Court proceedings in the case that Chanel filed against The RealReal may be temporarily on hold as the parties have agreed to mediation in their counterfeiting and antitrust fight, but the case that the famed fashion house waged against What Goes Around Comes Around (“WGACA”) in March 2018 is very much underway in court, with both parties filing motions for summary judgment this week in respective attempts to land an early victory in the 3-year-old case, in which Chanel is accusing luxury reseller WGACA of false advertising and trademark infringement/counterfeiting in connection with its marketing and sale of pre-owned Chanel goods.

WGACA’s Motion

Setting the stage in its July 26 filing, WGACA asserts that at “the heart of the instant action is Chanel’s attempt, through the courts, to control the secondary/resale market by attacking a reseller of its goods with multiple and unfounded claims which Chanel continues to press despite the absence of a factual basis.” Chanel lacks any facts “to support it spurious claims,” WGACA argues, and urges the court that “the time has come for Chanel’s abusive and bad faith prosecution of WGACA to come to an end.”

Specifically, counsel for WGACA argues that the court should toss out Chanel’s claims on the basis that the French fashion giant cannot: (1) prove that it suffered any damages as a result of WGACA’s alleged false advertising and false association endorsement/unfair competition; (2) establish its trademark infringement and counterfeiting claims; and (3) make its case for claiming that WGACA also violated New York’s General Business La, which prohibits companies from engaging in “deceptive acts or practices in the conduct of any business.”

On the first point, WGACA claims that in order to make viable false advertising and unfair competition claims, Chanel must show, among other things, that it suffered “an injury to a commercial interest in reputation or sales.” Aside from counsel for Chanel claiming that WGACA’s activity was “harming the [Chanel] brand,” WGACA argues that Chanel failed to provide “any information to suggest that Chanel has actually, in fact, lost any money.” As such, WGACA argues that Chanel’s false advertising claims are “fatally defective,” and should be dismissed.

Chanel also fails on the counterfeiting and trademark infringement front, per WGACA. Primarily, WGACA argues that Chanel has no evidence that the 12 allegedly counterfeit bags that it sold – which Chanel says have “serial numbers purportedly stolen from a Chanel factory” – were not manufactured by a Chanel factory. Instead, the defendant claims that Chanel only has evidence “that the serial numbers of the Chanel authenticity cards for these bags were among the 30,000 stolen from one of Chanel’s factories, Renato Corti S.p.A., in 2012.” Beyond that, WGACA asserts that “by Chanel’s own admission, if an item is counterfeit, it has to have non-genuine/fake hardware and Chanel would be able to determine such from an inspection.”

Yet, when two of those 12 bags were examined by a Chanel expert, WGACA claims that the expert “could not identify any specific issue with either bag,” and also failed “to identify non genuine hardware on the accused counterfeit items it inspected,” which it argues is “conclusive proof that the items are not counterfeit.”

As for the 51 bags that Chanel alleges that WGACA sold that were “infringing” because they were not “subject to Chanel’s quality control review” before they were initially released into the market, WGACA argues that this claim also fails, as Chanel not only has “no evidence that the subject bags were not manufactured by authorized factories,” but the brand “implicitly acknowledges that they were.” In case that is not enough, WGACA argues that Chanel essentially waited too long to bring its infringement claim (i.e, waited longer than the applicable six-year statute of limitations), and that even “if there is any infringement, there clearly was no wrongdoing by WGACA” because it had “no knowledge of the missing ‘quality control’ data points,” which means that “WGACA’s sales of these items would not trigger any equitable basis to force WGACA to give up the profits from those sales.”

WGACA goes on to also argue that “beyond the claims as to the alleged counterfeits and the 51 [allegedly infringing bags] that do not appear in [Chanel’s] data base, Chanel’s infringement claims are also barred by the doctrine of nominative fair use, [as] all of the instances cited by Chanel wherein ‘Chanel’ is used is fair use because WGACA uses Chanel trademarks to identify goods that WGACA is lawfully permitted to sell.” Significantly, WGACA claims that Chanel has “proffered no evidence that any of WGACA’s ads has or is likely to cause consumer confusion.”

And finally, WGACA asserts that Chanel fails to make its New York General Business Law (“GBL”) claim because a “non-consumer, such as Chanel, must demonstrate that the alleged conduct has significant ramifications for the public at large.” Chanel fails in this regard, per WGACA, because “the public at large is not affected [by WGACA’s alleged actions], [as] only Chanel and perhaps, at best, the select group who may purchase the items” have been impacted. Since “consumer confusion is not enough to support a claim under the GBL in the absence of harm to the public or safety,” WGACA argues that Chanel’s GBL claim should be dismissed.

Chanel’s Motion

In its own filing on July 26, a motion for partial summary judgment, Chanel is seeking a pre-trial judgment from the court on its false association/false advertising and trademark infringement claims, as it asserts that the facts underlying its claims are not in dispute, and thus, the court – as opposed to a jury – can decide on the causes of action.

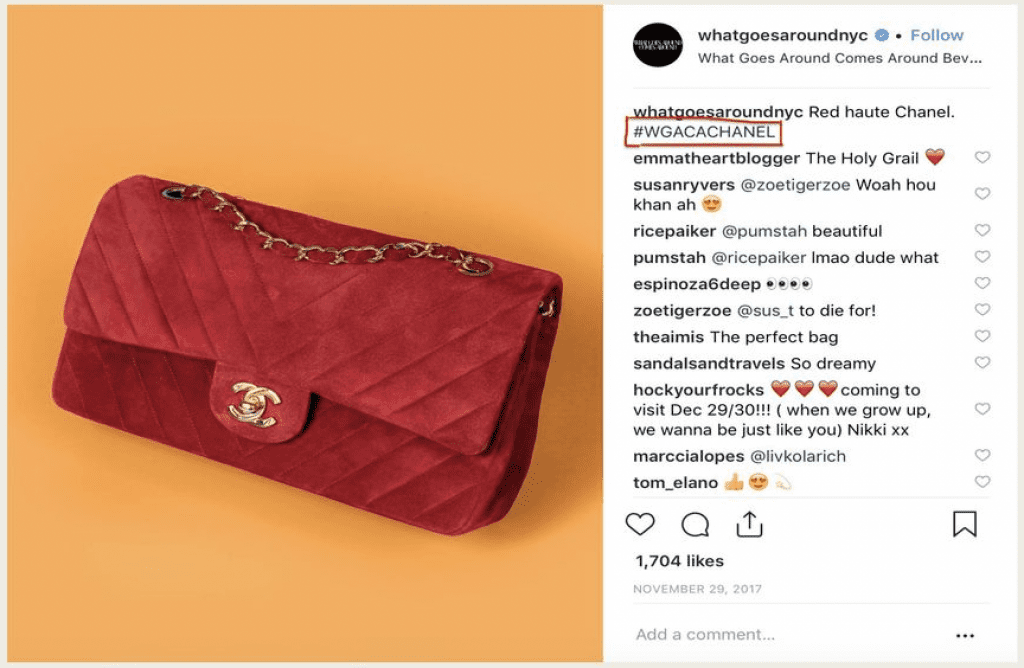

As the basis for its false association/false advertising claims, Chanel argues that WGACA has “willfully trad[ed] on [its] well-known trademarks, including using Chanel’s trademarks, quotes, and images of [its] founder Coco Chanel, hashtags with [its] trademarks (including egregiously #WGACACHANEL), pictures of Chanel runway shows and prior Chanel advertisements to draw a false association with Chanel, as well as WGACA’s falsely guaranteeing that every Chanel item it sells is authentic.”

In terms of its trademark infringement claim, Chanel asserts that “WGACA’s sale of CHANEL-branded items that are not genuine, not made by Chanel, not inspected and approved for meeting Chanel’s specifications, and not authorized for sale or sold by Chanel,” paired with the “actual confusion [it caused] amongst consumers” as a result, runs afoul of the law.

Arguing for summary judgment, Chanel states that in order to prevail on a trademark infringement or false association claim, a plaintiff must establish that: (1) the plaintiff owns a mark entitled to protection, and (2) the defendant uses a similar mark in commerce in a way that is likely to cause confusion among the relevant consuming public. Looking beyond its famous and incontestable marks, Chanel asserts that WGACA is, in fact, using making “unnecessary, extensive, and prominent use of the CHANEL marks across its advertising channels,” in a way that is likely to – and actually has caused confusion, as “the products [it is offering up] are identical, and that the secondhand and direct luxury goods markets [are] complimentary” to one another.

Speaking to the likelihood of confusion, Chanel claims that in addition to “multiple consumers call[ing] or email[ing] Chanel’s customer service hotline demonstrating confusion as to the association between Chanel and WGACA,” it found via a survey that consumers are likely to be confused about the “source, sponsorship, affiliation, connection, or identification” of WGACA’s products.

In particular, Chanel states that “a consumer survey found that after viewing WGACA’s website, a majority of survey participants believed that: (1) Chanel approved the sale of WGACA’s CHANEL-branded goods (61 percent); (2) Chanel sponsored WGACA’s sale of CHANEL- branded goods (47 percent); (3) Chanel is associated with WGACA (47 percent); and (4) WGACA was either an affiliate, partner, collaborator, or authorized reseller of Chanel (73 percent).”

Chanel also points to a number of other factors that weigh in its favor, including WGACA’s alleged practice of “repair[ing], refurbish[ing], and re-dy[ing] its CHANEL-branded products prior to sale,” but failing to “disclose such repairs to consumers,” causing Chanel’s “reputation [to be] clearly harmed” by WGACA’s activities. Moreover, Chanel argues that WGACA’s alleged infringement was intentional and a way “to get a free ride upon the reputation of a well-known mark.” Since at least June 2015 when Chanel sent WGACA a cease and desist letter putting it on notice of its advertisement of an inauthentic Chanel bag, the fashion brand claims that WGACA has, nonetheless, “used its advertisements to create a false association with Chanel in order to capitalize on Chanel’s reputation and goodwill, with full knowledge that Chanel objected.”

As such, Chanel argues that summary judgment is appropriate on its trademark infringement and false advertising claims, also asserting that its “reputation is clearly harmed” by WGACA’s activities.

Turning its attention to WGACA’s affirmative defenses of waiver, laches, estoppel, acquiescence, consent, fair use, and the first sale doctrine, Chanel claims that the reseller falls short on each of them.

For one thing, Chanel argues that nominative fair use is off the table, as WGACAChanel-branded items are not only “readily identifiable without the multiple unauthorized uses of the Chanel marks that WGACA engaged in, including the ‘hashtag’ #WGACACHANEL,” Chanel argues that WGACA uses the Chanel marks “more than is necessary to identify it as a reseller of purported Chanel-branded items.” For instance, it claims that WGACA has by used its trademarks “to advertise its business generally and to advertise a general sale on all its products, and displaying the Chanel marks more prominently than the WGACA trademark (and in the same stylized font at the WGACA trademark).”

In doing so, Chanel claims that WGACA “crosses the line from identifying WGACA as a reseller of purported Chanel-branded goods to falsely suggesting an association between Chanel and [itself],” and thus, WGACA “cannot shield its inherently confusing advertisements by resorting to the nominative fair use defense.”

When it comes to WGACA’s first sale doctrine defense, Chanel also calls foul, citing the court’s earlier assertion that the first sale doctrine “applies only where a ‘purchaser resells a trademarked article under the producer’s trademark, and nothing more.” In the case at hand, WGACA’s actions “go well beyond merely reselling Chanel-branded products,” the brand claims, and “are consistent with creating a false association between WGACA and Chanel.”

Beyond that, Chanel argues that there was not authorized first sale of at least some of the bags at issue, namely, the ones that Chanel argues are counterfeit or otherwise infringing. “It is undisputed that Chanel did not authorize the first sale of these items,” and thus, the goods cannot be considered genuine as a matter of law and infringement is established,” Chanel argues. And even if WGACA could show there was a qualifying “first sale,” which Chanel says it cannot do, in order to rely on a first sale defense “WGACA must also establish that ‘the goods which were later resold without authorization were genuine,’” which, again, Chanel argues that WGACA cannot do.

With the foregoing – and an array of other arguments – in mind, counsel for Chanel argues that its motion for summary judgment should be granted in its entirety.

THE BROAD VIEW: The latest developments in the case come as carefully-managed fashion and luxury goods entities – and even sportswear brands – continue to demonstrate their clashes with resale and specifically, the relative lack of control that they have over certain marketing and sales situations as a result of the rise of the burgeoning secondary market. Earlier this month, for instance, Nike filed two trademark lawsuits against customizers, with the Beaverton, Oregon-based giant specifically pointing to the potential for “confusion in the secondary sneaker markets.”

The case is Chanel, Inc. v. What Goes Around Comes Around, LLC, et al., 1:18-cv-02253 (SDNY).