel contended that “since the signs have no meaning and do not convey any concept, the Board of Appeal should have found that there was no need to carry out a conceptual comparison.”

In the latest round, the General Court held in its April 21 decision that the marks at issue do, in fact, “share certain characteristics, namely a black circle, two interlaced curves, which the circle surrounds, also black, intersecting in an inverted mirror image, and a central ellipse, resulting from the intersection of the curves.” Despite such similarities, however, the court listed a slew of reasons why “the marks at issue are visually different” – from “the more rounded shape of the curves” to the “greater thickness of the line of those curves in [Chanel’s] mark as compared with the line of the curves in [Huawei’s] mark.”

With a lack of visual similarity in mind and no need to do an analysis of phonetic similarity (since the marks are logos and not work marks), the court considered the issue of conceptual similarity, stating that “it should be noted that [Huawei’s] mark and [Chanel’s] mark are composed of a circle containing an image referring to stylized letters.” Citing the Board of Appeal’s finding that “the mere fact that they have the geometric shape of a circle cannot make them conceptually similar,” the court further held that “although the initials of the founder of [Chanel] should be detected in the image referring to the stylized letters of the [Chanel] mark, it is the stylized letter ‘h’ or the two interlaced letters ‘u’ that could be perceived in the image referring to a stylized letter of the [Huawei’s] mark, so that the marks at issue are conceptually different.”

With the foregoing in mind, the court held that “the Board of Appeal was correct in finding that the marks were dissimilar overall and that, accordingly, the opposition had to be rejected,” noting that “in so far as the signs at issue are not similar, the other relevant factors for the global assessment of the likelihood of confusion cannot under any circumstances offset and make up for that dissimilarity and therefore there is no need to examine them.” As such, the court shot down Chanel’s Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation No 207/2009 and Article 8(5) of Regulation No 207/2009 arguments, and paved the way for Huawei’s mark may proceed in the registration process with the EUIPO, assuming, of course, that Chanel does not appeal to the Court of Justice. Chances are, Chanel very well might try its hand one last time before the EU’s highest court.

Trademarks but also Trade Secrets

Reflecting on the latest round of the case, EU trademark and copyright attorney Eleonora Rosati told TFL that the decision “marks a welcome, yet (thankfully) unsurprising confirmation that, in line with case law and the EUIPO Guidelines, any comparison between signs in the context of opposition proceedings is to be conducted by having regard to the form in which they are protected – or in other words, the form in which they are registered or applied for.” As such, “the actual or possible use in another form is irrelevant.”

In its report on the case on Tuesday, Reuters stated that the “trademark spat underlines how luxury brands jealously guard their signature logos and trademarks that often symbolize luxury, style and exclusivity to millions of people worldwide.” An overarching dependence on qualities of exclusivity and scarcity by players in the luxury and high fashion segment, qualities that are often-time created by heritage-centric story-telling and driven home by way of large-scale marketing initiatives, helps to explain why brands, such as Chanel, are eager to police unauthorized uses of their wildly valuable trademarks and/or marks that are “confusingly” similar to their marks.

As Chanel recently stated in a lawsuit that it filed against an unauthorized reseller, the “luxury, exclusivity and prestige associated with Chanel’s products” – and maybe more precisely, the trademarks that appear on its products and the goodwill associated with those marks – “form an integral part of the CHANEL brand, and of its promise and attraction to consumers and potential consumers.”

At the same time, the case is striking given the tensions between the U.S. government and Huawei. The 34-year-old tech company has served as the poster child of the Trump administration’s war on Chinese “intellectual property theft,” with Huawei – which holds the title of the world’s largest telecommunications equipment manufacturer – and two of its U.S. subsidiaries being charged by the Department of Justice in February 2020 with conspiracy to “steal trade secrets stemming from the China-based company’s alleged long-running practice of using fraud and deception to misappropriate sophisticated technology from U.S. counterparts,” and thereby, running afoul of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act.

In a February 13, 2020 release, the DOJ asserted that the charges “relate to the alleged decades-long efforts by Huawei, and several of its subsidiaries, both in the U.S. and in the People’s Republic of China, to misappropriate intellectual property, including from six U.S. technology companies, in an effort to grow and operate Huawei’s business. ” The allegedly “misappropriated intellectual property included trade secret information and copyrighted works, such as source code and user manuals for internet routers, antenna technology and robot testing technology.”

The 16-count indictment followed from a “bold” May 2019 move by the U.S. to blacklist Huawei and other Chinese firms from buying components from U.S. companies without U.S. government approval in order to “prevent American technology from being used by foreign-owned entities in ways that potentially undermine US national security or foreign policy interests,” according to the Trump administration. By adding Huawei and 70 of its affiliates to the U.S. Commerce Department’s “entity list,” the government made “it difficult – if not impossible – for the firm to sell certain products,” per AlJazeera, citing its “reliance on U.S. suppliers.”

Fast forward to August 2020 and additional regulations were enacted amid an escalating trade war, barring the U.S. government from buying goods or services from any company that uses products from five Chinese companies, including Huawei.

The case is Chanel v EUIPO – Huawei Technologies, T-44/20.